Ry Cooder & Taj Mahal Pay Tribute To Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee's Folkways LP Get On Board

And Have A Great Time Doing It!

Ry Cooder, in 1959, when he was 12 bought a copy of a ten inch record on an odd label with an amateurish paste-on cover and mimeographed liner notes tucked inside. The record was Get On Board by Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, two middle aged Black men who had been playing blues for Black audiences for more than two decades, but now, probably to their own surprise, were becoming popular with young white people. Cooder began listening and woodshedding and we know the rest of his story.

Now in 2022, Cooder with Taj Mahal has released Get On Board: The Songs Of Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee. Two old guys playing and singing the songs of …who? Why? Where’s the “high concept”? It’s not like Sonny and Brownie ever met the Devil at the crossroads and gained very posthumous Grammys, gold records and forever hip cred. Maybe Cooder explained why, when he wrote in the notes to the album, “Get On Board was originally released at the height of the McCarthy era: bad times + good music—always a winning combination.”

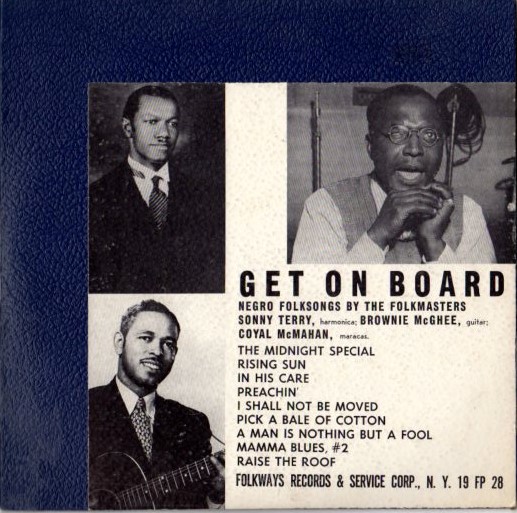

Get On Board was an important and pivotal album in the long and varied careers of Sonny Terry (1911-1986) and Brownie McGhee (1915-1996). While credited to the “Folkmasters,” it was the first Terry & McGhee LP and the first recording of the duo marketed to the white folk revival audience.

Recorded in 1951 or 1952 for Moses Asch’s Folkways label, it is testament to Asch’s adventurous, if not downright eccentric, recording policy that Get On Board was also the first commercial LP album of contemporary recordings of Black rural music. Yes, Folkways was once in the commercial record business—sort of. The Folkways catalog when Get On Board was issued included, not only the now famous, but then known only by the ultra-hip, names like Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly, but also thirty-five ethnic music albums (Rumania, The Hebrides, Uzbek, Armenia, The Ukraine etc.) as well as recordings of Scottish bagpipes, cowboy ballads, cantorial singing, folk tales from Indonesia, dance-a-long rhythmic exercises (proto-aerobics?), exotic dances (No, they couldn’t have been that kind!), meetings of The James Joyce Society and logger-men songs (obviously, a huge influence on Monty Python) Something for everyone? More like something for a few.

Folkways’ market was urban, collegiate, leftist intellectuals and hipsters and thus the perfect label to record and market Black artists performing folk-blues to white young people. Folkways didn’t do a lot of promotion, but the labels’ reputation for quality and integrity and Terry and McGhee’s constant gigging at hootenannies, parties, folk clubs and concerts made the album a good seller and it was still being pressed in the mid-60s.

Guitarist, McGhee and blind harmonicist, Terry met playing on the streets of Burlington N.C. in 1939 and formed an off again, mostly on again musical partnership that lasted for over forty years. Terry had started recording in 1937 as a sideman for the extremely popular bluesman Blind Boy Fuller and made several dozen records with him before Fuller died in 1941. Terry’s harmonica virtuosity and energetic “whoopin’ hollerin’” stage presence attracted the attention of John Hammond which led to Terry appearing at the 1939 From Spirituals to Swing concert. As it did for Bill Broonzy, the concert introduced Terry to a new audience and the opportunity to perform and make records for the more lucrative white market. In 1940, McGhee began a successful career recording blues records for the Black jukebox market.

Throughout the 1940s and early 1950s, Terry and McGhee with Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly played live shows and recorded folk songs, spirituals and what were even then, old blue songs for the white folk-blues audience. At the same time, together and apart, they were making rocking up to date blues/R&B juke box records for Capitol, Savoy and smaller labels. McGhee, on his records without Terry, sounded completely unlike his folk blues incarnation, playing electric guitar backed by jazz musicians while he shouted the blues in the urban style of Joe Turner and Wynonie Harris. Terry became well known even beyond the folk-blues scene when he appeared as a harmonica playing member of the cast of the musical Finian’s Rainbow which ran on Broadway for more than two years.

Get On Board was a shrewdly calculated decision by Terry & McGhee to make a record that would appeal to their growing white folk revival audience. It was a ten inch LP (a 33 rpm microgroove format that was phased out by universal adoption of the 12 inch LP in 1955-1956) and only had a total running time of 22 minutes. The nine songs show that Terry and McGhee had, already at this early stage, made a clever assessment of the type of music that the white audience wanted to hear. Ry Cooder summed it up well,” ‘Folk Blues’ meant music straight-life folks could feel good about: acoustic instruments, easy rhythms, family-man lyrics.”

The superb playing and singing of Terry and McGhee in the unique style that was to make them popular and successful for decades is fully apparent on Get On Board. Both were virtuoso players. McGhee was one of the greatest acoustic guitarists, incorporating unusually sophisticated chords and jazz influenced rhythmic subtleties into a hard picking but still delicate style that retained a rural flavor. Guitarists of the caliber of Dave van Ronk and Bert Jansch credited him as a primary influence. Terry was a master of unamplified country blues harmonica with an inimitable vocalized, hard swinging, near jazzy sound.

The most innovate aspect of Terry and McGhee’s music was their rhythm and time feel. Unlike the heavy, stomping country dance rhythms of Leadbelly and other rural blues musicians, Terry and McGhee played with a lighter, leaning forward, swinging beat that was their version of Black Swing Era jazz rhythm. Both were excellent singers with bluesy and southern sounding but not eccentric or rough voices and clear diction. Together, their voices achieved the hard to define and harder to achieve effect of melding but sounding different together. Live and on records, they conveyed a loose, informal, front porch picking mood that was much different from the intensity of Leadbelly or the slick professionalism of Josh White and Bill Broonzy.

Two of Get On Board’s songs—"Midnight Special” and “Pick A Bale of Cotton” are folk songs associated with and made well known by Leadbelly. “Pick A Bale of Cotton” is patterned on Leadbelly’s solo version but the swing feel of Terry’s lead vocal and McGhee’s guitar make the rhythm so infectious, that inappropriately, a song, about back breaking labor, becomes an exuberant dance number.

Two more songs----“Rising Sun” and “A Man Is Nothing But A Fool” are McGhee composed blues. On “Rising Sun” (not “The House of the..”) he accompanies his vocal with chords in an easy rocking swing feel while playing at the end of the vocal phrases, slightly differently every time, a melodic theme, that is a bit similar to “Key To The Highway.”

“Raise A ‘Rocus Tonight!” (mistitled “Raise The Roof” on the front cover) is a 19th century Black song. Its catchy melody and good time lyrics made the song a favorite, not only of 1920s Black jug bands but also of early 1960s collegiate folk groups. Both Bette Davis and Debbie Reynolds sang the song in Hollywood movies. Terry and McGhee play it up tempo and powered by McGhee’s strong rhythm guitar, it’s folk-blues rock ‘n roll.

“In His Care” is a Black gospel song recorded by Ry Cooder on his 2018 Prodigal Son album. “Preachin” is not a song at all but a one minute snippet of semonizing. Both pieces feature vocals by the maraca shaking third “Folkmaster,” the mysterious Coyal McMahan whose smooth vocal style is like that of a pop singer or an urban preacher. The only information available about him is that he was a cast member of Finian’s Rainbow, possibly at the same time as Terry which could explain his presence on the record. Get On Board and two other songs recorded in 1952 with Terry and McGhee seem to be the total of his recordings

“Mama Blues #2” is a Terry virtuoso harmonica imitations novelty piece of the type that was a crowd-pleasing part of the Terry & McGhee live set throughout their career. “I Shall Not Be Moved” is a 19th century Black spiritual which became associated with labor union strikes and protests in the early 1930s, later becoming a “freedom song” during the 1960s Civil Rights movement. Terry’s harmonica playing on the song masterfully alternates hard charging rhythm licks with melodic phrases that interweave with the vocals of McGhee and McMahan.

After the success of Get On Board, Terry and McGhee, continued to record R&B and blues but increasingly devoted themselves to their folk-blues career. By 1960, they were recording only in the folk-blues style and had appeared on Broadway and toured in the play Cat On A Hot Tin Roof, been in a motion picture and on Harry Belafonte’s CBS TV show, performed at the Newport Folk Festival, toured the U.K. and made a U.S. State Department tour of India. For the rest of their career together, they were the most well know Black acoustic blues musicians and until the late '70’s, they toured constantly, playing to predominantly young white audiences.

Taj Mahal and Ry Cooder’s Get On Board, despite the title and the cover similarity is not a remake of Terry and McGhee’s Get On Board. Only three songs from the Terry and McGhee album are performed by Mahal/Cooder on their Get On Board. Mahal and Cooder have recorded a tribute to Terry and McGhee but not a copy or imitation like those dreaded “tribute bands.” “To senselessly try to put their ‘lightnin’ in a bottle’ would have served no one!” in the words of Taj Mahal. What Cooder and Mahal do on Get On Board is put their own lightnin’ in the bottle of Terry and McGee’s music.

They let us know what they’re up to right away on the first track, “My Baby Done Changed The Lock On The Door.” Mahal begins singing and the guitars and the drums fall into a very un-Sonny and Brownie style 70s boogie rock groove with the drums playing a heavy backbeat. After the second verse, Cooder plays a wild slide guitar solo with a tone so thick and funky it’s laugh and shake your head, outrageous. He takes the tune out with more stunning slide over that just won’t quit groove.

“Midnight Special” is done in an unusual seven bars and a pick up arrangement with drums and percussion playing polyrhythms. Cooder’s lead vocal has a beautiful relaxed feel. He’s a much better singer now than he was in his Reprise days. Mahal is not the virtuoso that Terry was, but his harmonica playing between the verses is hip and funky. The background vocals are a bit out of tune but then so were Sonny and Brownie’s.

“Hooray Hooray” has a loose, making-it-up feel. Taj is ready to end his harmonica solo but Ry tells him, “Go ahead” and he plays another chorus. The song has a great beat—a lowdown cajun flavored groove that is just dirty in that special can’t help feeling it, hip shaking way. Joachim Cooder’s drumming is light and doesn’t take up a lot of sonic space but his groove is thick. Throughout the album he minimizes the blues cliché rhythms-shuffles and boogies and plays his own style with bits of world beats-African, Cuban, Caribbean, soul, funk and even ambient. His contribution to the success of the music is every bit equal to that of the masters he played with.

“Deep Sea Diver” features Taj on piano and foot tapping with Ry on guitar and singing lyrics which barely qualify as suggestive, “I got a stroke and I can’t go wrong, I can dive to the bottom, ‘cause my wind holds out so long.” Taj’s piano is a bit rough but his beat is strong. Ry sounds like he’s having a lot of fun and ready to crack up at several points.

“Pick A Bale of Cotton” is played at about the same tempo and with the same vocal arrangement as the Terry and McGhee version but the drums play heavy on two and four which makes the tune seem almost like a rock number. Taj blows the lyric in the second verse, laughs and they continue. Can’t let a mistake stop the fun.

“Drinkin’ Wine Spo-Dee-O-Dee” is played over a laid back, swampy Caribbean/African rhythm. Taj’s lead vocal is the perfect mix of sly humor and half in the bag. He even adlibs “Boones Farm!” (Oenophiles, please send your “Boone’s Farm isn’t really wine” corrections direct to Taj.)

“What A Beautiful City” has Taj’s aged prophet voice trading verses with Ry and they each bring their own soulful sound. Mahal’s harmonica is very vocal and sounds a lot like Sonny Terry on this tune.

“Pawn Shop Blues” is a Ry Cooder solo feature and he plays with that mixture of relaxed intensity, propulsion and ease that only the greats possess. The slide guitar on this track is gorgeous. Though he refers to himself as “Brownie,” Ry’s vocal, to my ear, is more similar to Lonnie Johnson’s singing.

“Cornbread, Peas, Black Molasses” is a country style tune and Ry’s vocal sounds a lot like Levon Helm. Appropriately, Joachim Cooder plays a Levon-like drum groove on this song that is a masterpiece of no show off virtuosity.

“Packing Up Getting Ready To Go” is the ringer track on the album. It has backing vocals by the contemporary soul group the Ton3s and there is a studio compression effect on Ry’s lead vocal. The track reminds me of '80s Tom Waits with its mysterioso, ominous vibe and simple three note funk groove.

On “I Shall Not Be Moved” Taj and Ry sing the spiritual together and while they have some intonation issues, the voices blend well and they sound sincere and impassioned. They remember the song being sung by civil rights workers at sit-ins before they were hauled off to jail. The drums and guitar lock tight into a medium tempo stomping beat which is much different than the up tempo swing of Terry and McGhee’s version.

Cooder and Mahal’s Get On Board sounds so unlike most 2022 music that it seems like it was intended that way to make a statement. The album was recorded near live in Joachim Cooder’s living room with what appears to be from the photos and the sound, minimal miking. Overdubbing was kept to a minimum—some bass and slide guitar and the occasional extra voice on choruses. The vocals are obviously not autotuned. No, more than obviously. They are in your face—“What’s the matter, you can’t handle the truth?”—not autotuned. Intonation issues are all over the album. Taj and Ry make mistakes or semi-mistakes when playing. Sometimes, it’s clear that they’re not sure how to end the tune, or when the solo will end or even how the lyrics or the arrangement go. Does any of this make a difference? I say “No, because feeling and honesty are what matter most in music.” This album has plenty of both and plenty of the next most important thing in music—joy.

The recording quality of the Cooder/ Mahal Get On Board is very good and very honest. If someone gets to close to the mike or plays a little too loud, you hear it. The soundstage is not super wide or deep. The bass is not bottom octave low. The recording has a hint of digital and lacks analog demo record air and low level detail. The most important news is that the voices and guitars have in the room human presence. Dynamic range is excellent, no brick walling, so that tiny rhythmic subtleties are captured making the rhythm groove so strong and powerful you can get lost in it. Cooder and Mahal, while making this album conjured up fun, humor, warmth, love for and connection to the great tradition of American music and the recording captured it all. Good music for these times. Thanks, we needed that.

My copy of Taj and Ry’s Get On Board was nicely pressed and played quietly without significant flaws. The LP can be purchased from all the usual sources. The Terry & McGhee Folkways ten inch Get On Board is an excellent recording, minimally miked with a beautiful early '50s tube midrange. Clean copies can be purchased for about twenty dollars. The Smithsonian Institution, now owner of Folkways, has a digital download available.

Copyright 2022 by Joseph W. Washek

All rights reserved