"The Greatest Recording Ever Made": The Decca/Solti "Ring" Cycle Revisited - PART 1: The Operas and their History

A Deep Dive into Wagner's Epic Cycle of Four Operas, Its Place in Musical History, and the Making of this Groundbreaking Recording

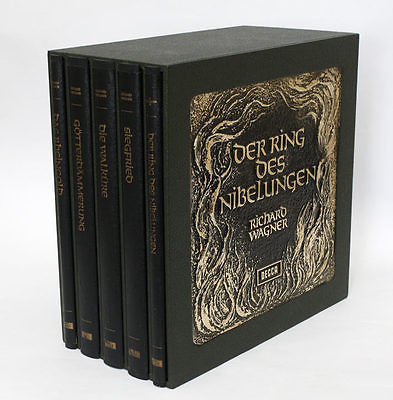

The phrase “classic of the gramophone” gets bandied around a lot, but this is one set of records that fully deserves that lofty title. What we have here is 19-LPs spread across 4 box sets, recorded between 1958 and 1965 in Vienna with that city’s legendary orchestra - one of the greatest in the world - together with a who’s-who cast of top Wagnerian singers from that era, all under the baton of the then emerging powerhouse conductor Georg Solti. Each of these box sets was a best seller when it was first issued, outselling major popular artists like Elvis Presley. Since then these albums have never been out of print in whatever was the current media of the time: vinyl, cassette, CD, SACD. The recordings themselves have been remastered several times, but this new 2022 remastering goes back to the original stereo master tapes for the first time in decades.

Why this work? Why this set of recordings? What is so special here?

To understand that you have to understand the singular nature of Wagner’s ambition and achievement in this cycle of operas that is simply known as “The Ring” (short for “Der Ring des Nibelungen” or “The Ring of the Nibelung”). Not only did these works re-write the rule book for opera, they established a new template for epic art. Without the example of Wagner, would we have had the work of authors like J.R.R. Tolkien with his Lord of the Ring saga, C.S. Lewis with his Narnia novels and sci-fi trilogy, and J.K. Rowling with her Harry Potter saga, let alone their film equivalents and the Star Wars universe? The Ring’s exploration of fundamental themes of power, innocence, love and transcendence are also common to all these works: but it was Wagner who cast the original mold for much of our modern epic entertainment.

Richard Wagner

Richard Wagner

Wagner started out writing operas like Rienzi (1842) that were very much in the style of what was fashionable in the early and mid-19th century: grand Romantic opera, often based on historical events, in the vein of Weber and Meyerbeer. But in his theoretical writings, Wagner developed the notion of the Gesamtkunstwerk (loosely translated as ‘total work of art’ or ‘all-embracing art-form’) in which opera would bring together and synthesize other art forms into a glorious dramatic whole. Gone would be the excesses of 19th century French Grand Opera (with its nonsensical plots and two-dimensional characters serving pure theatrical spectacle), and what he perceived as the vocal histrionics of the so-called bel canto school in which everything was subservient to the star singers engaged in endless vocal acrobats. (Some wag would later coin the term can belto to describe this school of operatic singing).

Wagner was inspired by the aesthetic purity of Greek tragedy, and the operatic reforms of his German predecessors, Gluck and Weber. (The latter’s opera Der Freischutz, with its supernatural plot and somewhat expressionistic musical idiom, is a harbinger of both German Romanticism and Wagner’s preoccupations).

_of_'der_freischutz'_1822_weimar_-_ngo4p1115.jpeg) Set Design for Wolf's Glen scene in "Der Freischütz", Weimar 1822

Set Design for Wolf's Glen scene in "Der Freischütz", Weimar 1822

In the Gesamtkunstwerk the libretto would hold primacy, with the music, scenery, lighting, costumes, and acting serving a coherent dramatic structure. By turning to mythology as his source material, Wagner hoped to tap into the fundamental themes that drive human nature and society. (Some one hundred years later, George Lucas took the same path with Star Wars, inspired by the analysis of mythological archetypes shared across cultures contained within Joseph Campbell’s 1949 book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces).

The Ring is a work which, for better or for worse, is inextricably bound up in the political and creative turmoil of the years since it was first performed as a complete cycle in 1876 in the opera house built by Wagner for the specific purpose of presenting this new art-form under optimum conditions: Bayreuth.

Bayreuth Festival Theater

Bayreuth Festival Theater

Politically, Wagner was a lightning rod for controversy both during and well beyond his lifetime, as Hitler and the Third Reich latched onto his ideas and music to bolster their totalitarian and genocidal agenda. Many musicians and music lovers still refuse to play or listen to Wagner.

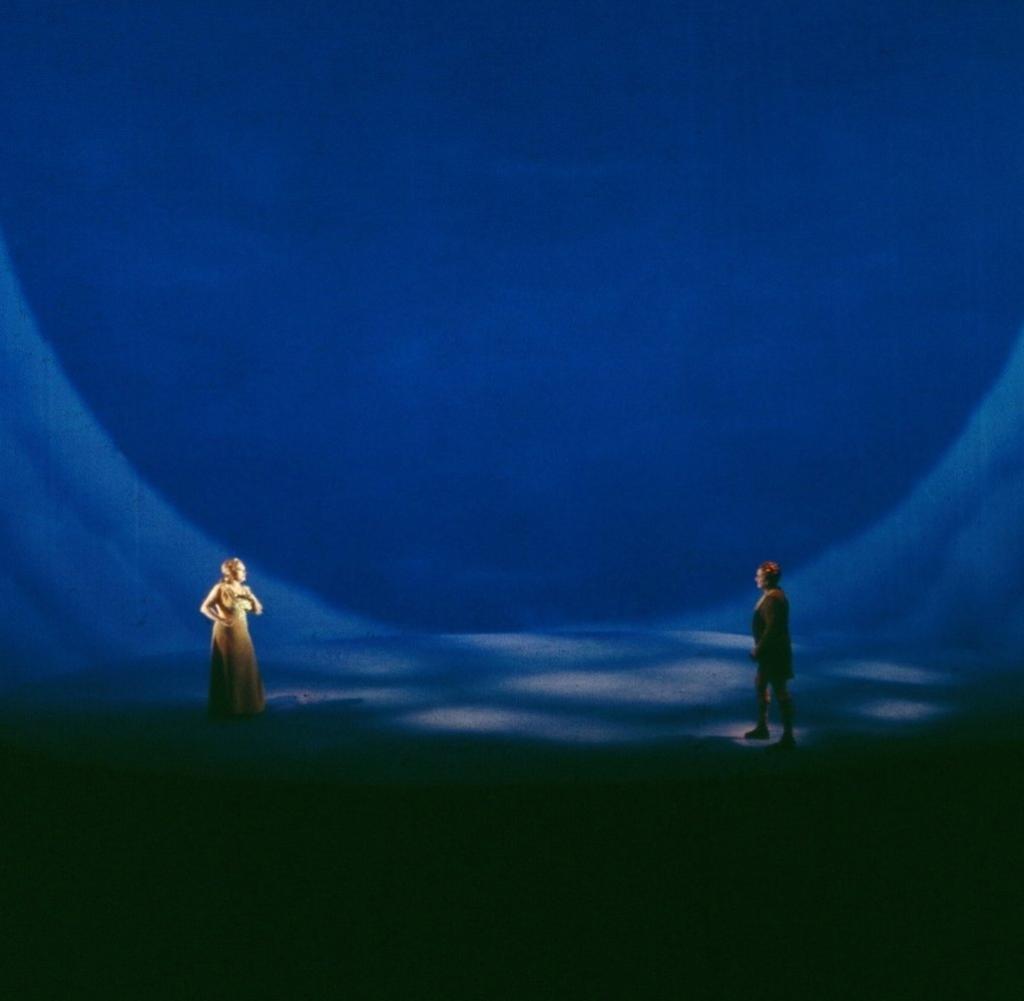

The Ring demanded and inspired a complete re-evaluation of the operatic form and how it is presented on stage and on film. No composer who has written an opera since has been able to ignore it: either one copies its compositional procedures or one actively rejects them. Likewise, when it came to the theatrical mise-en-scene, even though the early Bayreuth productions adopted a naturalistic approach, Wieland Wagner (the composer’s grandson) developed a more abstract canvas when Bayreuth reopened after the War. His productions proved to be enormously influential not only on Wagner productions in particular, but on all areas of the theater arts.

A Scene from Wieland Wagner's Production of "Das Rheingold", with Valhalla represented purely by Light Projections

A Scene from Wieland Wagner's Production of "Das Rheingold", with Valhalla represented purely by Light Projections

Opera houses around the world aspire to staging a complete Ring cycle, a Herculean task in terms of casting, staging - and cost. Record companies during the heyday of classical recording - from the 1950s to the early 2000s - competed to complete their own cycles. But Decca got there first, and the Decca Ring - despite some flaws - remains the standard against which all others end up being judged.

The 1970 Edition of the Decca/Solti "Ring"

The 1970 Edition of the Decca/Solti "Ring"

To fully understand the significance and ground-breaking nature of the Decca Ring, you first have to understand how central opera was in the development of Western music, and how radically Wagner changed the form. To do that, there follows a brief account of how opera came into being and developed up until Wagner. That will be followed by an account of the Ring’s creation and production history leading up to the Decca recording.

Later on (in Part 2) I will outline the remarkable story of the Decca sessions and how all involved pushed the art and science of recording forward to accommodate the enormous demands of the project. After that, I will discuss in detail the sound on all the different iterations of this recording, including the new 2022 vinyl and CD/SACD editions.

What is Opera and Why Does it Matter?

The World's First Opera House - San Cassiano in Venice (1637)

The World's First Opera House - San Cassiano in Venice (1637)

If you asked people today what is the dominant form of pop culture, most would say film. It is the medium that combines more of the arts than any other, and it is massively popular worldwide.

But in the middle of the 19th century, when Wagner embarked on the Ring, the answer to that question would have been - opera.

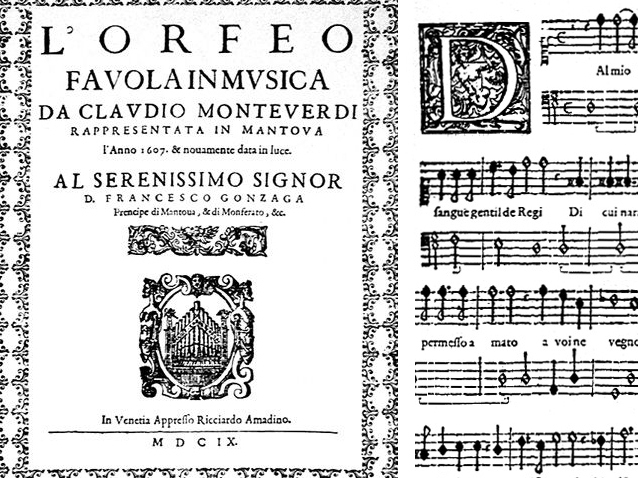

Opera grew out of a variety of musical entertainments that combined music with a story, and was eventually codified into more-or-less the form we know today by a group of Italian composers in the late 1500s who were inspired by the knowledge that Ancient Greek dramas had, to some extent, been sung. While it is not considered the first opera, Monteverdi’s retelling of the classic Greek myth L’Orfeo in 1607 is considered the first masterpiece of the genre. In subsequent works like Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria (The Return of Ulysses to His Native Land, 1639) and L’Incoronazione di Poppea, 1643) he further developed the operatic form to its earliest peak.

Original Printed Score for Monteverdi's "L'Orfeo"

Original Printed Score for Monteverdi's "L'Orfeo"

To fully understand the significance of the opera form you have to appreciate that in the period following the collapse of the Roman Empire, music - like literature - was mainly the province of the Church, for hundreds of years. Most music that was written down was composed and performed as part of religious devotion. This began with monophonic - or Gregorian - chant, where monks would sing the same line in unison. This evolved into early polyphony during the 12th century in the Cathedral of Notre Dame when the composers Leonin and Perotin starting to compose music in 2, 3 or 4 parts. Texts would be drawn from the scriptures, and the individual syllables of words would be extended beyond recognition. This was not song as we think of it, where the text is clearly audible and the music amplifies its meaning. Here the text is merely a vehicle for elaborate, drawn-out musical lines that reflect and meditate upon the Divinity.

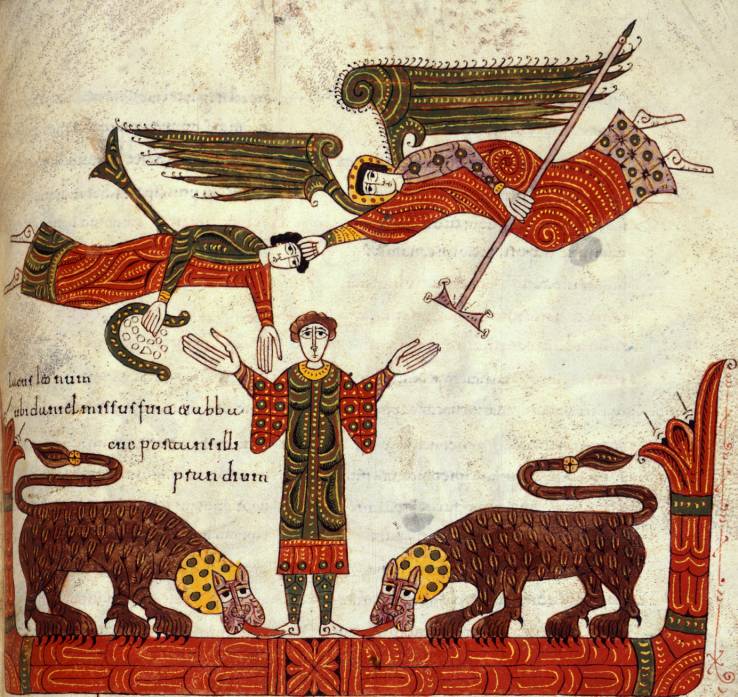

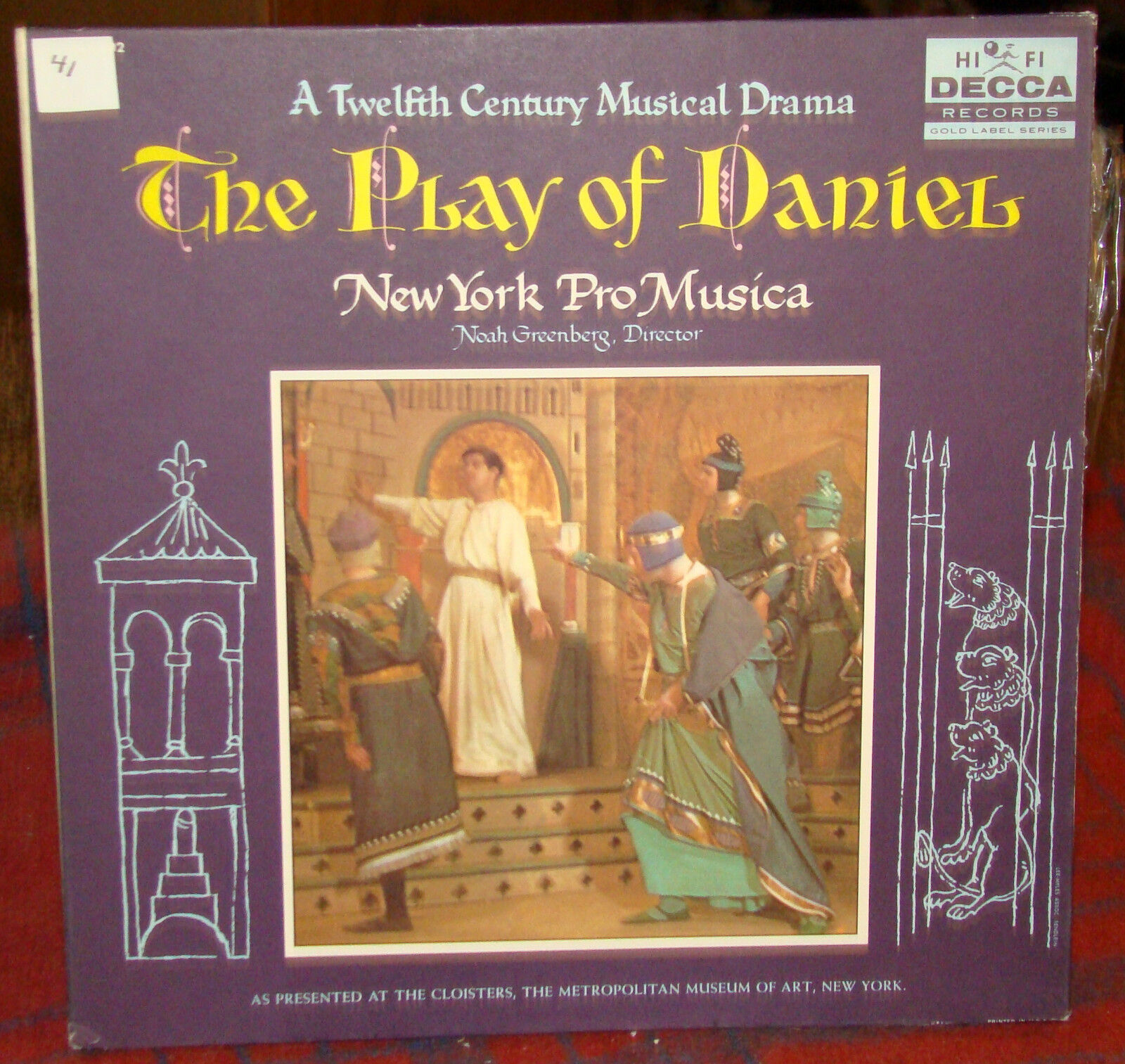

An important work to note here is The Play of Daniel, a liturgical drama based on the Book of Daniel, that first appeared in spoken form in the early 12th century. Monophonic music was added to it in the 13th century.

Daniel in the Lion's Den by Petrus (Spain, 1109)

Daniel in the Lion's Den by Petrus (Spain, 1109)

Albeit a sacred work, this anticipates the opera form by several centuries. The instinct to inject music into a dramatic, theatrical work is clearly present very early on in the development of Western culture. A seminal series of performances in modern times took place in New York in the 1950s under the leadership of Noah Greenberg, director of New York Pro Musica, with the distinguished poet W.H. Auden providing commentary. Decca subsequently recorded and released a performance recorded live at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. (There have been several excellent recordings since by Boston Camerata and The Dufay Collective).

Now, concurrently with the development of sacred music, you see the rise of secular music in folk song and melodic instrumental music. Here the words are absolutely supposed to be heard and understood. Unlike religious music, secular music also had a strong rhythmic drive, easily grasped by the listener, and was often designed to be danced to.

As we move into the Renaissance we see the lines between sacred and secular music become more blurred, and the great composers of the period - like Monteverdi - are often writing in both genres. But in both it is the human voice which holds the primary position - more often than not expressing either heavenly or earthly love.

What opera does is it provides an arena for the composer and his dramatist to essentially fuse sacred and secular music. They can combine the immediacy and textural clarity of secular song with the more extended compositional methods of sacred music, and give the whole thing extra punch and depth by being part of an overall dramatic story.

Over the next few hundred years opera developed in different ways, but it’s fair to say that the emphasis remained largely on the singers. In the Baroque era, composers like Handel worked within a more-or-less standard format. The story would be moved along in what was called recitative, in which the singers would speak-sing conversationally and quickly on repeated pitches to the accompaniment of the harpsichord, sometimes embellished with a ‘cello on the bass line or other plucked instruments like the lute or theorbo. When there was a moment in the story that required a character to reflect more deeply about the dramatic situation (and their emotions), there would then be a fully composed aria in which the full orchestra would join in. The words for the aria would be of a more poetic hue. These arias mostly took the da capo form, where the first section would be sung as written in the score, followed by a second section often at a different speed, and then the first section would be repeated but with the vocalist adding extensive ornamentation, usually improvised on the spot. Occasionally there would be duets or ensembles, and sometimes a chorus would chime in.

First Edition Score for Handel's "Rodelinda"

First Edition Score for Handel's "Rodelinda"

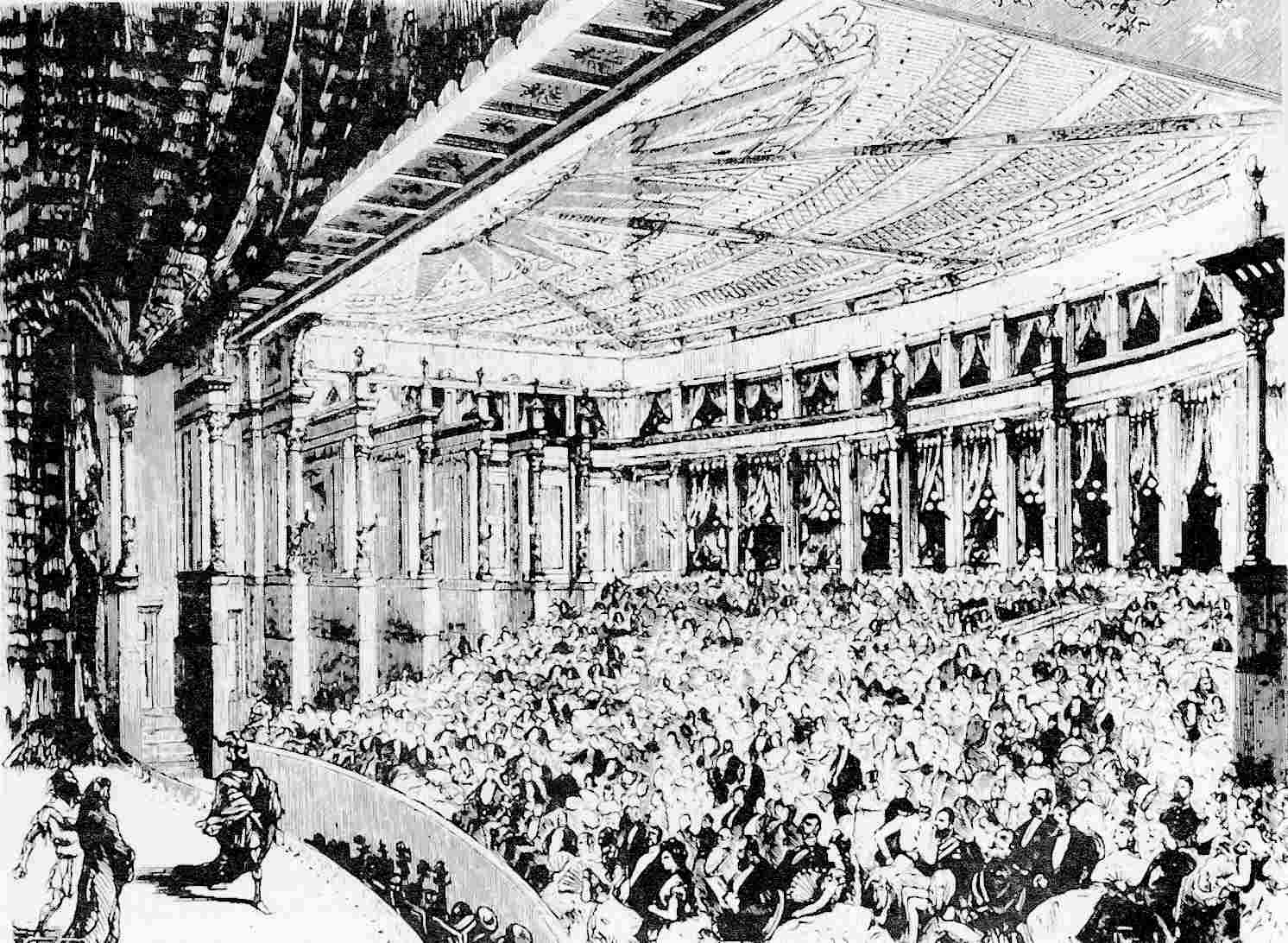

Within this standard form a variety of stories were told, sometimes based on history or myth, sometimes comedic, sometimes a blend (just as in Shakespeare where even the most tragic tales often have comedic scenes and characters). The story, and the libretto, were subservient to the needs of the composer. It was all about music heightening the emotion of the dramatic moment. Through his success in opera in London, Handel enjoyed enormous popularity and wealth of an order rarely achieved by other composers of his time. Over in France, the extravagances of the Court of the so-called Sun King, Louis IV, gave rise to the grand entertainments of Lully and Rameau.

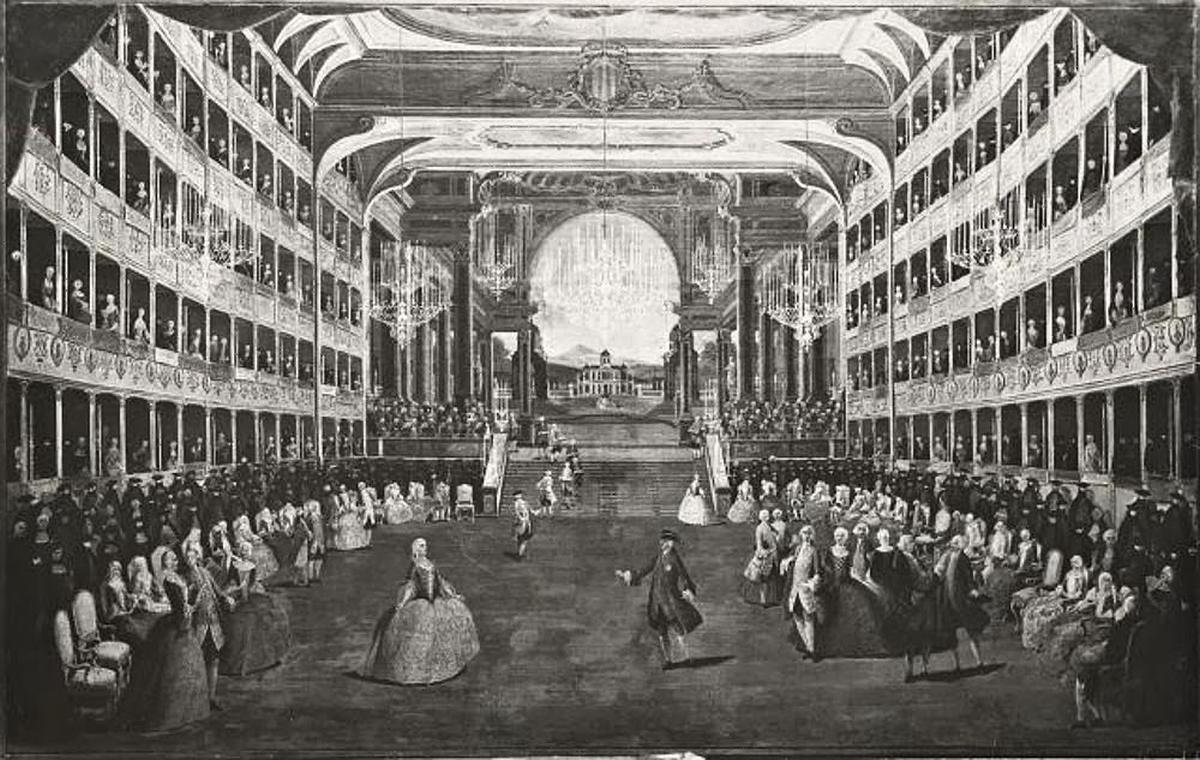

Opera Performance at Versailles

Opera Performance at Versailles

As the classical era dawned, opera began to further stratify into different genres, dividing domestic drama/comedies away from historical period pieces and more earthly, burlesque-style entertainments. Mozart, for example, composed in all three operatic genres in vogue during his lifetime, and pushed each into new levels of sophistication. For the opera buffa you have his extraordinary trio of Le Nozze di Figaro (1785-86), Don Giovanni (1787) and Cosi fan Tutte 1789-1790). All three sported sophisticated libretti by Lorenzo da Ponte which integrated serious dramatic elements within the high jinks audiences expected of the buffa form. And while Mozart continued to work in the established format of aria and recitative, he also began to through-compose long sections of the work, anticipating Wagner by nearly a century. For the opera seria (serious opera) - often based on mythological or historical narratives - Mozart composed works like Idomeneo, Re di Creta (1780-81) and La Clemenza di Tito (The Clemency of Titus, 1791). Finally, for the German singspiel, where the libretto was in German and instead of recitative the plot was moved along by spoken text, Mozart completely elevated the genre with works like Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio, 1781-82) and Die Zauberflote (The Magic Flute, 1791).

David Hockney's Celebrated Set Design for "The Magic Flute"

David Hockney's Celebrated Set Design for "The Magic Flute"

Operas were so popular, and the art-form was considered so highly, that most composers wrote them - or at least attempted to. (A major exception was J.S.Bach, whose predominant vehicle for musical drama was the Passion, in which he used many of the formal devices found in Baroque opera to serve the religious drama of Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection).

Haydn, remembered today mainly as the first master of the nascent “sonata form” found in the symphony and string quartet, actually wrote fifteen operas, rarely performed after his death until the late 20th century (when the gramophone played a major role in bringing these back into the light with Antal Dorati’s pioneering recordings for Philips in the 1970s and 80s). Beethoven famously labored long and hard over his one contribution, Fidelio (1805), which went through two earlier incarnations (titled Leonore) before he settled upon its final form.

Striking Set Design by Barkow Leibinger for "Fidelio" at Theater an der Wien (2020). You can clearly see the influence of Wieland Wagner's minimalist, abstract approach.

Striking Set Design by Barkow Leibinger for "Fidelio" at Theater an der Wien (2020). You can clearly see the influence of Wieland Wagner's minimalist, abstract approach.

In the 19th century, with the dawning of Romanticism, opera - not surprisingly - kicked into high gear. High emotion, high-stakes drama, all the bells and whistles of a symphony orchestra in the pit, plus spectacular scenery and costumes - what else could so perfectly convey the Romantic sensibility? Giacchino Rossini became the avatar of Italian opera during the first half of the century, now best-known for his frothy comedies like Il Barbieri di Seviglia (The Barber of Seville, 1816), but also capable of writing grander affairs in the French manner like Guillaume Tell (William Tell, 1829). Retiring from formal composition in his late 30s, Rossini passed the mantle to Bellini, Donizetti and Verdi.

What you can clearly see as you survey the history of opera is how the majority of composers felt it was the one challenge they had to take on. Certainly there were exceptions. Brahms, for example, showed no interest in opera: the windmills he was forever tilting at were the symphony and concerto. But for most composers, writing a successful opera represented the ne plus ultra of musical greatness, because it demanded a composer call upon all his abilities of harmonic and melodic invention, orchestration, vocal and solo instrumental writing, and, of course, a sense of drama. Putting on a successful opera demanded the absolute best from everyone involved.

How Wagner Reinvented Opera

This rich and extensive legacy of opera was the world into which Richard Wagner plunged headlong. Unlike most major composers you care to mention, Wagner more or less restricted himself to this one musical form. Also unique was the fact that he wrote his own libretti. His initial outings in the genre like Rienzi (1842) were cast in the mold of French grand opera, but in turning to the mythical subject-matter of Der Fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman, 1843), Tannhäuser 1845), and Lohengrin (1850), Wagner found a way to move into material that better reflected both his intellectual and musical obsessions.

Wagner as a Young Man (photo by Franz Hanfstaeng)

Wagner as a Young Man (photo by Franz Hanfstaeng)

For a man like Wagner, whose interests and passions extended far beyond the world of music, and frequently got him into very hot political water, opera provided the ideal vehicle with which to further his idealogical agenda. Composing an opera was world-building, and rising to the challenge of doing this in a way unique to him was fully the match for Wagner’s profligate ego.

It’s reasonable to say that by the time Wagner embarked on his quest to create the ultimate gesamtkunstwerk, articulated in his essays The Artwork of the Future (1849) and Music and Drama (1851), opera had more often than not fallen prey to its own excesses. I have sat through a production of Meyerbeer’s L’Africaine (1865) at Covent Garden, and I do not care to repeat the experience - pace the fact that Meyerbeer was the star of the operatic world at the time Wagner was starting out. Meyerbeer, along with Rossini, was the most popular opera composer of the first half of the 19th century, his works requiring vast resources to be performed.

A popular postcard of the time, showing Meyerbeer's Apotheosis, surrounded by his most famous characters (Bulla Frères, c.1865)

A popular postcard of the time, showing Meyerbeer's Apotheosis, surrounded by his most famous characters (Bulla Frères, c.1865)

Wagner, in a manner hardly untypical for him, was initially a fan of his fellow countryman, then turned against him as his own ideas of the way forward for opera diverged from those of his idol. Nor did it help that Meyerbeer was Jewish, rich, and had once turned down Wagner’s request for a loan.

(This is neither the time nor place to dwell on the more repellent aspects of Wagner’s character, but they are there in plenitude, and he remains the poster boy for asking the question of whether great art trumps the vile nature of its creator, or vice versa).

Part and parcel of his ruthless megalomania was the single-minded ambition that enabled Wagner to so thoroughly “take on” the musical establishment and reinvent the operatic form. Living in exile in Switzerland after incurring the wrath of several European nations, Wagner began to put his theories into practice with the writing of what would become the libretto for a vast enterprise: Der Ring des Nibelungen, comprising three lengthy music-dramas preceded by a prelude (itself the length of a normal opera of the time). Once the libretto was completed he began the composition, completing the prelude, Das Rheingold (1854), plus Die Walküre (1856) and the first half of Siegfried. He broke off work on the Ring to devote himself to a new project, Tristan und Isolde, inspired by his obsessive love affair with Mathilde Wesendonck, the wife of one of his most generous patrons. (This was not the last time Wagner would express his gratitude to a benefactor by bedding his wife. The conductor Hans von Bulow - who led the premieres of several Wagner operas - had to look the other way while his spouse Cosima, the daughter of Franz Liszt, moved in with Dick W., and even bore him three children while still married to the conductor).

Cosima and Richard Wagner

Cosima and Richard Wagner

When Wagner resumed work on Siegfried some twelve years later, his music had been greatly enriched by the revolutionary score he had provided for Tristan, in which the composer had pushed the tonal system - the bedrock of western music for nearly a thousand years - to the breaking point.

(Sidebar: This aspect of Wagner’s evolution as a composer is essential to understanding how Romantic music led into the collapse of tonality and the fragmentation of early 20th century music. To mirror the doomed love affair of Tristan’s protagonists, Wagner wrote a score of intense chromaticism. In conventional tonality, the home chord or key of a piece of music - the tonic - goes through a series of migrations which take the music into different keys before usually returning to the tonic. A composer exploits the tensions of different keys and harmonies in relation to the tonic, including transitional discords, to keep the music interesting, moving forward. As music became more complex harmonically in the 19th century, mirroring the subjective viewpoint of Romanticism, these digressions into ever remoter keys away from the tonic became more and more extended, creating a sense of suspension in the listener. Discords were no longer used in passing, they eventually became the main feature. In Tristan und Isolde, Wagner plays with this idea of tension and non-release to mirror the thwarted sexual desire of the two lovers. You can hear this in the famous opening Prelude, where the music never seems to resolve. In the big Act 2 love duet the music builds and builds towards its expected release, only to be side-swiped at the climax when the lovers are interrupted. This is the most notorious coitus interruptus in all art. In fact the opera only resolves to its home key, or tonic, after four hours of non-gratification, as Isolde literally finds love in death, expiring on the body of her dead lover, as she sings the Liebestod.)

As Wagner neared the completion of his epic with Götterdämmerung (The Twilight of the Gods), he was able to draw upon the financial resources of his long-time, utterly besotted benefactor, King Ludwig II of Bavaria, to build his own opera house to his own specifications in the small Bavarian town of Bayreuth, where the Ring was first presented in its entirety in 1876 and annually or biennially ever since.

The First Performance of "Das Rheingold" at Bayreuth in 1876

The First Performance of "Das Rheingold" at Bayreuth in 1876

One of the main features that sets the Bayreuth Festival Theatre apart from all other opera houses is the fact that the orchestra pit extends under the stage. This means the orchestral sound blends together before it goes out into the auditorium, mingling with the singers above who do not have to strain to make themselves heard. Also, no light escapes the orchestra pit, so all the audience sees is the stage action, creating an almost cinematic illusion in the theatre, an effect unique to Bayreuth.

Apart from the interruption provided by the de-Nazification process after World War II, the Festival reopened in 1951 and has continued every summer since then, presenting selections from the entire Wagner canon as well as the Ring.

What is the Ring?

Drawing on a range of Norse and German mythology, the Ring tells the story of a Ring of power and how it wreaks havoc amongst men, dwarves, giants and Gods eager to harness it for their own gain. (Sound familiar?) It all begins with a lovesick and feckless dwarf called Alberich who just wants to get some action from the flirtatious Rhinemaidens who guard the precious gold at the bottom of the Rhine. They lead him on and then humiliate him.

Alberich with the Rhinemaidens (Arthur Rackham, 1910-1911)

Alberich with the Rhinemaidens (Arthur Rackham, 1910-1911)

In retaliation Alberich renounces love and steals the gold, forging from it the Nibelung’s ring of the tetralogy’s title.

In the early parts of the drama the dominant figure is Wotan, the King of the Gods, whose unsuccessful attempts to acquire the ring to maintain the established order (and his position at the top of that order) cause all kinds of complications involving his own illegitimate and incestuous children, and one very unhappy wife. The ring passes into the hands of the young, innocent hero Siegfried - the fruit of an incestuous one-night stand between two of Wotan’s bastards. (Siegfried was subsequently adopted by the Nazis as the embodiment of Aryan purity). Wotan sees the writing on the wall: the age of Gods is passed, the age of Men is nigh. Siegfried falls victim to Palace intrigue created by Alberich and his own bastard son, Hagen. The opera ends when Siegfried’s lover, the woman-warrior Brünnhilde (another progeny of Wotan, and co-incidentally Siegfried’s aunt) dons the ring, rides onto his funeral pyre, and brings the world - gods included - crashing down, to be covered by the waters of the Rhine, whereto the ring and its gold return.

Brünnhilde Rides onto Siegfried's Funeral Pyre

Brünnhilde Rides onto Siegfried's Funeral Pyre

The Rhinemaidens are happy once more, and the final music is of redemption by love.

I know it all sounds a bit ridiculous, but trust me: when you are sitting in a darkened theatre and that opening music emerges out of the depths at the beginning of Das Rheingold, you are totally in thrall.

And this is where we get to probably the most important and revolutionary aspect of Wagner’s creation. In order to fully capture the many characters, ideas and levels of meaning in this complex music drama, Wagner created a new mode of composition: what he referred to as leitmotif technique. What he did was to use melodies of various lengths, or rhythmic phrases, or chords, and to associate them with a specific character, idea, even object in the unfolding drama. Then he combined these in a constantly shifting framework of music in the orchestra (sometimes spilling over into the vocal lines) that underpins the entire work. Sometimes the leitmotifs refer to something that is happening onstage, sometimes they call back to something that has already happened, sometimes they call forward to something that has yet to happen. It is a brilliant compositional coup. It means that you are never lost, the music is always telling you what is going on, or suggesting connections and intimations you hadn’t thought of. The voices almost become superfluous, since the drama is unfolding so comprehensively in the musical accompaniment. Quite apart from the brilliance of the concept, it is a display of virtuosic compositional technique, executed to perfection. It is actually quite mind-boggling to consider how it’s done.

Here, members of the brass section of the Metropolitan Opera House Orchestra offer an introduction to the leitmotif technique used in the Ring.

This technique has found its way into many areas of classical music. Probably the most evident example is film music. The young Erich Wolfgang Korngold, fleeing the rise of Nazism in Europe, brought the technique to his ground-breaking scores for films like The Sea Hawk (1940) and The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938). His contemporary Max Steiner also used the technique in his scores, like Gone with the Wind (1939). John Williams revived the technique in a major way for his Star Wars scores and the many others that followed.

Allied to Wagner’s innovative leitmotif technique was his adventurous use of the orchestra itself. The scoring is so varied, with one texture giving way to another, all crafted with such skill, that the voices, many of them facing long performances, do not have to compete to be heard. (In regular opera houses with a regular pit, the singers have more of an uphill battle than they do at Bayreuth). Wagner is constantly varying the orchestration, saving the big guns for moments when the singers are silent. Listen closely to the famous Ride of the Valkyries: he allows each individual voice to cut through and have its moment, while always maintaining the momentum of the “ride” in the background. It’s only when the valkyries are all singing together that the orchestra comes in at full blast - it’s a thrilling effect.

Realizing the Ring Onstage

Before I get into the details of how John Culshaw went about realizing the Ring on record, I want to talk about the unique problems facing anyone trying to mount this work on the stage, and how this keyed into the Decca team’s approach.

The action of the Ring takes place in a range of naturalistic settings, like mountains, caves, woods, Royal palaces etc., with gods and giants, men and dwarves as the protagonists. The very beginning of Das Rheingold is supposed to take place by and in the waters of the Rhine, with the three Rhinemaidens swimming while they sing! The original stage productions of the first two operas in Munich, and the first complete cycle at Bayreuth in 1876, respected the mise-en-scene laid out in the libretto, so everything was represented on stage as realistically as possible: real forests, real mountains, real dragon etc.

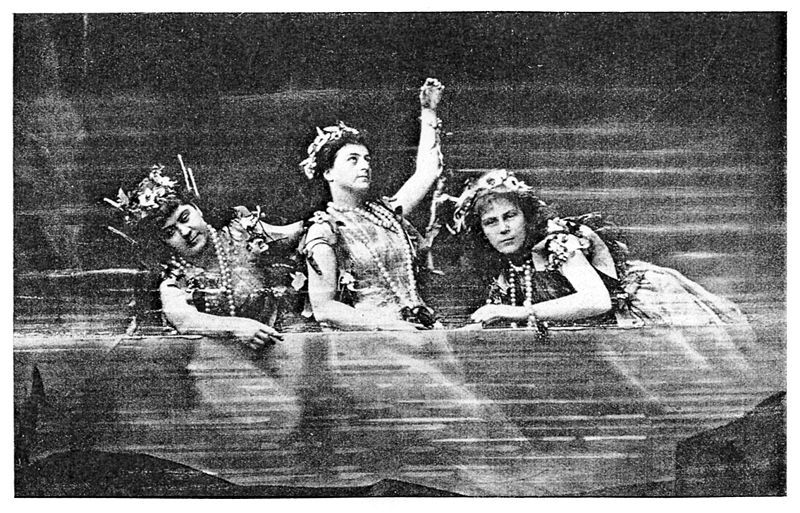

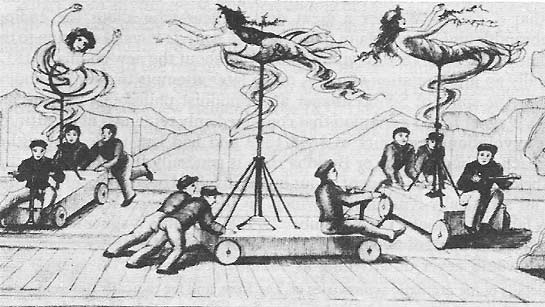

Rhinemaidens in the First Bayreuth Production of "Das Rheingold" in 1876

Rhinemaidens in the First Bayreuth Production of "Das Rheingold" in 1876

Making the Rhinemaidens "swim"

Making the Rhinemaidens "swim"

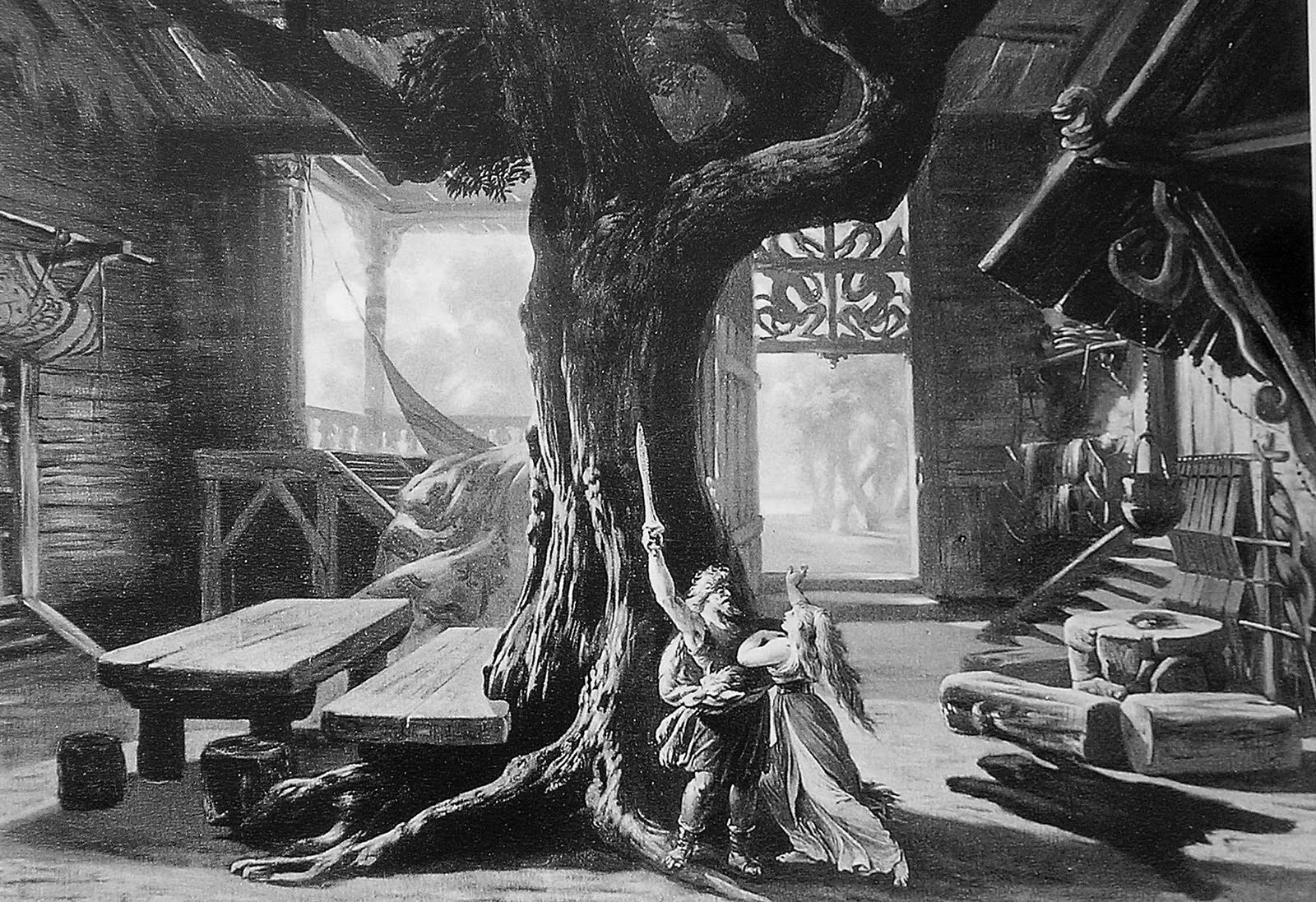

"Die Walküre" Act 1 at Bayreuth, 1876

"Die Walküre" Act 1 at Bayreuth, 1876

"Siegfried" Act 1 at Bayreuth, 1876

"Siegfried" Act 1 at Bayreuth, 1876

(The booklet accompanying the original Solti set of Die Walküre contains a reprint of an article first published in the September 1st, 1893 issue of “The Optical Magic Lantern Journal and Photographic Enlarger” which detailed how this technology had been used in Paris to present The Ride of the Valkyries.)

If you want to get a good idea of what those original productions must have been like, look no further than the production by Otto Schenk that played in the repertory of the Metropolitan Opera House for years. Yes, these are “realistic” sets, but somehow by striving to be as “real” as possible, the production only ends up emphasizing the unreality of much of the scenario. (I find it pretty unwatchable).

"Götterdämerung" at The Metropolitan Opera in Otto Schenk's Production

"Götterdämerung" at The Metropolitan Opera in Otto Schenk's Production

A similar problem afflicted Peter Hall’s 1983 Bayreuth production (which Solti conducted). Hall, one of the greatest theatre and opera directors of his generation, and his equally brilliant designer, William Dudley, fell seriously afoul of Bayreuth in-house politicking and the challenges of attempting to mount the cycle “naturalistically” by conforming fully to the composer’s original stage directions. (If you want to learn more about this debacle, seek out The Ring: Anatomy of an Opera, an excellent book by Stephen Fay and Roger Wood).

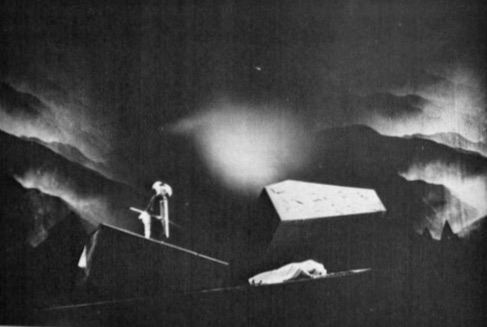

The genius of Wieland Wagner’s approach in his groundbreaking postwar productions at Bayreuth of both the Ring and Wagner’s other operas was to key primariliy into the ideas, the emotions and the characters more than into the settings. The sets and lighting were abstract, expressionistic, reflecting the inner life of the characters and the drama that was unfolding in the music. He turned the operas into works that existed most purely and vividly in theatrical terms: on the stage, at that moment.

Siegfried awakens Brünnhilde

Siegfried awakens Brünnhilde

Siegfried and Brünnhilde

Siegfried and Brünnhilde

Wotan and Brünnhilde ("Die Walküre")

Wotan and Brünnhilde ("Die Walküre")

Siegfried confronts Fafner the Dragon ("Siegfried, Act 2)

Siegfried confronts Fafner the Dragon ("Siegfried, Act 2)

Siegfried and the Rhinemaidens ("Götterdämmerung", Act 3)

Siegfried and the Rhinemaidens ("Götterdämmerung", Act 3)

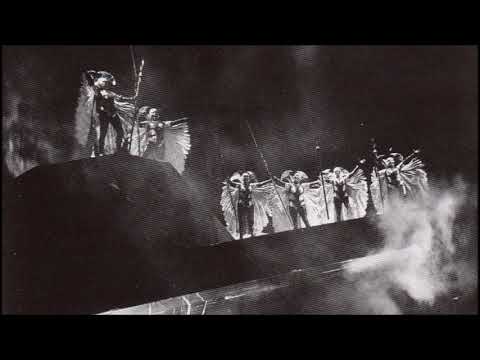

Brünnhilde and her fellow Valkyries with Sieglinde ("Die Wälkure, Act 3)

Brünnhilde and her fellow Valkyries with Sieglinde ("Die Wälkure, Act 3)

This approach was enormously influential, and resonated with changes in production styles beginning to happen in theatres worldwide. The production of the Ring that I saw unfold over a number of years in the 1970s at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, exemplified this more modern approach, and was highly acclaimed not only for the musical performances (led by Colin Davis in top form), but also the striking production which anticipated the psychological acuity of Chereau's 1976 centenary production at Bayreuth by several years.

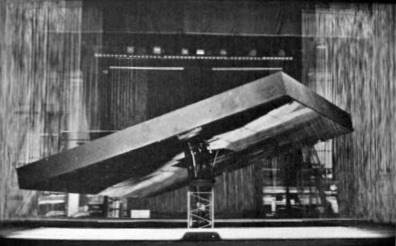

The brilliant set design was by Josef Svoboda, the director/producer was the great Götz Friedrich The regular stage was removed, and in its place there was a new rectangular platform which could move in any direction, often with actors on it, controlled by a vast central hydraulic piston.

The stage itself both contained the drama, yet also metamorphosed endlessly within that drama. That basic rectangular platform was always discernible throughout its mutations. It became its own unifying concept: the entire “world” of the Ring.

The stage itself both contained the drama, yet also metamorphosed endlessly within that drama. That basic rectangular platform was always discernible throughout its mutations. It became its own unifying concept: the entire “world” of the Ring.

For the opening scene of Das Rheingold it tilted upwards at a sharp angle, revealing the underside covered with mirrors, wherein were reflected the Rhinemaidens. The gold stolen by Alberich when he renounced love was within the central hydraulic piston.

For the mountain scenes in Die Walküre, vast slabs were added to the surface, and the edifice would circle and tilt at all angles as the action demanded.

The Ride of the Valkyries

The Ride of the Valkyries

Brünnhilde and Sieglinde in "Die Walküre"

Brünnhilde and Sieglinde in "Die Walküre"

In Siegfried a mass of hanging ribbons conveyed the claustrophobia of the all-enveloping forest where the hero lives.

"Siegfried" Act 1

"Siegfried" Act 1

Siegfried confronts Fafner the Dragon

Siegfried confronts Fafner the Dragon

At the end, when Siegfried climbs out of the forest to discover Brünnhilde asleep at the top of a mountain, surrounded by fire, the stage rotated and tilted as he climbed, eventually revealing her perched on its higher reaches.

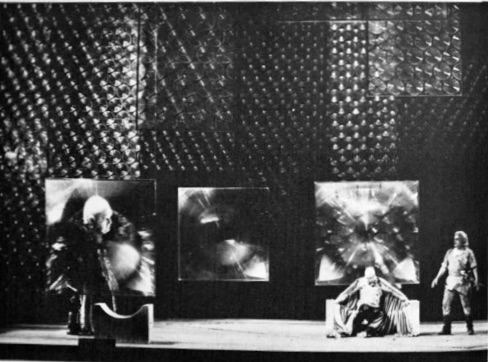

Part of the action of Götterdämmerung takes place in the Royal Palace of the mortal Gibichung, and revolves around the evil Hagen's various plots to kill Siegfried and steal the Ring. Set designer Josef Svoboda amplified the sense of paranoia and plotting with suspended magnifying glasses that characters would move around.

The evil Hagen (left) plots the downfall of Siegfried (right)

The evil Hagen (left) plots the downfall of Siegfried (right)

At the end of Götterdämmerung when the world basically goes up in flames and the ring itself is reclaimed by the Rhinemaidens amidst the cleansing waters of the Rhine, the evil Hagen - trying to grab the ring - leapt from the top of the platform into the pit beneath the stage, a drop of a good 30 feet or more - a thrilling effect. As the “Redemption by Love” leitmotif brought the opera to a close, the platform stage returned to its position at the start of Das Rheingold: flat and empty.

Along with this brilliant scenic realization, Friedrich did detailed acting work with his singers, so that every scene felt like real interactions between real people (with the richness of Wagner’s libretto, and the ever-evolving leitmotifs in the score fully supporting this approach).

A similar emphasis on scene work characterizes Patrice Chereau’s widely celebrated (though at its debut in 1976 roundly booed and reviled) centenary production at Bayreuth (with arch-modernist Pierre Boulez conducting). This production cast the action as a fable of the Industrial Revolution, depicting the power struggles between the classes. The opening of Das Rheingold was set at a hydro-electric dam, with the Rhinemaidens cast as “ladies of the night”.

Opening Scene of "Das Rheingold" (prod. Patrice Chereau, Bayreuth 1980)

Opening Scene of "Das Rheingold" (prod. Patrice Chereau, Bayreuth 1980)

Wotan and his fellow-gods were portrayed as out-of-touch aristocrats and capitalists at war with the lower echelons of society.

"Das Rheingold": The Giants Fafner and Fasolt seize the goddess Freia to extract more money from the Gods for building Valhalla (Bayreuth 1980, Set Design by Richard Peduzzi)

"Das Rheingold": The Giants Fafner and Fasolt seize the goddess Freia to extract more money from the Gods for building Valhalla (Bayreuth 1980, Set Design by Richard Peduzzi)

This production is now hailed as the birth of so-called Regietheater (or Director’s theatre). Filmed for television, I saw the BBC broadcast in 1980, and for me it remains the supreme filmed version of the cycle (and is available in a new Bluray transfer).

"Die Walküre" (Prod. Patrice Chereau, Bayreuth 1980)

"Die Walküre" (Prod. Patrice Chereau, Bayreuth 1980)

All of the above gives an indication of how Wagner’s Ring is in many ways the ultimate Rorschach test in opera, upon which directors, designers and ultimately audiences can project their own preoccupations, and from which they can draw their own conclusions.

This makes it the perfect candidate for a purely audio, non-visual, non-literal experience, where the listener can imagine their way into the scenario, inject their own sensibility and interpretation. The genius of the Decca Ring was to go beyond merely “recording” it. Culshaw and his cohorts created a new space in which the work could most fully unfurl and express its many layers of meaning, unburdened by a specific visual representation. This world that the recording inhabited came to be known as “theatre of the mind”, and that’s as good a way to describe it as any.

So how did Solti, Culshaw and the others do it? Well, they began by paying close attention to the details….

Continued in Part 2, covering the Decca recording sessions.....

.... and in Part 3, covering the various releases of the Decca "Ring", and their sound quality.