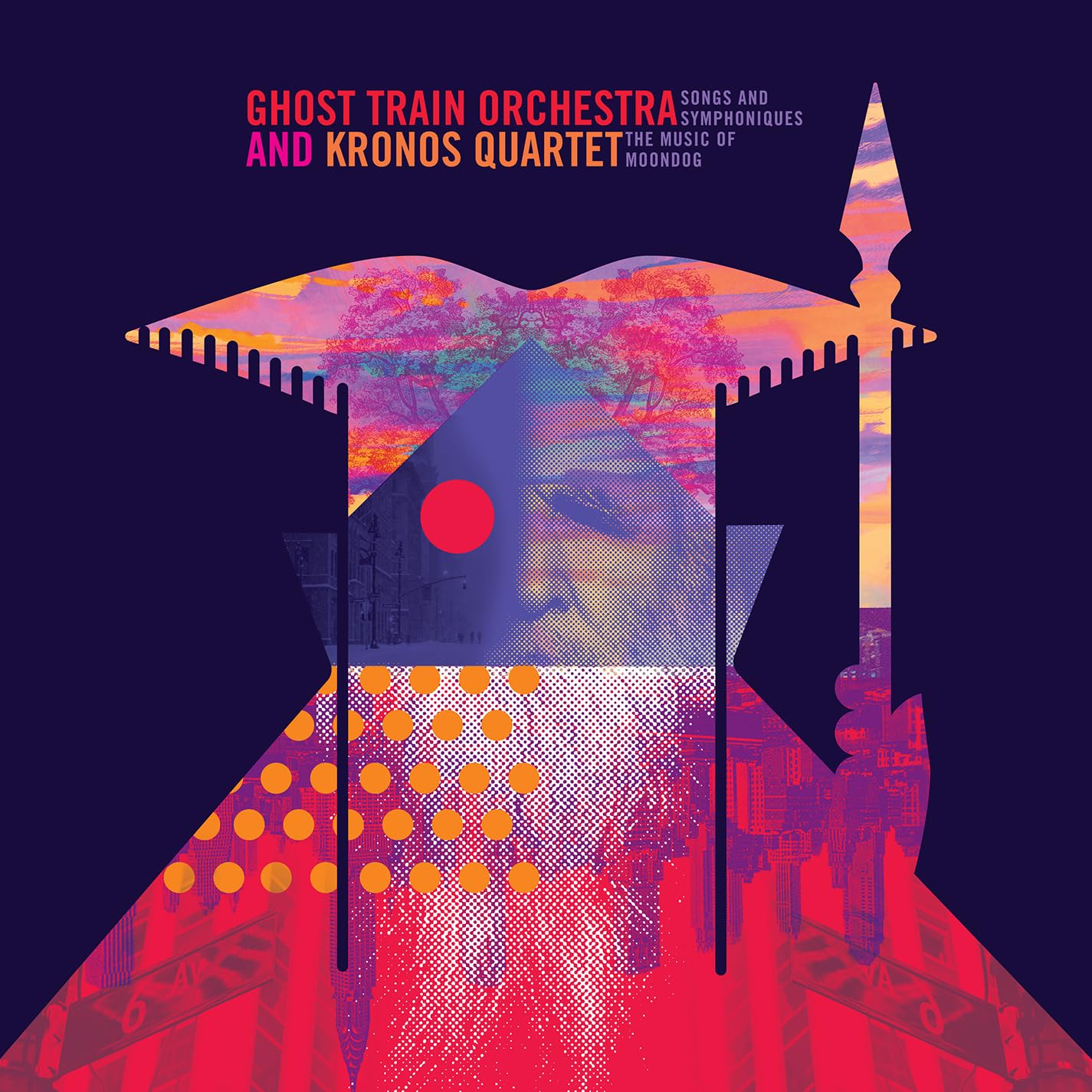

Moondog Comes Alive

Ghost Train Orchestra and Kronos Quartet revive the startling music of the Viking of 6th Avenue

Louis Hardin, who renamed himself Moondog, was one of the most unusual composers of the 20th century. Tall, bearded, and blind from a childhood accident involving fireworks, he spent much of the 1960s living on the streets of New York City, often standing ramrod straight at the corner of West 54th Street and 6th Avenue, dressed in square-patch clothing of his own making, his head cased in a Norse helmet (some dubbed him “the Viking of 6th Avenue”), playing his music, often on instruments he’d designed, selling his poems and recordings. Frequently profiled by columnists, an avid conversationalist with passersby, he may have been the most eccentric fixture in a city of eccentric fixtures.

But Moondog was also a serious composer—he wrote his music with a Braille stylus on stacks of cards in a technique that he invented—who impressed masters as varied as Charlie Parker, Duke Ellington, Julie Andrews, and Serge Koussevitsky, director of the New York Philharmonic, several of whose musicians played on the two albums that Moondog made for Columbia Records in 1959 and ’61, to much acclaim but little profit.

It wasn’t until the mid-1970s, when he moved to Germany for the rest of his life (he died in 1999, at the age of 83), that he became truly renowned, writing quartets and symphonies, conducting them in dozens of halls and studios across Europe. Even before then, in his New York years, he had a huge impact on Philip Glass and Steve Reich, who for a while played with Moondog—his music and theirs—every week. Glass, who put him up in his apartment for a year in the late ’60s, later wrote that he and Reich “took his work very seriously…understood and appreciated it much more than what we were exposed to at Juilliard.”

Now, Ghost Train Orchestra, a Brooklyn-based 13-piece ensemble, has teamed up with the Kronos Quartet for Songs and Symphoniques: The Music of Moondog, a double-album covering 17 of his compositions from his early to late period (the 1940s to ’90s), most of them arranged by GTO’s musical director, Brian Carpenter, some featuring singers Petra Haden, Rufus Wainwright, Marissa Nadler, Karen Mantler and Joan Wasser.

It is a splendid, engrossing, revelatory album. It’s also a lot of fun.

Moondog’s music is beyond category, drawing on, but never quite aligning with, classical, jazz, rock, bluegrass, medieval, Renaissance, and more. (As Glass suggests, you can also hear the high-fly glimmerings of what came to be called “minimalism,” especially on the tracks called “Theme” and “Bumbo.”) He wrote for a near-infinite range of ensembles, from solo percussion to full symphonic orchestra. (One piece he composed, which he actually conducted in Europe, was for 100 trombones.) Many of his pieces have seemingly simple melodies, but their harmonies are strangely rich and the rhythms are often difficult (5/4, 7/4 and more arcane time signatures); the combination of the primitive and the complex lent his music a pleasingly off-balance vibe.

Since his death, many musicians have covered his pieces, but none have been as virtuosic—as well-suited for capturing his spitfire spirit and ingenuous passion—as those assembled here. Ghost Train Orchestra specializes in underappreciated American music—its previous albums have covered obscure choir, chamber, and jazz pieces from the 1920s to ’40s—and, of course, Kronos routinely, and masterfully, performs music from all continents, genres, and eras. (After hearing a Kronos concert in Europe, Moondog composed a piece for the quartet, called “Synchrony No. 2”, which appears on its 1997 album Early Music, consisting of ancient music that sounds modern and modern music that sounds ancient.)

Songs and Symphoniques must have been a crazy hard album to record. It was made during the COVID lockdown, so much of it was slapped together from multiple overdubs. Ghost Train Orchestra recorded its tracks at Bunker Studio in Brooklyn. The files were sent to Kronos, who laid down their parts, sometimes together at East Side Studio in Manhattan, but more often separately in their homes in San Francisco—first to cellist Sunny Yang, who overdubbed her part, then sent the resulting file to violist Hank Dutt, who did the same and forwarded it to 2nd violinist John Sherba, who followed suit and passed it on to 1st violinist David Harrington, who recorded his part and sent it back to Ghost Train’s Brian Carpenter. (And, by the way, yes, the quartet sounds better—the strings more vibrant, the ensemble more charged up—on the songs recorded at East Side.)

It's amazing that the music comes off as lively—and as good-sounding—as it does. Don’t expect an audiophile wonder, but it’s a wonder of its own sort nonetheless.

Here are two "home brew" Moondog YouTube documentaries: