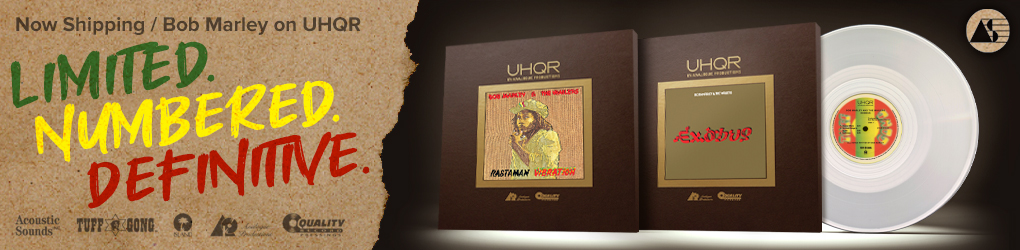

Steely Dan's Controversial 'Katy Lied' Gets the Analogue Productions UHQR Treatment

tried and true, or something new?

Once upon a time, when great recording studios were a “thing”, long before they became almost extinct—when no one thought such a thing was even possible—studio owners and sound conscious musicians competed with one another to find new and improved recording technology.

“Improved” came in many guises, some of which turned out to be worse. For instance, in the mid-1970s, the Aphex Aural Exciter grabbed the attention of both studio owners and musicians. It did what the name implied—adding “excitement” in the form of phase and frequency distortion when applied to vocals.

Properly used as a Band-Aid, it could “wake up” a multitrack tape that had “dulled out” from too many passes across the tape heads as fastidious perfectionists performed repeated takes. The Aural Exciter was so rare, precious, and sought after that, for a time, it was available only for rent by the hour.

Soon it became a craze. The Aphex Aural Exciter became a fashion employed to be heard; its spitty, bright sound ruining many an otherwise good production. Once recognized, its presence can’t be missed. No doubt many artists who got sucked into using it either by their producer or through their own desire to be au courant now regret it.

Later on, you could put Yamaha’s ubiquitous DX7 in the same category. It was the first programmable digital synthesizer and could produce an endless variety of unique sounds, but artists and arrangers, rather than learning how to create their own, used the presets. Almost half of ‘80s pop hits spotlit the same few “unique” and now obvious and tiresome sounds.

What does all of this have to do with Katy Lied, Steely Dan’s fourth album released in winter 1975? Read on!

The advent of tape recording was the most important studio development of the 20th century's second half, beginning with one mono track. Then two for stereo. Two recording tracks gave way to 3 for much of the 1950s, though first Les Paul in 1957 and later Atlantic Studios took delivery of 8 track recorders. By the mid ‘60s, 3 tracks gave way to 4, then 8, then 16, and by the end of the ‘60s, studios with money to spend and clients to impress went to 24 tracks on 2" tape.

More tracks meant narrower track width and more tape hiss. Ray Dolby introduced hiss diminishing Dolby Type A noise reduction in 1965—just in time for the multitrack tape boom. Six years later, in 1971, dbx introduced its noise reduction system.

In November 1974, Donald Fagen and Walter Becker entered what the duo would later characterize as the new “little” ABC Studios to record Katy Lied, produced by Gary Katz and engineered by Roger “The Immortal” Nichols. Pretzel Logic, the group’s previous album had been recorded at West Hollywood’s Village Recorders— still in business and the origin of dozens of superb sounding classics.

Summer of ’74, Becker and Fagen exited the road and found themselves in Los Angeles “…with no band, no manager, no plans to tour, no money, (and) some minor albeit possibly irreversible brain damage,” the reasons for the predicament not relevant here, though the decision to stop touring led guitarist Jeff “Skunk” Baxter to quit.

Nonetheless, what they did find in that “little” studio in addition to a brand new Bosendorfer piano was a double set of Magneplanar loudspeakers and a pair of Audio Research D-76 tube power amplifiers. Now that’s a system we can all relate to, though its utility as a studio monitor system is questionable. Perhaps then ABC Records President Jay Lasker was an audiophile and he was talked into using that as a studio monitor and perhaps he was also talked into some new, unproven “state of the art” studio gear.

Also in the studio and listed among the recording gear in the Katy Lied liner notes was a “specially constructed 24-channel tape recorder, a ‘State of the Art’ 36-input computerized mixdown console” and “some very expensive German microphones.”

Not mentioned in the liner notes and in the studio was “the world’s first and last dbx noise reduction unit with factory installed wings.” Someone convinced someone to install and use it instead of the more commonly used Dolby Type A noise reduction system. The selling point was an additional 10dB of noise reduction.

Yet, despite a strong set of ten smartly written, arranged and performed songs and a stellar cast of musicians Becker and Fagen hired to perform them (since there was no band)—including, among many others, Rick Derringer, Dean Parks, Hugh McCracken, Larry Carlton, Chuck Rainey, Wilton Felder, Hal Blaine, Victor Feldman, Phil Woods, and a very young Jeff Porcaro—sometimes it seems as if the real star here, at least among certain fetishizing sound conscious Steely Dan fans, is that dbx noise reduction unit!

It's a curious controversy set off by guitarist Denny Dias, who, other than Becker and Fagen, was the only remaining original band member appearing on Katy Lied. In an online story he titled “Katy and the Gremlin”, Dias recounts the problems encountered trying to mix the record, though it's unclear what his tech role actually was.

He writes: “Mixing was an absolute nightmare. Every song was mixed at least twice, and not because we were being fussy.” Becker and Fagen not “being fussy”? Right. Now there’s the first clue that something’s off here.

Next, he writes that the dbx system used to encode the multitrack tape channels couldn’t decode them and that the sound was “dull and lifeless”. Wait a minute. Both Dolby and dbx use pre-emphasis (in different ways) to boost frequencies, mostly at the top end of the frequency spectrum that are attenuated in the decode process. If the dbx couldn’t decode the tapes, the sound would have been “bright and harsh” not “dull and lifeless”. So if the tapes were sounding “dull and lifeless,” it would seem something else was at fault.

Then Dias writes, “We decided to remix the entire record using Dolby”. This doesn’t make sense. Dolby cannot be used to decode a dbx encoded multitrack tape. dbx encode was “baked into the cake”.

The Katy Lied Wikipedia post claims the dbx company fixed the problem and since the original pressing does not sound “dull and lifeless,” clearly it did fix the problem, but Becker and Fagen were still disappointed by the sound and supposedly didn’t want to listen to it. Fair enough. Musicians often don’t want to hear a finished record, preferring to move on to the next. And Katy Lied is not among the band's best sounding productions.

Sound obsessive Steely Dan fans continue to pick apart this record the way Kennedy assassination obsessives examine frame-by-frame the Zapruder film. Missing in the discussion are the contributions of the unnamed “state of the art” 36 channel computerized mixdown console so let’s stop right there: boards have a huge impact on sound quality! “State of the art” is a relative not an absolute term. Sometimes the "state of the art" is really poor! For instance, early "state of the art" solid state amplifiers and digital recorders.

We don’t know the computerized “state of the art” board’s provenance, but you can be sure it and the “small” studio acoustics had profound effects on the recorded sound.

So let’s forget the dbx conspiracy theories and whatever else may have contributed to how Katy Lied sounds and all agree that it is not the best sounding Steely Dan album, but once you get past the thumpy bass on “Black Friday” and a few other sonic cracks, it’s still a damn good sounding album (and I don’t care if Donald thinks otherwise!)—compacted and craftily mixed, with lots of keyboard and percussive magic going on within the mid frequencies—but clearly not as expansive or dramatic as Can’t Buy A Thrill or as crystalline clear as Aja .

This new UHQR absolutely destroys the 3 Kendun-mastered originals I have, as well as the bumpy and brittle ½ speed mastered Mobile Fidelity edition. That was the first Mo-Fi 1/2 speed mastered record I bought and I did so when it was first released hoping for a big sonic improvement. It was costly for me at the time and I remember being sorely disappointed though in some ways it was marginally better than the original, mostly because my system didn't have full bass extension nor was it fully extended on top.

While the sound quality varies from track to track and some are less than stellar, all sound better than the original pressing and the 1/2 speed remaster (I don't have the MCA 1/2 speed but few of those sound distinguished in my opinion). Here, if “Everyone’s Gone to the Movies” doesn’t sound stunning, don’t lay the blame on the recording or mix: the vibes, Fender Rhodes, bass, congas, marimba, sax and yes, the drum kit—including the nicely chiming cymbals—sound great! The drum fills that end the tune sound magnificent. And Fagen’s voice sounds as natural and “in the room” as you’ve ever heard it on record, especially this one.

Musically and compositionally Katy Lied is among the "band"'s best efforts (if you can call the rotating group of studio musicians accompanying Becker and Fagen a band), though it's emotionally kind of dry and anonymous. Still, there are no bad tunes and some great ones including the kind of creepy (but for many of us who reached adulthood around that time "universal") "Everyone's Gone to the Movies," the kind of sexy "Chain Lightning," the sort of optimistic "Any World (That I'm Welcome To)," and the "good times are gone" "Daddy Don't Live In That New York City No More." The album is "of a time." A time of cultural pessimism and decay that the album obliquely alludes to. That's all I'm going to say about the well-worn music everyone reading this surely knows

I don’t care how you’ve previously consumed this album, play this UHQR edition and you’re likely to have a “heard it for the first time” experience—at least on some tracks. I did, and I’ve been listening to this record for just short of 50 years. Not the best sounding Steely Dan album by far but the best sounding version of it that I've heard. Based on that, if we had a third knob for "reissue quality relative to previous versions," it would get a 10 or 11. But based on its intrinsic sound quality, 8 will do.