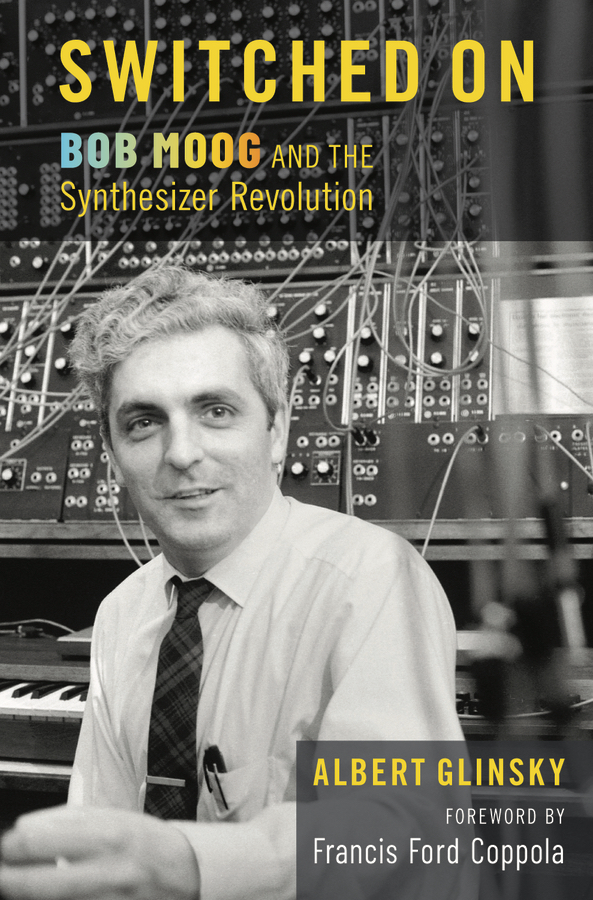

"Switched On: Bob Moog and the Synthesizer“

Albert Glinsky's Moog bio patches together the life of the inspired creator and his industry-defining brand

Before black turns to picture; before you see anything at all onscreen, the first thing you get to experience when you settle in to watch “Apocalypse Now,” is the sound of a Moog synthesizer mimicking the rhythmic chop of a helicopter blade. As director Francis Ford Coppola recounts in the forward to Albert Glinsky’s weighty tome on the life of electronics pioneer Bob Moog, “The Moog gave us the ability to roll sound effects and music into one.”

Switched On: Bob Moog and the Synthesizer Revolution runs through the 71 years of a life that helped tip the music world into the future just when the sonic innovations of the sixties seemed to have almost run their course. Near the end, with his legacy firmly in place, the great man could roll around Asheville, North Carolina largely unrecognized in his battered and hand-painted Toyota Tercel. The legendary engineer, who was outwardly quiet and serious, was just as comfy yanking organic tomatoes from his back garden as he was tuning his chakras with a local healer. What we find then across these nearly 500 pages is the outline of a man whose life was as nuanced and complex as the tangled nest of wires that ran across his famous machines.

Moog often said that he “slipped backwards on a banana peel” into the music instrument business, but what Glinsky makes clear in the early portion of his book is that had you tried, you couldn’t have designed a more likely synth maker. Force fed piano lessons by his mother, his fun time was mostly spent in the family basement building electronics from the schematics he found scattered throughout his nerdy science magazines. He demonstrated his first theremin during his junior year at the Bronx High School of Science, and at the age of 19, wrote up his own design for the spooky sounding sci-fi instrument in the January 1954 issue of Radio and Television News.Moog was essentially on his way.

Driven by a narrative that’s built on workman-like research and personal correspondence, we watch Moog go from the Cornell University campus where he pursued his Ph.D in physics, to a truly promising young man with a wife in waiting who was able to maintain a side hustle selling theremin kits from his home. The first real hint we get of the future comes some 70 pages deep, when Glinsky gets to write into the picture composer and Hofstra professor Herb Deutsch. He and Moog came across one another at a music association expo in 1962, and that meeting would yield the spark that led to Moog’s first primitive synthesizer. After bouncing ideas off one another, Bob came up with a rudimentary musically playable device that he would dub the “Abominatron.”

From that simple prototype to the small amps and the titanic synths he would go on to build in his tiny factory in nearby Trumansburg, NY, Glinsky captures the pains and aspirations of getting Moog’s business off the ground through the passionate letters the young entrepreneur sent to friends and family – particularly to his aunt Florence, who lent an ear and the occasional infusion of cash to keep her nephew’s spirits up. But while he might have come across as grim or even desperate in some of those letters, publicly he kept the faith.

“I see a full-blown fad in pop electronic music about to erupt.”

But the author is careful to point out that Moog wasn’t working in a vacuum. Other soon to be well-known manufacturers, like Don Buchla (1937-2016) were also plying their circuitry in the service of futuristic sound. These detours from the main throughline are an important aspect of the portrait that Glinsky has chosen to paint—a world where electronic innovation seemed to be crowding in at every turn. Who got there first was only so important. Because even after a young Wendy Carlos took on the challenge of recasting some baroque masterworks via her sizeable modular system for 1968’s revolutionary Switched-On Bach, the Moog name was out front only momentarily.

In some ways the book delivers what is almost a masterclass in how “not” to run a cottage industry. With worldwide orders pouring in for his synthesizers, you might expect Moog to have been neck-deep in cash. But that was far from the case. It took untold hours for the locals he hired to solder together components, and there was no real way to speed up the process. That, coupled with the fact that Moog liked to work one-on-one with artists, designing systems customized to the specific needs of his clientele created a certain amount of churn. Not even the arrival of the iconic Minimoog Model D, which was the brainchild of Moog’s bright young engineering staff, could salvage Moog’s story from becoming a tale of unfriendly investors and loads of corporate woe. Dejected and reduced to employee status, Moog watched his brand name recognition precipitously sink and not to be revived until decades later.

Glinsky, who also chronicled the life of Moog’s hero Leon Theremin, brings just as much detail and veracity to these pages as well. His take on Moog as a brilliant and inspired creator is not lost over the immense scope of the text. But the part of the story that shifts Moog’s life into the iconic—beyond Switched-On Bach, and past the Prog Rock heyday (when the company could have probably shipped a sequined cape with every keyboard that went out the door…), isn’t as well attended to. The stories of the Synthpop, Electro and Post-Rock generations that resurrected and eventually kept the Moog name alive don’t rate as much word count as the financial woes that cost him his trademark. All biographies in a sense are a kind of filet, and Moog’s story would have been more engaging if his story wasn’t so front-loaded.

But there are moments that Glinsky highlights here that do pack in some gristle—like the very human story of the birth of Moog’s son Matthew, or the compassionate speech he gave to the students at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia in 2003 as they handed him an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts. As the author purposely points out, Moog still had the presence of mind to realize that what mattered most about the instruments he had created were the people driving them. The human connection to sound was the key as he reminded the audience who were about to come of age in the 21st century:

“We’re going to need you to hose down the psychic dust that technology is likely to create in the future. We’re depending on you to remind us what life is all about.”