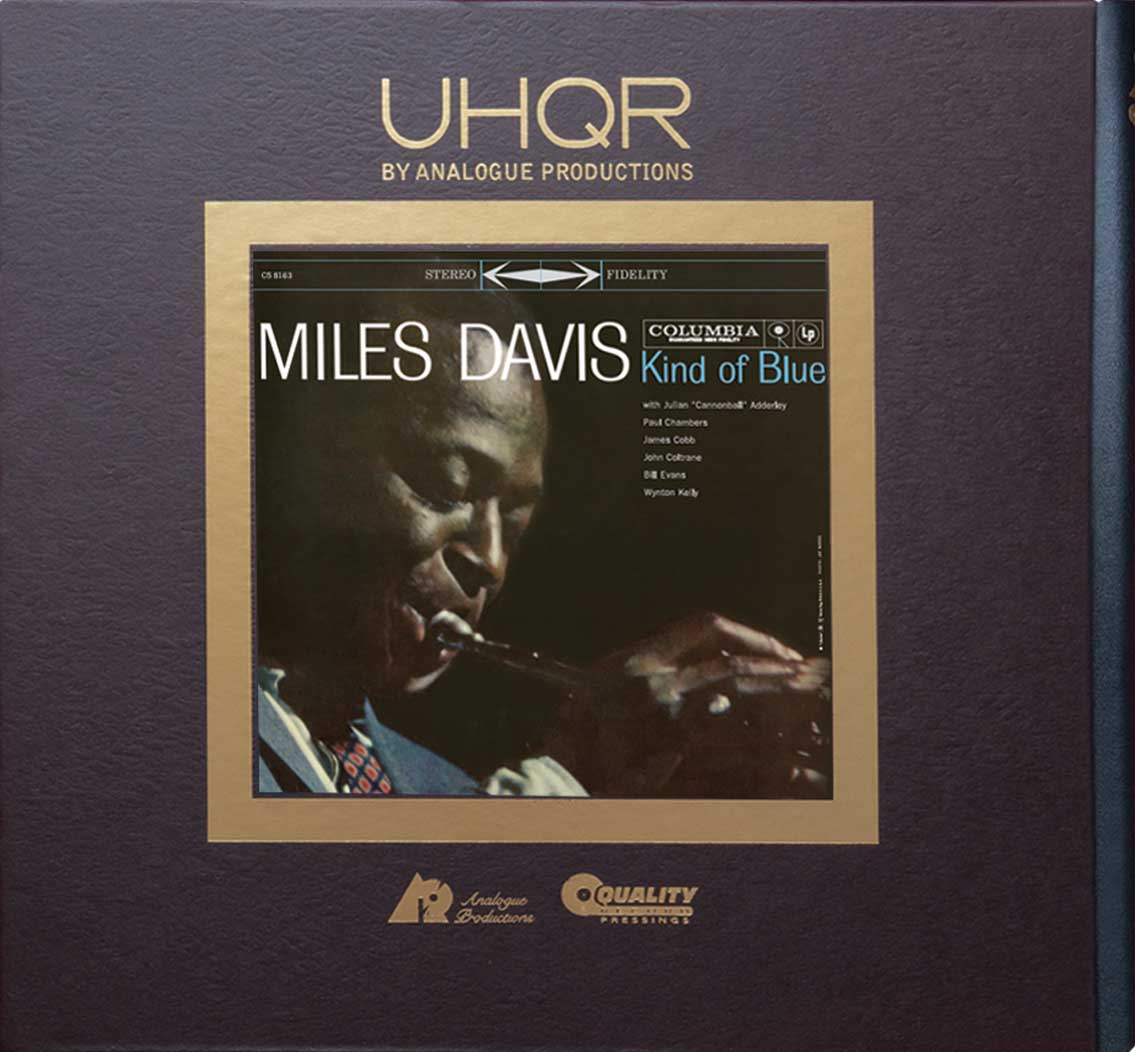

The Latest (and Last) "Kind of Blue"

The best-ever pressing of the best jazz album

(Revised Sept 17, 2022)

Yes, yes, I know what you’re thinking: “What’s this now, another audiophile reissue of Kind of fu*king Blue?!” But here’s the thing: not only is this new one—pressed by Acoustic Sounds at 45rpm across two slabs of 200-gram UHQR Clarity vinyl—the best of the bunch; there almost certainly won’t be a better one for the foreseeable future.

Not much need be said at this point about the 1959 Miles Davis classic: the best-selling jazz album of all time; by some accounts (including mine, on most days) the best jazz album, period; an artistic breakthrough that’s also completely accessible, a rarity in any medium. It was the culmination of Miles’ experiments in modal jazz, which was structured not on precise bars and chord changes but on scales that could be stretched out as the mood suited. These are improvisations—Miles came into the studio with a few lines of scales for each tune and asked his band to play variations on them—yet they sound like perfect through-compositions.

It was also the only studio album made by Miles’ sextet at the time—John Coltrane on tenor sax, Cannonball Adderley on alto, Bill Evans on piano (with Wynton Kelly subbing on one track), Paul Chambers on bass, and Jimmy Cobb on drums. Coltrane, whose “sheets of sound” had torn through chords on top of chords within chords, eased into this new stream as lithe and lyrical as ever. Adderley, who sounded like Parker with a gospel vibrato, delves into the feeling of the blues. Evans, whose Ravelian touches had always slipped around chords, rather than pounding them directly, fit in perfectly. Chambers and Cobb supplied their supple anchors. And Miles, freed from Parker’s grip, uncoiled his most limber, graceful solos yet—haunting, soothing, gorgeous, yet gleaning with a knife-sharp edge.

It is also a superb sounding album, recorded at Columbia’s 30th Street Studio by the great Fred Plaut, who would be as famous as Rudy Van Gelder if the label had printed technical credits on the back of its albums.

But why another reissue now, and what makes it so special? A little history. In the mid-1990s, Mike Hobson’s Classic Records put out a slew of limited-edition Kind of Blue LPs, all mastered by Bernie Grundman from the original three-track analog tapes: on 180-gram vinyl, then 200-gram vinyl, then a double album that included an alternate version of “Flamenco Sketches” (the only one on the album, as all the other tracks were unedited first takes). All of these releases were revelations, as Columbia’s own vinyl and CD reissues over the previous 30 years sounded pretty lifeless. Then came Hobson’s obsessive-compulsive coup de grace: a four-disc set of LPs, grooves stamped at 45rpm on one side, blank on the other (to minimize resonances between the record’s bottom surface and the turntable’s platter). This extremely limited-edition box sounded best of all, very close in quality to Columbia’s six-eyes first pressing.

Over the next decade, a few other companies tried their hand at reissues—including a noisy blue-vinyl LP from Sony/Columbia and a Mobile Fidelity 45rpm with too much boom in the base—but none of them touched any of the Classics.

Then, in August 2021, Chad Kassem’s Analogue Productions entered the ring. When Classic went out of business long ago, Kassem bought its assets, including Grundman’s Kind of Blue masters. He renewed the license, created new plates, and pressed new records by hand, one at a time, on a heavily modified, temperature-controlled Finebilt press.

And it turned out to the best the best-sounding Kind of Blue ever, better than even the original. As I wrote in Stereophile at the time:

[T]here are fine touches in [Jimmy] Cobb’s snare swooshes and cymbal taps—accents on accents, rhythms within rhythms—that I’ve never heard before. [Paul] Chambers’ bass lines are stunningly clear: the notes he’s playing, the pluck of the strings, the glow of the wood. There are also new layers of detail in Miles’ mouthpiece manipulations, [Bill] Evans’ pedal work, and the sheer beauty of [John] Coltrane’s and [Cannonball] Adderley’s saxophones.

That was a year ago. All 25,000 copies quickly sold out. Kassem’s new edition—also stamped in an edition of 25,000—is from the same master, pressed on the same type of vinyl, packed in the same fancy box. The only difference is that the music is on two LPs, cut at 45rpm, meaning the grooves are much wider. All things equal, this should make for finer detail, an airier ambience, more lifelike sound generally.

And that’s what you get here. Take the passage from my Stereophile review and step it up a few notches: “finer touches…even more stunningly clear…still more layers…the ecstatic beauty…” Everything is more present, more brassy, woody, or metallic, depending on the instrument. There’s a more palpable sense of a human being blowing through a mouthpiece, plucking a string, coaxing a keyboard, or tapping a snare drum.

In short, take any account you’ve read—or any memory you treasure—of this album’s sonic glories, and embellish every admiring adjective with more, more, better, better.