"The Greatest Recording Ever Made": The Decca/Solti "Ring" Cycle Revisited - PART 2: Creating a "Theatre of the Mind"

A deep dive into the story of how Decca came to make the first studio recording of Wagner's epic cycle "Der Ring des Nibelungen"

Before I get into the detail of the making of the Decca/Solti Ring, some history of what led up to Decca’s embarking on this massive project.

The Origins of Decca’s Ring

The Decca Ring did not appear out of nowhere. Nor was there ever a definite plan to do a studio recording. The sheer scale of the enterprise was too daunting creatively, logistically, and, of course, financially. So first thoughts ran to taking advantage of the fact that Bayreuth was already mounting a full-scale production every Summer. Why not simply record that, in situ?

The First Long-Playing Record

The First Long-Playing Record

With the arrival of the long-playing record in 1948, courtesy of Columbia Records, the possibility of recording complete operas in high-fidelity sound with a minimum number of disc sides had become a reality. With the re-opening of the Bayreuth Festival in 1951 there was renewed focus on using the new medium to capture complete performances of Wagner in that unique acoustical space.

There began a cut-throat competition between Decca and EMI to become, as it were, the “official” record label of Bayreuth. Walter Legge, the legendary head of EMI’s classical division, used every means at his disposal to thwart Decca’s attempts to record a complete Ring cycle, but his company’s early recordings of other Wagner operas at Bayreuth were not met with enthusiasm by the Festival directors Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner, who were also the composer’s grandsons.

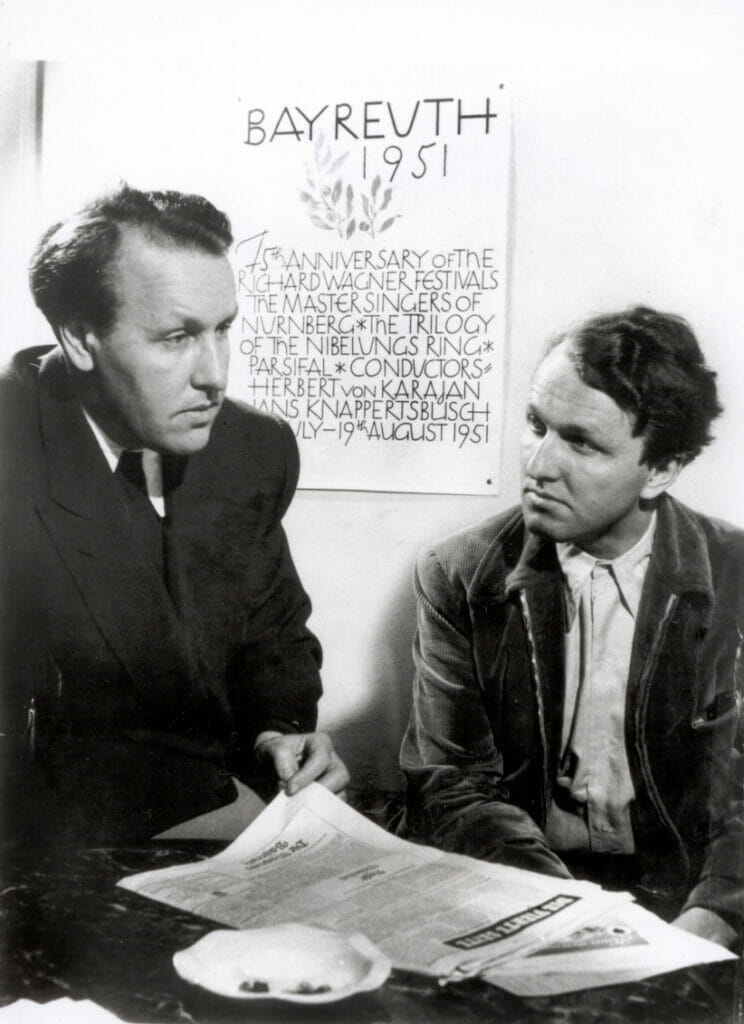

Wieland (l.) and Wolfgang Wagner, the Composer's Grandsons

Wieland (l.) and Wolfgang Wagner, the Composer's Grandsons

With the arrival of LPs, Decca began to make a real mark with its opera recordings, captured in vivid sound owing to its roster of first-class engineers (like Kenneth Wilkinson) who were not afraid to rewrite the book of sound engineering. The ongoing success of Wieland Wagner’s revolutionary Ring cycle (which had debuted in 1951), with its minimalist sets and abstract lighting, was making waves in terms of how opera productions looked. It was also highlighting several generations of outstanding Wagner singers who could also meet the acting demands of Wieland’s concepts: names like Kirsten Flagstad, Martha Mödl, Astrid Varnay, Hans Hotter, Wolfgang Windgassen, and later stars like Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Birgit Nilsson. For most opera lovers, these singers still represent the final Golden Age of Wagner singing.

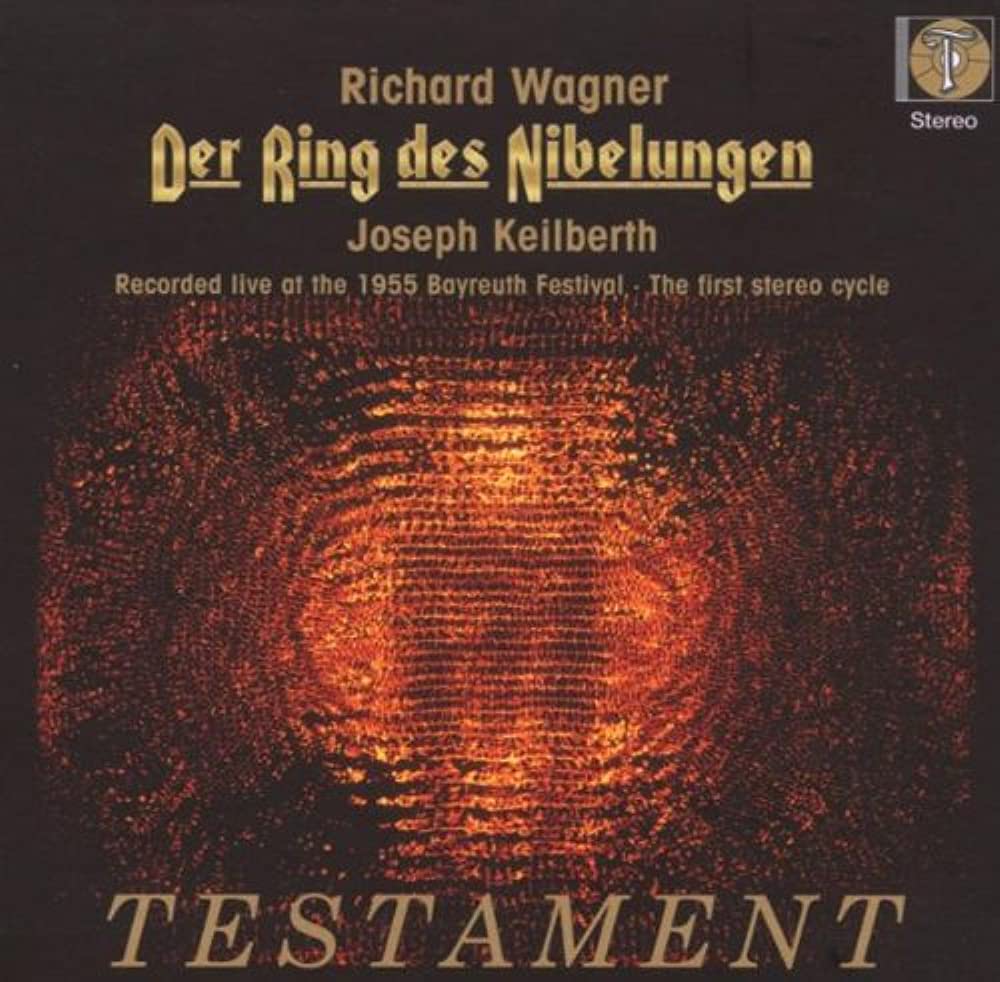

So in 1955 Decca secured the rights to record the complete Bayreuth Ring cycles that were being conducted by Joseph Keilberth.

Joseph Keilberth

Joseph Keilberth

The team consisted of both Decca and Teldec engineers (Teldec was Decca’s German affiliate), and was headed by Peter Andry at the beginning of his illustrious career. The British engineers included Kenneth Wilkinson (supervising the mono recording), Roy Wallace, and a young Gordon Parry, who would go on to supervise the Solti Ring.

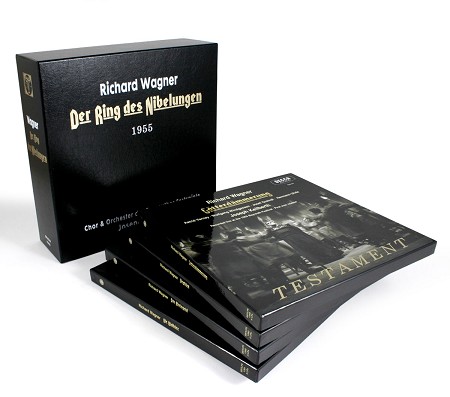

Everyone involved thought this was going to be the first complete Ring cycle not only on record, but also in stereo. However this historic recording was not released until 2006 (on Testament CD and vinyl) for a myriad of legal reasons. It is remarkable both musically and technically, and should be on everyone’s short-list of great Ring recordings - despite the intrusion of stage noise. You will hear many of the singers from Solti’s subsequent studio set, but in younger and sometimes finer voice.

The Keilberth "Ring" on CD

The Keilberth "Ring" on CD

The Keilberth "Ring" on LP

The Keilberth "Ring" on LP

Even though this isn’t the main recording under consideration here, it’s worth taking a moment to remark on just how technically accomplished the Decca engineers proved to be under the most demanding of circumstances. No doubt their experience of recording a complete cycle “live” stood them in good stead for the future Solti enterprise. The Testament booklet includes these recollections by Roy Wallace as to how the recording team met the considerable challenge of working in the Bayreuth theatre:

“For a start, you had the orchestra underground beneath a canopy. Here we just managed to place three Neumann M49 microphones in about the only place they could possibly go. You didn’t have a chance to move anything, and just hoped for the best! The other three M49s had to be hung from the lighting bridge, about 20ft above the stage. This was brilliant; it worked beautifully. These mikes were all fed into the Decca-constructed six-channel mixer model ST2 (designed by Wallace himself). Two AEG TR9 tape machines were operated by my German colleagues Hans Redlip and Hans-Joachim Klemp as recording had to be continuous….. I had Gordon Parry in the stereo room with me, reading the score and telling me what was going on. Sadly the AEG tape machines proved unreliable and the Ampex machine which I had brought from London as a backup had to be substituted on one occasion.”

Now Kenneth Wilkinson (considered to be one of the greatest of all classical recording engineers) had been recording at Bayreuth since 1951, working with Decca’s producer John Culshaw, and loved the experience of recording “live”, a view not shared by Culshaw, who subsequently left Decca for a brief sojourn at Capitol Records. Returning to Decca in 1955, the same year the live Ring was recorded, Culshaw was more interested in capturing a complete cycle on records under optimized studio conditions.

John Culshaw with Birgit Nilsson

John Culshaw with Birgit Nilsson

John Culshaw is an enormously important figure in the history of classical recording. Quite apart from the monumental achievement of the Decca/Solti Ring, Culshaw set the gold standard for excellence in the presentation of classical music in what were then new media. His ongoing collaboration with Benjamin Britten on both records of his own music, and as a conductor/pianist, are jewels in the Decca catalogue, as are his series of opera recordings for the label.

Culshaw also defied commercial expectations: the Ring and Britten’s War Requiem, neither exactly easy listening, sold in the many millions and have never been out of the catalogue. The 3lp box set of Das Rheingold outsold contemporary records by Elvis Presley and Pat Boone!

In 1967, Culshaw left Decca to become head of music programs at BBC Television, pioneering a series of “live-in-studio”, fully staged, opera broadcasts that were ground-breaking, just part of a series of innovations he brought about to “sell” classical music to as wide an audience as possible. Like Leonard Bernstein, Culshaw was the great proselytizer on behalf of classical music.

For Culshaw, the best way to record an opera was under optimum studio conditions, using every bell and whistle to bring the drama and music into the listener’s home as vividly as possible - to create what came to be known as a "theatre of the mind". He had long nursed an ambition to record a complete Ring cycle, and had used the opportunity to record parts of Die Walküre with the great Kirsten Flagstad as a dry run. For the 1958 recording of part of Act 2 and all of Act 3 he was able to secure the services of the up-and-coming young Hungarian conductor Georg Solti. (Culshaw had attended a live performance of Die Walküre thrillingly conducted by Solti in Munich in 1951). These recording sessions confirmed in his mind that Solti was the man for the job of tackling the full cycle.

The Decca set of Records that paved the way for the Recording of the Complete "Ring" cycle

The Decca set of Records that paved the way for the Recording of the Complete "Ring" cycle

Solti considered the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, with its distinctive sonority, to be the pre-eminent orchestra for Wagner in the world. Decca already had the orchestra under contract, and had long experience of recording it in the acoustically superb Sofiensaal. After the success of the two earlier Walküre sets, the go-ahead was given for embarking on the first studio recording, in stereo, of Das Rheingold.

Recording the Decca/Solti Ring

As Culshaw explains in his introductory note included both with the original and newly remastered vinyl sets of Das Rheingold:

“Our basic concern was the sound which, whatever its texture at any given moment, was required always to be beautiful, balanced, and yet endowed with an indefinable something which I will call, for want of a better word, impact. It has nothing to do with loudness, as such, nor with presence, at least if the latter is taken to mean the dry, disagreeable sound which is created by placing microphones too close to the source of the sound. And we did not see why this basic sound should not be to some extent variable, according to the scene and the scoring and the prevailing dramatic mood. Rheingold is very much a sequence of moods, which are conveyed just as much through orchestral colorings as through vocal expression and phrasing.”

This emphasis on capturing the ebb and flow of the sound of Wagner’s work is the key to understanding why the Decca Ring is so successful. It’s not just a matter of the painstakingly accurate sound effects Culshaw introduced to reflect specific stage directions Wagner wrote into the scores (like the 18 anvils clunking away in tempo during Wotan and Loge’s descent into the dwarves’ realm of Nibelheim); nor is it a matter purely of the fidelity of the recording itself (although that is certainly integral). It’s a question of the creative team fully understanding Wagner’s world-building in text and music, getting under the skin of the score, and conveying those intentions fully, purely, in sound alone.

Culshaw continues:

“None of us who faced the task of recording Rheingold had, on the face of it, any cause at all to worry about visual considerations; we were lucky, in that the medium we were working in enabled us to dodge the trickiest problems of all [like simultaneously swimming and singing Rhinemaidens - MW]. Yet precisely because none of us had ever seen a really convincing stage production of the work, we found that in order to bring aural imagination to work it was first necessary to visualize the piece scene by scene. We did not have to worry about whether what we visualized would work or not on the stage; but we had to know exactly what it would look like before we were able to decide how it should sound. What happens when Alberich becomes invisible and chases Mime with a whip? Where exactly does Donner stand in relation to the others when he wields the hammer? What is the picture at the end when the Rhinemaidens are heard in the distance? It may be different for other people, but I have always found it impossible in the studio to judge any such perspectives in sound unless I have a clear image in my mind of how the scene, ideally speaking, should look….. In studying the work, we therefore started with the music, which led us to the visualizations I have mentioned, which in turn led us back to the music and its detail, wherein lay the justification or denial of what we proposed to do.”

So how did Culshaw and his team go about achieving all this? Well, the starting-point would always be capturing the music itself in the most vivid manner current technology could provide. Here Decca was in an excellent position going into the project - they were not working from a blank slate. Firstly, everyone had gone through the experience of recording live performances at Bayreuth, with all the attendant challenges and compromises involved. Secondly, even as early as 1958, Decca, along with the RCA Living Stereo and Mercury Living Presence teams in the US, had proven its ability to capture complex classical music in stereo with maximum fidelity and impact by using remarkably simple microphone set-ups.

As Dominic Fyfe, the Producer of this new Ring reissue, states in his program notes:

“Decca’s celebrated microphone tree - left, right and centre mics above the conductor paired with left and right outriggers - was barely four years old and constantly evolving in the hands of Decca engineers Roy Wallace and Kenneth Wilkinson.”

Solti conducting the VPO, and above his head you can catch a glimpse of the mics on the Decca "tree"

Solti conducting the VPO, and above his head you can catch a glimpse of the mics on the Decca "tree"

The Decca "Tree" as pictured in the 2022 Rheingold Booklet

The Decca "Tree" as pictured in the 2022 Rheingold Booklet

Kenneth Wilkinson, in many ways the Jedi master of Decca’s crack team of sound engineers, was not involved in the Decca Ring. The young Gordon Parry, who had been pestering Culshaw to record a complete Ring for years, was in charge of the technical team, and it is no small measure of his achievement that Culshaw’s excellent book about the process of recording the first stereo Ring cycle, titled Ring Resounding, should be dedicated to him first, and then the conductor Georg Solti.

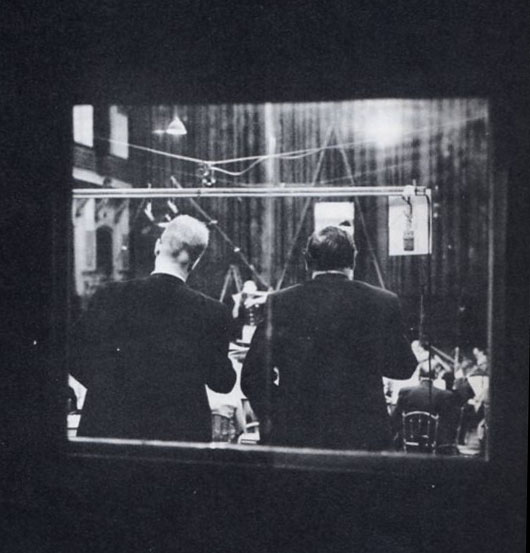

Gordon Parry

In the Sofiensaal Control Room: (l. to r.) Jimmy Brown, John Culshaw, Gordon Parry

In the Sofiensaal Control Room: (l. to r.) Jimmy Brown, John Culshaw, Gordon Parry

Fyfe notes:

“Surprisingly, he [Parry] eschewed the increasingly fashionable omni-directional microphones (even today Decca still utilizes Neumann M50 omnis on its tree), instead favouring a tree of three cardioid Neumann KM65s with left and right outriggers of Neumann M49s in wide cardioid configuration. The vocal microphones - three suspended on a boom covering the Sofiensaal’s stage - were also M49s with their cardioid pattern finely adjusted to have control of the voices without clouding the orchestral balance. Cardioid microphones are so-called because their directional pattern looks like the shape of a heart: favouring the front and sides over the rear. For Parry the result was a visceral orchestral sound allied to a clarity of the voices as they moved about Decca’s sonic stage: a grid of numbered squares around which the singers moved to create the aural illusion of Wagner’s theatrical directions”.

This grid enabled Culshaw to precisely place and move the singers within the stereo soundstage “live”, a far more elegant approach than the later technique of multi-tracking each voice and manipulating perspectives in post-production. When I was recording live radio drama in front of an audience in the early days of digital (when we could only record in 2-channel stereo) I used Culshaw’s technique, and it not only worked like a charm for the audio recording, it gave the actors room to imagine themselves into the physical space of the scene, and gave the audience visual cues to the scene, rather than just watching the actors simply standing at their respective microphones.

Another important innovation Culshaw and his team introduced was to record in much longer segments than was customary at the time. Most operas were recorded in takes of 5 minutes or less; on the Ring uninterrupted takes of between 15 and 20 minutes were the standard. Of course this was more demanding for performers and technicians alike, but it meant the musicians could really settle into the momentum of a scene, and capture something of the energy of a live performance.

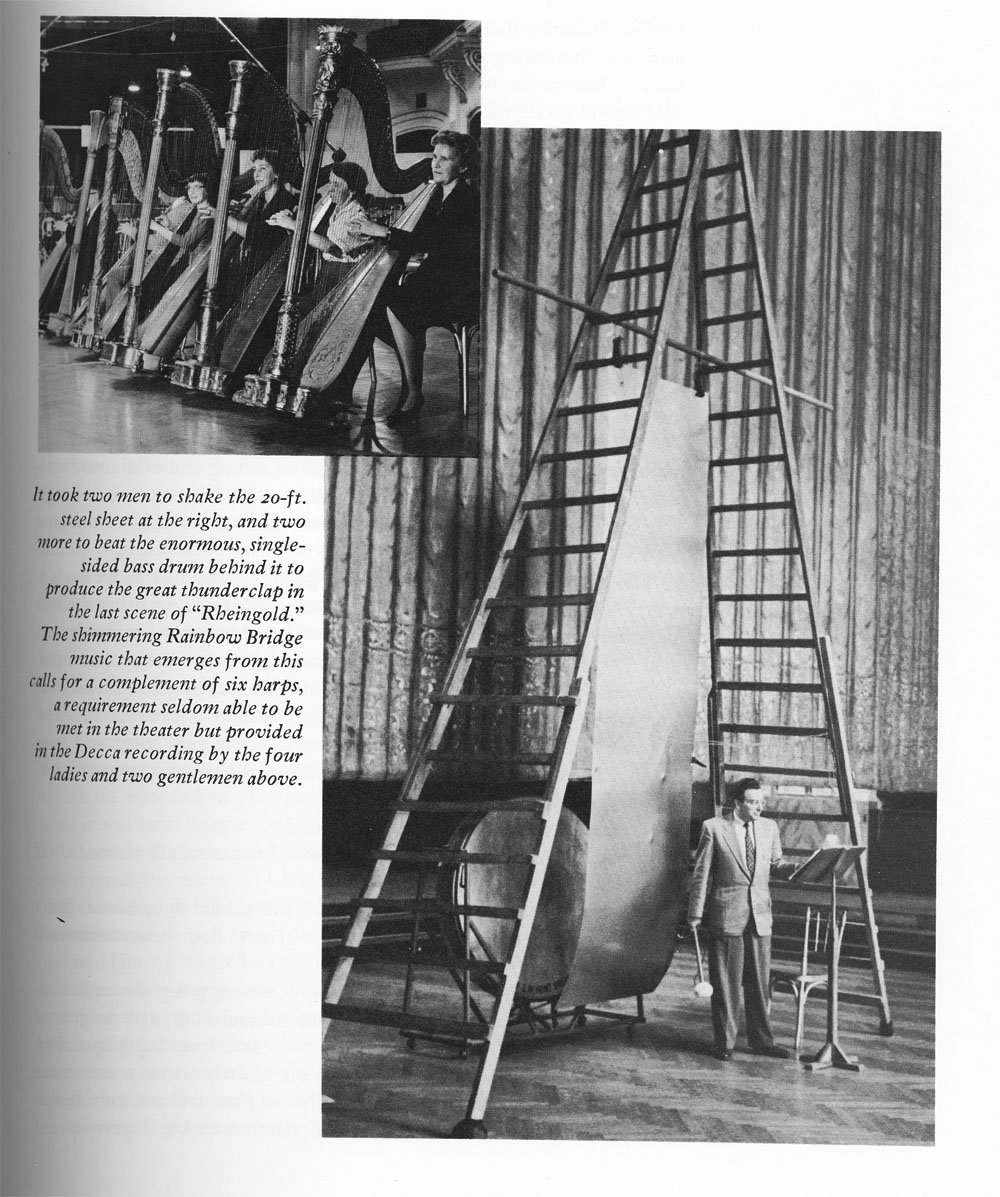

A key element in creating an audio recording faithful to Wagner's intentions was to follow, where possible, his stage directions with regards to added sound effects, or specific instrumental requirements. For example, for the storm conjured up by Donner at the end of Das Rheingold, Culshaw and his team had to come up with a mighty hammer blow and thunderclap. The results are thrilling.

Creating Donner's Hammer Blow

Creating Donner's Hammer Blow

Another effective aural creation comes earlier in the opera when Wotan and Loge descend to the dwarves' realm of Nibelheim, brilliantly described in Wagner's music. At a certain point we begin to hear the hammering anvils of Alberich's slaves, and for this Culshaw came up with 18 tuned anvils.

Later in that same Nibelheim scene, the recording team had to come up with a way to make Alberich sound "invisible" as he dons the magic Tarnhelm and persecutes Mime. The solution was to put Alberich into an isolation booth and treat the voice before it went to tape.

Alberich's Isolation Booth

Alberich's Isolation Booth

For the key scene in Götterdämmerung where the villainous Hagen summons up his vassals, the team had to have authentic steer horns constructed and then played from an offstage room to create a realistic sense of the men approaching from a distance, responding to Hagen's calls.

The Steer Horns in "Götterdämmerung"

The Steer Horns in "Götterdämmerung"

These are just a few examples of the lengths to which the sound engineers went to capture some of the more esoteric sound elements in the Ring.

The Decca Ring had several other not-so-secret weapons at its disposal. First, there was the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra which, as far as Solti and Culshaw were concerned, was the orchestra with the quintessential Wagner sound. This had a great deal to do with the distinctive wind and brass instruments that have been used in Vienna over many generations. Vienna existed as something of an island musically, and these instruments were built differently to their equivalents in other orchestras, thus featuring their own unique sound. One prime example of this are the French horns which have a richer, rounder sound than their American or British counterparts.

The VPO Horn Section and 4 Wagner Tubas

The VPO Horn Section and 4 Wagner Tubas

The VPO is also famous for its lush but sweet string tone, and for Solti this blend of timbres represented the perfect Wagnerian palette. Today, as orchestras around the world pretty much all sound the same, the VPO still retains its own signature sound and playing style. Back in the late 50s and early 60s when the Decca Ring was recorded, these qualities were even more pronounced. When you listen to the brass blowing full tilt in, for example, Siegfried’s Funeral March, it is utterly thrilling, and unlike any other recording.

Extract from BBC Documentary showing Solti recording Siegfried's Funeral March

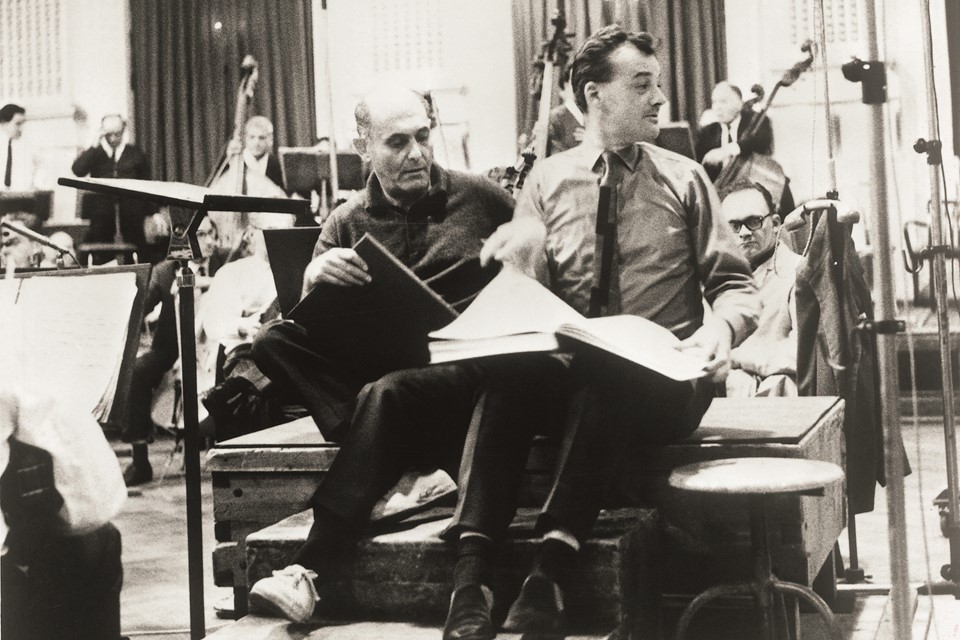

Which brings us to the choice of conductor, Hungarian emigré Georg Solti. In his book Ring Resounding, Culshaw recalls the first time they worked together:

“Solti had come to London to record Haydn’s Symphony No. 103, the Drum Roll, with the London Philharmonic in Kingsway Hall, and I was given the sessions because Victor Olof was recording on the continent. There remains only a vague recollection of Solti’s vitality and enthusiasm and cooperation - a realization on my part that making a record could be more than the routine business of putting so many notes of music into a groove. Apart from anything else, the sound that Solti was able to produce from the orchestra was exciting, and I longed to work with him again on something which, in that particular sense, offered more scope than Haydn”.

Solti with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Solti with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

One of the hallmarks of the Decca Ring is the momentum and thrilling orchestral sound conjured up by Solti. Some have said the performance is too hard-driven; it certainly occupies a different universe to Furtwängler’s more languid (but no less gripping) approach. But I prefer to characterize Solti’s performance as well-paced, keeping the drama moving along, with enormous attention paid to bringing out every detail of the orchestral texture. Solti is also completely on-point with regard to supporting his singers, giving them exactly what they need to shine in terms of pacing and balancing them against the orchestra. (Remember that these recordings were made long before multi-tracking was a possibility: the balancing of the different elements is largely done live by the conductor).

Interestingly, Solti did not conduct a complete Ring cycle in the opera house until 1964 when he was music director at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden. His helming of the 1983 production at Bayreuth in collaboration with renowned British director Peter Hall, has gone down in history as one of the great misadventures of the work in that house, and Solti did not return for the production’s revival the following year.

And so to the cast. Solti gathered together the foremost Wagnerian singers of the day. Some, like George London, Kirsten Flagstad, Hans Hotter, Gustav Neidlinger and Wolfgang Windgassen, were the stars of the inter-war years, now in, or approaching, the sunset of their careers. They bring an unmatched authority to the proceedings. Others, like Regine Crespin, James King and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, were the new guard, being given an unparalleled opportunity to make their mark in this landmark recording. Chief amongst these younger singers was the great Swedish soprano Birgit Nilsson, who is frankly god-like in her ability to nail one high note after another in her signature role of Brünnhilde. At the end of Götterdämmerung, during the massive Immolation Scene in which she alone commands the stage for some twenty-plus minutes, you totally believe she is the one person with the authority to bring the whole sorry mess crashing to earth as she declares her undying love for the dead Siegfried - and gives the finger to the gods. Nilsson went on to make many more recordings for Decca, most memorably essaying the leading roles in Richard Strauss’s two shock-and-awe operas, Elektra and Salome, again produced by Culshaw and conducted by Solti with the VPO. (Seek out original Decca/London pressings, or the Speaker’s Corner reissue of Elektra - they will give your system one hell of a workout!)

Birgit Nilsson with Georg Solti and John Culshaw

Birgit Nilsson with Georg Solti and John Culshaw

Look further down the cast list and there are many surprises. Joan Sutherland - a future star in the operatic firmament - sings the small but crucial role of the Wood Dove in Siegfried, Christa Ludwig shines early in her recording career as Fricka in Die Walküre. In that same opera the ranks of the Valkyries contain three future Brünnhildes: Brigitte Fassbaender, Helga Dernesch, and Berit Lindholm (whom I saw essay the part brilliantly in the Götz Friedrich/Colin Davis Ring at Covent Garden in the 1970s). In Götterdämmerung who should show up as Rhinemaidens but Lucia Popp and Gwyneth Jones, the former a future beloved singer of a wide repertoire, the latter another Brünnhilde in the making.

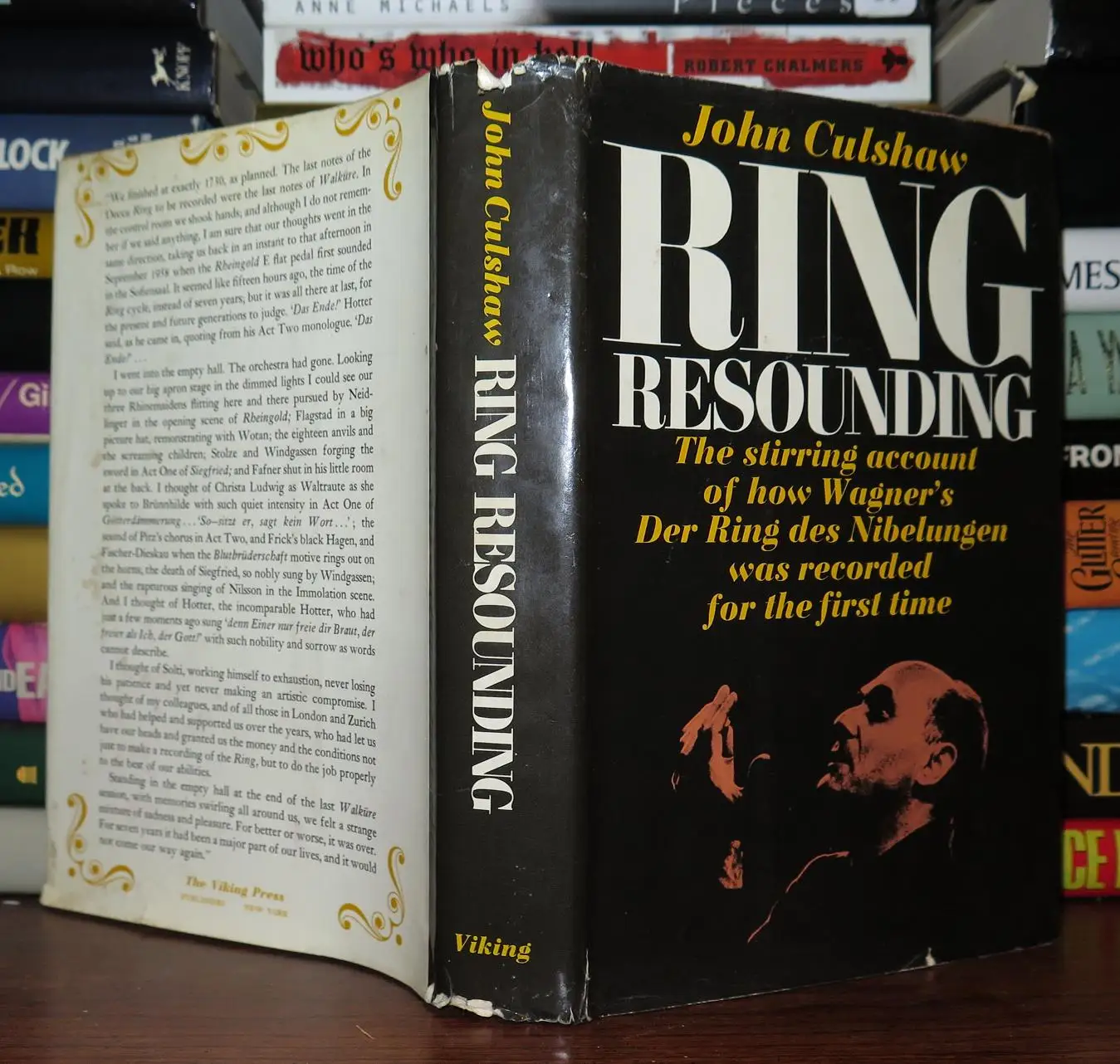

For anyone interested in diving more deeply into the making of this iconic set, there are two excellent resources, both of which I have already mentioned in passing. The first is John Culshaw’s account of the whole process in his book Ring Resounding.

It is an easy read, and a riveting account of the many trials and tribulations, as well as the great victories, that created 19 records of musical history. One of the most touching aspects of the book is Culshaw’s account of his friendship with the legendary soprano Kirsten Flagstad - a leading Brünnhilde and Isolde in her day - who sang Fricka in Das Rheingold.

Kirsten Flagstad as Brünnhilde

Kirsten Flagstad as Brünnhilde

His dogged attempts to get her back into the studio, forever thwarted by her ill health, are most touching. Elsewhere his account of how Birgit Nilsson thought the recording of Götterdämmerung was a disaster because she had listened to a test pressing of the Immolation Scene on a faulty playback system will raise a knowing chuckle among audiophiles. Culshaw and Parry had to go to elaborate lengths to get the soprano to listen to the record on a decent system. As Culshaw comments on the episode:

“I shall never know what was the matter with [Nilsson’s] machine in New York, but the moral of this tale is clear: if a major recording produced by one of the big companies sounds seriously deficient in one way or another, technically speaking, the chances are more than likely that the fault is with the playback equipment and not with the record. In one form or another this sort of problem is the daily bane of classical recording executives, and nobody knows how to solve it except by making the public more conscious of what constitutes good sound.”

Culshaw goes on to recount how a leading music critic denigrated one of his records for a lack of bass. Sending an engineer over to assess what was going on, he found out that: “…. not only was there a serious deficiency on the bass side, but also that he was reviewing all his records with the bass control fully retarded, and the top control fully advanced. Yet he had blamed the record, and never given a thought to his machine.”

The book charts every aspect of getting a successful recording made, from the conception, casting and recording through to the editing (a huge part of the Ring project), getting the records physically made, presented to critics and marketed to the public. Mid-way through the project the team decided to completely redesign their mixing console, no small task in itself. It's a fascinating behind-the-scenes look at an extraordinary undertaking.

The second resource I'll mention is the excellent documentary The Golden Ring, made by Humphrey Burton for the BBC during the recording sessions for Götterdämmerung in 1964. Culshaw insisted this be a true fly-on-the-wall approach, with nothing specially staged for the cameras, and the result is fascinating. Anyone who thinks recording an opera is boring stuff will be rapidly disabused of the notion. Watching Solti command his forces with almost manic energy is its own special thrill. The film also includes the wonderful moment when, as Birgit Nilsson is about to embark on recording the tetralogy’s final Immolation scene, in which Brunnhilde summons her horse and rides onto her dead lover Siegfried’s funeral pyre, bringing about the end of the world as we have known it, a real horse was marched onto the stage and presented to her.

Birgit Nilsson meets her horse, Grane. (Note the grid marked out on the stage to give the singers their positions for moving around what Decca came to call its "Sonic Stage")

Birgit Nilsson meets her horse, Grane. (Note the grid marked out on the stage to give the singers their positions for moving around what Decca came to call its "Sonic Stage")

The film is available on DVD, but also pops up regularly on YouTube.

If you don’t have time to watch the whole thing, sample the sequence where the evil Hagen (sung to powerhouse perfection by Gottlob Frick) summons his vassals, with a chorus of on- and off-stage steerhorns (the instruments were specially reconstructed for the sessions). This starts at 15:30 and continues until 23:10.

Continued in Part 3, where I will assess the sound quality of the different versions on vinyl, CD and SACD of the Decca "Ring".

You can read Part 1, covering the history of opera leading up to Wagner, the composition of the "Ring", and production challenges and history, here.