Lansing's Lost Legacy

the dawn of hi-fi—The Lansing Iconic

***all names of those involved and living have been changed for privacy***

My involvement in this story begins in 2011. While messing around at Community College, I took a basic radio production course for an easy A to help my mediocre GPA. As it turns out, the class was taught by a legend in the audio community, a fellow named Bruce. On the first day, we had already discussed tape machine flux values and EQ standards, which was well outside the syllabus. He was quite surprised that someone with an audio background would wind up in such a class. I took full advantage of his experience, knowledge, and kindness and got all I could out of the course. After one class, he pulled me aside and mentioned that I should attend a local Audio Engineering Society meeting happening that Sunday evening. The rest of the class was about half nice people just looking for an easy course, and the other half of the people just didn’t have the rabid technical interest I did. He didn’t feel that the local AES chapter was right for anyone else there. (My words, not his!).

So, I went to the meeting. I felt out of my league, didn’t understand the presentation given, or know anyone there except my professor. I had planned to slink away quietly after dinner, and continue on the path I had made for myself. The meeting was held in the basement of a restaurant I had never been to. Nearing the end of the dinner, my bladder informed me it should be emptied soon. Not wanting to draw any attention to myself, I waited until the bill came, I paid, and I started to make my way through the milling throng to the stairs up to the main level. On my way out, the president, Stuart, stepped into my path and introduced himself. He wanted to know who I was, where I was from, and what brought me to the meeting, as he noticed I was new and looked a bit lost. As best I could, I described being taught by Bruce at the community college, our talks, and his invitation to come to this meeting. Upon hearing I was into “old stuff”, he got visibly excited, and started to talk about tape machines, vinyl cutting, microphones, and what he did….all the time I was just trying to hold it together and not explode! We were having a remarkably nice chat, but I quickly let him know that I absolutely HAD to head out, and he insisted that I come to the next meeting! I agreed, and made my exit, and I don’t think I’ve ever run up a flight of stairs that fast, and made it in time to the restroom. Whew!

Anyway, now that I felt that I’d made a new friend, and despite being a novice at the more advanced and modern aspects of audio, my presence was wanted. Vowing to attend every meeting I could, I did for almost a decade. COVID stopped in person meetings, and by the time they resumed, I had started a new job that keeps me working while they happen. C’est la vie.

I became better friends with Stuart, and he realized that I like preserving history andcollecting ‘cool old stuff’. I have to move a bit of it to keep my hobby rolling, but I really do care about the gear and its backstory more than any monetary value. So, Stuart started giving me things that he had been saving in his “someday” pile, and putting me in touch with others who also wished to see their treasures cared for by someone who appreciates history. We have remained good friends, and I have been able to source him some obscure goodies he’s searched for.

Fast Wind to March 5, 2022

I get a text, with a photo, “On another note, George has an old Lansing speaker that Mr. Harrison got from James Lansing himself… I’m not sure I have the space for it, but it is really cool. I haven’t done any research on it. Interested? Only the speaker from this pic”.

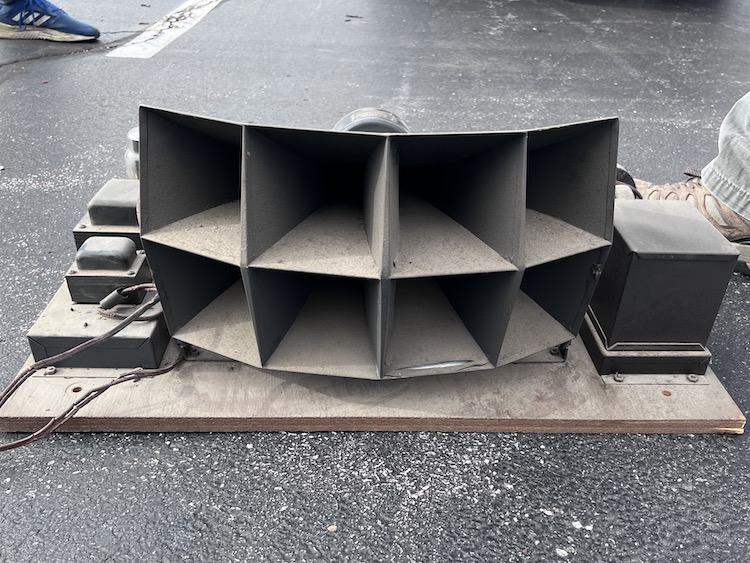

I immediately asked how much it would be, not recognizing the speaker from anything I’d ever seen before and having to weigh the cost to acquire vs. what the item was AND how much space it takes up. My house is already full. He said he didn’t know, and that he’d get back to me. Instead of a price, I got a phone number for the owner, and I arranged to go over and take a look in two days’ time. So, I loaded my moving dolly up, and headed down to the appointed address. Turns out, the speaker was in a media duplication facility, and the owner was their chief technician (I’m not certain of his exact title). The speaker had been in his office for a number of years, serving as conversational decoration. My first thought was “Oh, it’s BIG!”.

The one photo I had seen made judging scale a bit difficult, and it was far more imposing in person. We shook hands, I sat down, and he told me the following story, which I will paraphrase here: James Lansing gave a presentation with his speaker at the First Audio Engineering Society conference at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel in New York City. On his way back to California, Lansing, being an imbiber of alcohol, ran out of money, and was forced to sell his demonstrator model in order to make it home. He made it to St. Louis, Missouri, and the speaker was purchased by Bud Harrison, owner and founder of Technisonic studios. The speaker was then used as the main monitor in the mono era and became the AM Radio and TV broadcast check speaker in the stereo era and was in use in various positions until the late 1980s.

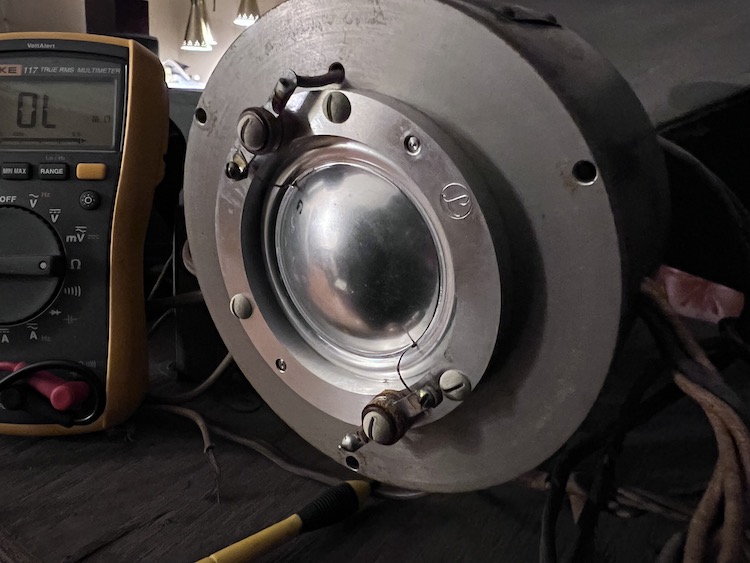

At the time I heard the story, I was not familiar enough with the timeline of Lansing to understand which parts may or may not be true, and accepted the tale at face value. He then turned the speaker around, and showed me the crossover network, horn driver, and power supply. I hadn’t seen anything like it in person! We both marveled at the low serial number of the driver, and the crossover serial number being Z0. It was quite clearly pre-Altec and pre-JBL. George said it has not been used in many years but was under the impression that all it would need was a power cord replacement and would sing again. I was then given a wonderful and mind-boggling tour of the duplication plant, encountering devices I have never seen, such as laser beam recorders, and learning far more about the digital disc creation process than I had ever dreamed of knowing.

As the visit drew to a close, I finally brought up the big question, which was: “How can I take the speaker home today?”. George told me that the speaker was really only offered to his friend, who he had worked alongside for decades at Technisonic studios, and he really wasn’t ready to give it to anybody else yet. I even offered some money, and that didn’t persuade him. So, I bid my farewell, assuring him that I would happily provide a home for such a neat piece of audio and St. Louis music history at any time in the future. That is where I thought the story would end.

I was so certain that I would be taking the speaker with me, that I neglected to take any photos! So, I texted George for some detailed pictures of what we could see. He obliged, and I started the research project.

My first few ‘usual suspect’ vintage horn speaker collector friends had never seen such a thing, one of which even told me that I had misinterpreted details, as I described what I had seen. I believe his direct quote was “the only set up like that was the OG Lansing field coil rig, and those just don’t exist“. I had, of course, seen the regular Iconic in my research through the years, tracing the history of High Fidelity, but never dreamed that I would encounter one in person. Finally, a long time online friend in Arizona said that he might recognize the cabinet design, and he would do some digging. A couple of hours later he sent me back the Lansing Manufacturing Bulletin Number Four catalog page that has both the standard early Iconic we know about, as well as a highly similar cabinet, called the “Model 810 Loud Speaker Console“. It was clearly a close match, with only some minor outer trim differences which could easily be attributed to the prototype legend, or a minor production variant. My friends and I were floored, because no one I talked to had ever seen such a thing in real life. There were no photos on the Internet, no discussion, and it seems that the speaker was never built in any large quantity. It appeared that this was a unicorn.

For such a well-documented history, I knew an addition to the canon like this had to be special. So, I decided to try and put the timeline together to prove the legend. It quickly became apparent that there were a few inconsistencies in the story as related to me. The Lansing Manufacturing Company was purchased in 1941 by Western Electric to form Altec-Lansing. Five years later (to the day), Lansing left to found James B. Lansing Sound, Inc. (which we now know as JBL, and is under the auspices of Samsung). Being a member of the Audio Engineering Society, I was able to go into the online archives and download the exhibit list for that first gathering. The first Audio Engineering Society ‘Audio Fair’ was October 27-29, 1949, and at the Hotel New Yorker. The list also documented participants from each company that exhibited, and Lansing‘s name is nowhere to be found, other than the company name “Altec-Lansing”. So, there was little reason to bring a then 12 or 13 year-old speaker from two companies previous to an exhibition. There is also the small problem that Lansing himself had tragically ended his own life on September 29, 1949.

For such a well-documented history, I knew an addition to the canon like this had to be special. So, I decided to try and put the timeline together to prove the legend. It quickly became apparent that there were a few inconsistencies in the story as related to me. The Lansing Manufacturing Company was purchased in 1941 by Western Electric to form Altec-Lansing. Five years later (to the day), Lansing left to found James B. Lansing Sound, Inc. (which we now know as JBL, and is under the auspices of Samsung). Being a member of the Audio Engineering Society, I was able to go into the online archives and download the exhibit list for that first gathering. The first Audio Engineering Society ‘Audio Fair’ was October 27-29, 1949, and at the Hotel New Yorker. The list also documented participants from each company that exhibited, and Lansing‘s name is nowhere to be found, other than the company name “Altec-Lansing”. So, there was little reason to bring a then 12 or 13 year-old speaker from two companies previous to an exhibition. There is also the small problem that Lansing himself had tragically ended his own life on September 29, 1949.

Now, Mr. Harrison was an individual not known for making up stories or being anything but precise, according to all who knew him. I decided to investigate what other organizations related to audio may have had dealings or meetings in New York City in the late 1930s. One likely candidate might be the Acoustical Society of America, who has documented that they had NYC meetings in 1936, 1938, and 1940. Their intervening-year meetings were in Chicago, which could also be a viable option. It seems reasonable that “Acoustical Society of America” or “ASA” could have morphed into “Audio Engineering Society” or “AES” through five or more decades of retelling. I will be reaching out to the Acoustical Society of America to see if any existing meeting notes, or, even better, photos exist from this time. It would be gratifying to be able to prove that Lansing and this speaker were there. The narrative as related to me may remain unprovable with the documents that exist today, but I will try! If you, the reader, have any suggestions, feel free to let me know.

The Origins of Fidelity (condensed)

Let’s take a step back in time, and examine the circumstances which birthed the Lansing Iconic. In the early 1930s, talking pictures were taking the world by storm, but the earliest generations of sound systems had numerous and obvious failings which caused complaints from both the public, as well as creators, studio owners, and theater owners. Distortion and a lack of frequency bandwidth hampered the sonic experience. As systems tried to expand on existing technology, a unique problem began to develop: Many of the early horns were exceptionally long, with effective path lengths (the distance between the driver and mouth) of upwards of a dozen feet, and often curled into a snail-shape for compactness. When engineers tried to add extra woofers and/or tweeters to the system to extend the frequency response, they ran into the problem of percussive sounds, like tap dancing, doubling due to the distance difference between drivers and an overall smearing of the sounds created by the system. One tap went in, two taps went out. Enter: John Hillard of MGM and Dr. John Blackburn. Blackburn and Hillard had already met and discussed improving the theatrical audio experience as early as 1932.

In 1934, with the depression in full swing, Blackburn was offered a job at the Lansing Manufacturing company, and brought his new employer into the project which he and Hillard were exploring. Previously, Lansing Manufacturing had primarily built radio speakers of a conventional cone type. All those involved wished to improve the standards for theatrical reproduction, and quantify the levels of time delay required to ensure acceptable driver blending. Their solution, developed together with audio luminaries such as Harry Olsen and Robert Stephens, was the Shearer Horn. It was a massive wall-sized monstrosity which boasted a 50hz-8khz +/-2db frequency response and a time delay difference of less than 1 millisecond (about a foot, in terms of distance) between woofer section and multicellular horn. This was a revolution from what came before and was completely adequate to reproduce the Academy Mono optical soundtracks in use on film at the time. This speaker caused a revolution in film sound reproduction, and it was apparent that a smaller version was required for limited space applications and monitoring.

The first attempt at “smaller“, became the “Monitor 500”, which was still several feet wide. For living rooms, small control rooms, and other confined spaces, a smaller device would be required. After research and development, the Iconic system was born. This was the progenitor of thousands of “15 inch vented woofer and a horn“ designs that were to be common in the loudspeaker industry for the next 40 or 50 years, particularly in the high output/high sensitivity arena. A variant of their woofer design was created, called the 815, suited for a vented box, and a new “small format” high frequency driver, the 801, was introduced. This driver continued to be produced with few fundamental design changes, other than a conversion to permanent magnet in the mid-1940s and built by Altec and their subsequent companies as the 802, until approximately 1990, At JBL, the DNA became the 175, of which variants are still being made today, and is my favorite classic JBL compression driver design. Speaking of permanent magnets, let’s discuss the flux making technology that makes this speaker different from many other speakers.

Why is this Magnet different from all other Magnets?

Before the invention of Alnico V, during World War II, loudspeaker manufacturers that wished to have a higher magnetic flux in the gaps of their speakers yet retain a commercially viable product would have to use an active electromagnet to generate such fields. Existing magnet technology was not suitably advanced for a passive magnet of reasonable size to create the sort of magnetic field required for large, high sensitivity, higher fidelity loudspeakers. This active magnet technology was called “field coil“ and utilized either an external power supply in order to generate the voltage required, or oftentimes, in the case of most vintage radios, the coil became part of the power supply choke. As an aside, this is why I believe many vintage radios wound up missing their 12 or 15 inch speakers, and the person who removed them might’ve been sorely disappointed upon connecting to the voice coil and getting little to no sound. The thrifty individual might then dispose of the driver, thinking it wasn’t working. The Iconic uses 220 volts DC, provided by an external power supply. Be very careful-these voltages can kill you if you don’t know what you are doing!

Thus, with the addition of a 800hz 12db/oct crossover (likely with some horn padding-I don’t have a schematic and have not opened the sealed steel can in my Iconic) and a small Stephens-designed sectoral H808 horn, the Iconic was born. Having a specified frequency response of 40hz-10khz +/-2db, it provided a far more transparent window into the signal than any other commercially available system of the day.

The Iconic has gone down in history as the most influential loudspeaker ever produced, and while I think that its descendants often have many flaws when viewed from a modern audiophile perspective, the Iconic was the first in a line of history-makers. JBL even accepted a TEC Award for the Iconic in 2011! I love trying to quantify history, but my audio evolution has shown me that I can’t tolerate the rough edges, inaccuracies, “voicing”, and general shout inherent in so many classic speakers that have descended from the Iconic and other early designs. I’ve heard innumerable classic Altec and JBL products from the Altec 604C, Voice of the Theatre variants, JBL Paragon, Altec Model Nineteen, to the dynamic driver models like the JBL 4311, L250ti, L150, and dozens of others. While I can appreciate what they hold a place in history and often are some of the most beautiful speakers ever built, the actual sound most of them produce makes me want to run away as fast as my legs can carry me! The son of a dear departed audio friend once termed his father’s VOTTs “the largest icepicks I’ve ever heard”. I didn’t disagree.

Getting into mid-level audio as a teenager, I sold my Goodwill find JBL 4311s a week after finding New Large Advents. The winner in the comparison was clear. I have enjoyed the small JBL 4301B and beautiful marble-topped JBL C56 (with the LE14A/175DLH driver load-a descendant of the 801)! The more modern LSR series of monitors are a wonderful budget option, too.

These classic loudspeakers have for me so often a “don’t meet your heroes” type of listening experience, once modern high fidelity expectations are in place. That’s not to say that I haven’t enjoyed my time with other classics-the RCA LC1A (MI-11411) and LEE Catenoid both offered surprisingly entrancing and enjoyable listening experiences. At the time I heard the RCAs, I was unable to purchase them, while the LEE was saved from a thrift store half a continent away by an eagle eyed friend, and stayed in my collection for a number of years. It would still have a place of honor, except… A friend was building a full tube mono National system following a lab accident which claimed half his hearing. While chatting one night, he casually mentioned that he’d been looking for a decade trying to find a LEE Catenoid. It was the speaker sold with the National tube rig, and he’d been unsuccessful in acquiring one. He had also heard positive reviews from those who had heard one. A rapid succession of messages followed, and I was convinced to pass the speaker into his care. I got his stereo record collection, and a few other goodies, and the speaker has a permanent and loving home. He was thrilled with the sound-as was I! It remains the best-integrated multi-way 1950s speaker I’ve heard. I also surprised him with a few boxes of mono pressings I was unlikely to listen to again, which seem to have filled some gaps in his collection!

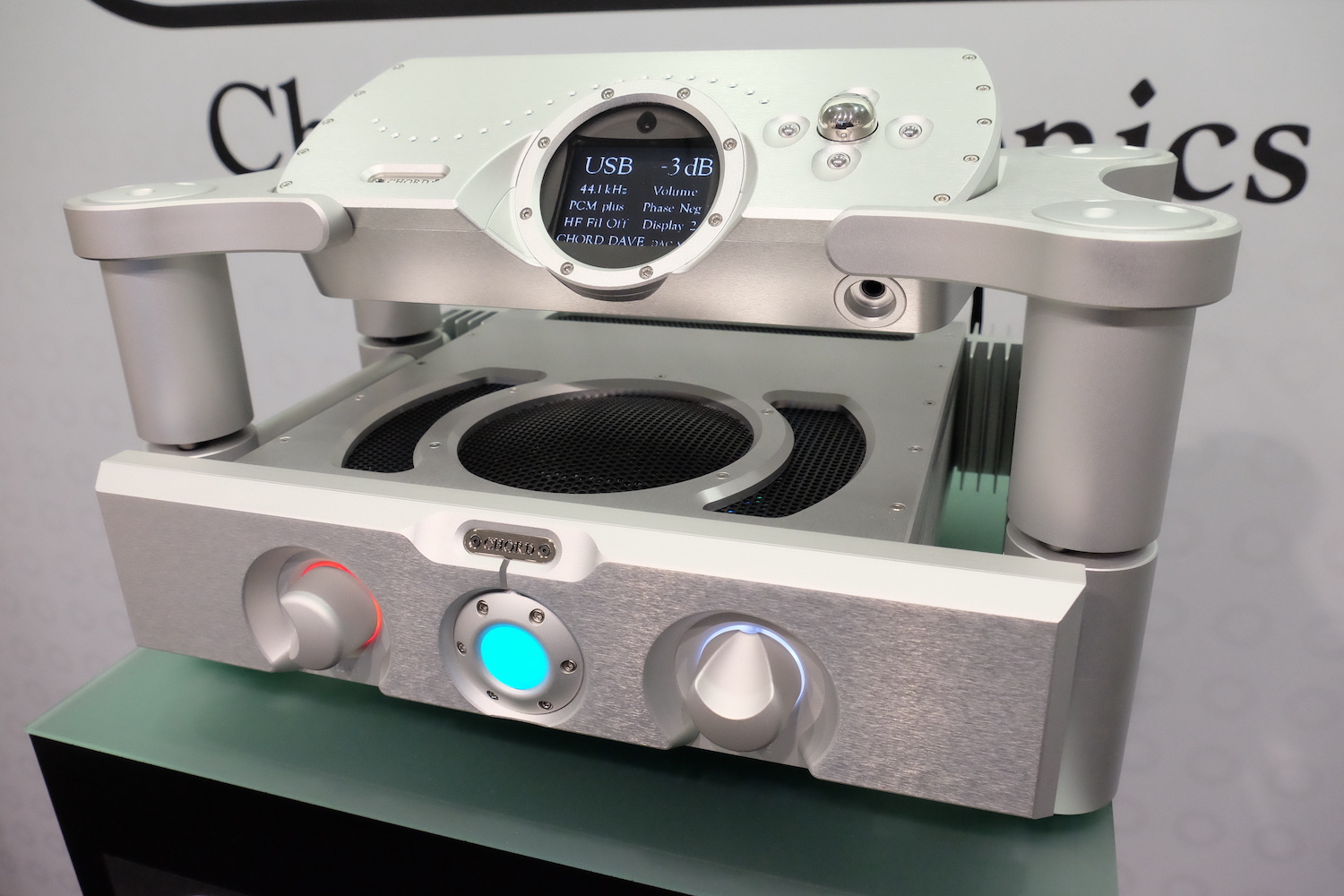

To reign this tangent in check, I’ll summarize that my taste typically runs to the “East Coast” sound when it comes to classic loudspeakers. I was quite curious about hearing the Iconic, and concerned at the same time. Internet lore claims that they’re a different experience than the later descendants, and perhaps that may be true. A friend often jokes that I wait so long to listen to new classic gear finds because the moment I do, they go back up for sale, unless they have interesting history attached! He’s usually not wrong. After getting into higher end HiFi and winding up with a main system that includes Dynaudio Confidence C4 speakers, it’s hard to enjoy transducers with major sins of commission. Even my Beloved Bozaks have sat silent since the evening the C4s came home. But, I always wondered-would the rarest of the rare, the original patriarch, the Speaker That Started It All…would it, could it be something I’d enjoy? Someday, I hoped I’d be able to answer that question.

Back to the Plot

So, we know that somehow, through some mechanism, a Lansing Iconic system housed in a Model 810 Home Loudspeaker Console managed to find its way to Technisonic Studios in St. Louis, Missouri. Technisonic studios was founded in 1929 by Charles E. “Bud” Harrison, initially due to his interest in working with the deaf. The recording space was originally located in the Central Institute for the Deaf, where this speaker makes its first (and thus far only) appearance in the photographic record, as a studio playout speaker. After blowing out the exposure on this photo, the characteristic grill shape is unmistakable.

Above Photos Courtesy Bill Schulenburg

Above Photos Courtesy Bill Schulenburg

Top photo: Bud Harrison

Middle two: Central Institute For the Deaf

Bottom: Technisonic Studios

After a decade or so on Jefferson Ave, Technisonic studios then moved to a facility on Brentwood Blvd, where it remained until the late 80s. It was then moved to a location in St. Louis City to make way for a shopping complex. Technisonic was the oldest and largest production facility in the region, housing everything in one place for audio and film production, later with newfangled electronic video added. I do mean everything-recording, cutting, plating, pressing, shooting, post-production, printing, and tape duplication was all done in house. It was considered the best studio in the city, and kept up with the times, moving from disc to tape, mono to stereo, stereo to quad, and up to 16 then 24 track recording with quadraphonic monitoring, and even had the world’s first console with Automix custom built by Automated Processes installed in 1975! Some of the highlights of the studio’s work include episodes of The Lone Ranger and The Green Hornet for network broadcast, many Anheuser-Busch commercials (a 45 I’ve had since childhood of The Busch Bavarian Beer Song is on the Technisonic label), the first Ike and Tina Turner recordings, Bob Kuban and the In-Men’s “The Cheater”, Chuck Berry’s Mercury recordings, Manfred Mann’s Earth Band’s Spirit In The Night was tracked there, the classic disco group Breakaway’s two albums were recorded there, as was Jasmine (the Carol Schmidt/Michelle Isam project), parts of Bobby McFerrin’s “Medicine Man”, and an Albert Brooks comedy album along with an appearance by Stevie Nicks in the early MTV era. The studio also recorded and produced thousands of radio shows, local groups, film soundtracks, and commercials. Technisonic was The Place To Go if you wanted to make a studio recording in town for decades but closed in 2010. A fascinating book could be written about the history of this studio.

Focusing back on this speaker, George told me that it was in use until the late 1980s, and when he left the studio after 30 years, in 1992 (when the author was born!), he took the speaker with him, as it wasn’t wanted by anyone there at the time.

At least once a month for the past year, I had gone on a dive down the rabbit hole of the internet, looking, hoping, searching for some sign that this speaker existed anywhere else on the planet. I had been hesitant to post anything publicly on the web, as anyone with enough google-fu might be able figure out who had the speaker in their possession, and add it to their private collections. Audio collectors can be a rabid bunch, particularly when something heretofore undocumented and historically significant comes up, and I never had the pocketbook to compete with a real offer from well-funded collectors. But my quiet queries had led to nothing. It appeared this was The One and Only. I still haven’t SEEN another, but read on…

Thursday, March 10, 2023, 370 days later

I’m walking out my door, lunchbox in hand. My phone rings, and I see it’s George. I froze.

There would only be one thing he could be calling about, and I didn’t have the time to sit down and have a proper conversation about all I had found. So, I let it go to voicemail, got in my car, connected my bluetooth headset, started the call back, and began my commute to work. Thankfully, he answered the phone, and he explained that his facility was being restructured, and the office the speaker lived in needed to be cleaned out. I started to explain some of the research I had done, and tried to share some of the information I’d learned and alternate ideas about the timeline, in an effort to show I both cared about the history and establishment of a viable chronology. But I guess my intention didn’t make it through the excitement, and he seemed offended that I’d dare question Mr. Harrison’s word. I bit my tongue, and decided to shut up, so as not to destroy my chances of owning a real Lansing Iconic! So, he said that it was time for the speaker to find a new home, and we decided on a date for four days hence, at 9:30am. My shift at the TV station started at 11, so whatever happened-it would be a memorable hour! I also needed some time to clean out the van, and I wanted to choose a day without any rain in the forecast. He agreed. There was no mention of any monetary transaction. I’d saved the address I went to before, so I didn’t even need to ask for that-I made sure I was ready, should the possibility to acquire history arise again.

Well, as you might imagine, the next three days were spent going back over all of my research, reaching back out to collector friends who had been consulted the year before, and generally being an excited mess, telling the story to anyone who would listen. Reactions ranged from “fire it up!” to “dear god, whatever you do, don’t even dust it off!”. The break point was about age 50, as most of my friends closer to my own age were excited at the prospect of such a speaker making music again. The more seasoned veterans encouraged the most caution possible, to the point of encouraging me to call several museums straight away. I had mixed feelings, seeing both sides of the picture. My interest lies in actually hearing what the past sounded like, to the best of our ability, and trying to enjoy classic designs for the strengths they have. It’s a goal to someday have a series of operational displays chronicling the evolution of audio reproduction from its nascent cylinder recordings up to a modern window into the sonic landscape.

I realized that the only repairs the Iconic might need, provided it really was working as late as 1988 or 1990, would be a power cord replacement and replacing whatever the filter capacitor was in the power supply. While some people cherish the idea of using 40-80 year old capacitors in their designs for the sake of originality, I am of the opinion that modern, high quality components (especially when replacing electrolytics and selenium rectifiers) are going to provide an excellent upgrade in performance over whatever was available before. Components drift over time, can become dangerous, and we don’t often have data on why the original designers of classic gear chose what they chose, but those components today are sure to have drifted from whatever original sonic characteristics they may have exhibited when new. But that’s an argument for another day.

Of course, I know better than to haphazardly replace components unnecessarily in a supposed prototype and heretofore undocumented variant of a Lansing Iconic, I was certain I had to ensure the safety of the irreplaceable field and voice coils. Going back over the photos I had with a microscope to try and discern any differences from documented production versions of each assembly, I noticed that the DC field supply didn’t have a visible can capacitor on the top, as did the production version supplies, and supplies made after the sale to Altec. Perhaps someone had been in there to replace it? I hoped so, so I wouldn’t feel as bad about replacing whatever filters were in there. I also thought that perhaps Lansing had used some of the excellent but highly costly film capacitors, which do have a service life of many decades. Prudence dictated testing the crossover network with a sacrificial test speaker before applying any signal to the voice coils. A new crossover could be built, if the original was found severely faulty. Original 1930s Lansing voice coils could not be replaced. The thought also crossed my mind that the speaker could have had any number of replacement parts installed throughout its 50 year service life. Studios of this caliber maintain their equipment, after all. The four days ticked by slowly, and Monday afternoon, I texted George for a confirmation that we were still on for the next day. A yellow thumbs up was the reply. It was on.

Tuesday Morning, March 14, 2023. The Day

Sleep was fleeting, the night before. Normally a sound sleeper, every half hour, I woke up, looked at my phone, wondering if it was time to go. I’d caught perhaps a couple total hours of sleep by the time I had to go through the morning routine. My wallet had as much cash as I could scrounge on short notice, but I had a feeling I might not need it. I loaded up the moving dolly, some moving blankets, and made the drive I’d made just over a year before. This time, I wouldn’t leave without my prize.

Pulling up, I saw George outside talking to some people, and I waved at him. He recognized me, and we walked inside. The speaker was still right where it had been sitting, with the microphone and radio remote amplifier sitting on top. I decided to be bold, and ask if I would be able to take the other two pieces home today, too. His response: “we’ll talk about that”. Cool. This could get interesting. This was my chance-I began to lay out the information I’d found, and said that while the last thing I wanted to do was poke large holes in the story his former boss told, I explained my theory about the Acoustical Society presentations. I then detailed the information I’d found about the first Audio Engineering Society Audio Fair, and the timeline of the original Lansing Manufacturing Company, and showed him the catalog scans. He accepted that ASA could have turned into AES, and seemed surprised I’d found the original promotional material detailing the speaker. My intentions had made it through in person-I really wanted to try and prove the origin story. We then went on a tour of the second building in the complex, where there resided two of 22 built Nimbus Records DVD mastering laser recorders that looked straight out of Star Trek, and the packaging production lines that were being moved to another state for consolidation.

I also got to talk to some of the other employees, one of whom interestingly relayed that they’d duplicated a bunch of Zip Discs for a certain supplier that year. It’s fascinating to see how long technologies can stay around in industry.

We found some suitable boxes and packing material for the microphone and preamp, and I took some photos so my coworker and I could study them over lunch. I wheeled the dolly in, folded the tongue extension down, and got the speaker loaded. On first inspection, everything looked solid, and tilting it back revealed that nothing moved. I carefully navigated it though some doorways, and it was finally out in the light of day. I hadn’t asked about any form of payment, and was frankly a bit worried that I hadn’t brought enough money, and had already gotten the speaker out of the building. Once we got it into the parking lot, George said “If you sell it, I get half”. He relayed that he’d been offered a significant amount of money for it in the 1970s, but declined then, and believed now that it should be in a museum. I was stunned, but immediately agreed, and we both understood that I wanted to keep the speaker and try to document its history as far as possible. While it is an early Lansing field coil, which makes it a lifetime achievement for any audio collector, I feel that the five decades it lived in the St. Louis music scene was even more historically interesting, and I will do whatever it take to honor that heritage.

Tilting it back up and off the dolly, I felt something shift ever so slightly in the top of it, andsquatted down to see exactly what I was dealing with. Turns out, the board holding the crossover, power supply, and horn assembly was removable, and connected to the bass chamber with a plug. Excellent! I photographed the sides and back of the cabinet, took the board out, and did the old tilt’n’push up the well-padded bumper and into the back of my van. Tucking moving blankets around the cabinet and tweeter board ensured it shouldn’t moveduring the drive to its new home.

Before I left, I texted the photos to several people, including one deep-pocketed exporter to Asia of all things historical audio. A large haul of interesting postwar gear haul I’d gotten inDecember didn’t even raise his eyebrow, and he told me he only cared about Pre-WWII equipment at this juncture. Figures, as when I’d met him in 2018, he was buying a 1928 RCA Sound System Rack full of gear that was about 7 feet tall from another collector friend.

The exporter called me within a minute of sending the photos, and all I could do was chuckle at the speed of his response. He was, as expected, quite shocked, and claimed that there were two or three more he knew about, and wanted to buy the speaker immediately. I was surprised, but not shocked. to hear of the existence of others. If anyone in the English speaking world knew of another, it would be him, and I kind of expected others to have been built. Otherwise, the catalog illustration would not have been included in a publication. Of course, I said no to his purchase offer. I really wanted to get information about this Iconic, and what I could expect. He seemed surprised that I would want to actually LISTEN to the beast, and was concerned that any modifications I would make would destroy originality. The exporter encouraged me to just run it as-is, and that “it probably work” [sic]. I told him that I’d evaluate what was there, but I had to replace, at a minimum, the power cord and the field supply capacitor(s). But, I would leave the old caps in a bag if the next owner for some reason HAD to put it back. This seemed to placate him, and he continued to pester me for a price. I declined to provide any guidance, and he finally threw a number out, which I honestly thought was on the lowest end of what it might be worth, even before documenting and testing. Declining again, by this time, I’d reached the parking garage and had to go to work. I wished him well, and said I’d be in touch with more information as it developed. That day at work went by in a blur of excitement and frantic message-sending between tasks. One friend I reached out to said he’d seen one like mine, only once, in the 1970s. So, the count is up to five. Maybe.

Getting home in the evening, I pulled the cabinet out of the van, got it onto my front porch, and snapped this photo as I admired its beauty. I had been so excited to finally land my prize that I’d never really considered the visual design excellence of the cabinet! I was rapidly falling in love with my new find.

Bringing the assemblage inside, I decided that the first order of business was to see what was under the power supply. Removing it from the board, I saw a beautiful old Aerovox dual 20uf can capacitor in a clip, with both its’ sections in parallel. It looked original, but I saw I could easily and non-destructively add a new capacitor alongside the old. The power cord looked to have been replaced in the fifties or sixties, so I didn’t feel bad about my plan to replace it again. The fuse was good. Next up was to see what diaphragm was in the compression driver. I had fears of a modern replacement being installed at some point throughout its life, and a friend had helpfully provided a visual history of diaphragms that fit that driver. With shaking hands, I backed the screws out of the cap and….lo and behold, a real, authentic, spun aluminum Lansing diaphragm! My hopes shot up that this could be a truly unmodified original. Metering the diaphragm, it read a perfect 7.5ohms DCR (DC resistance of a speaker is typically half the AC impedance), as this is a 15ohm nominal driver. Next up was the tweeter field coil, which measured at 635ohms DCR, against a stated 650. Close enough.

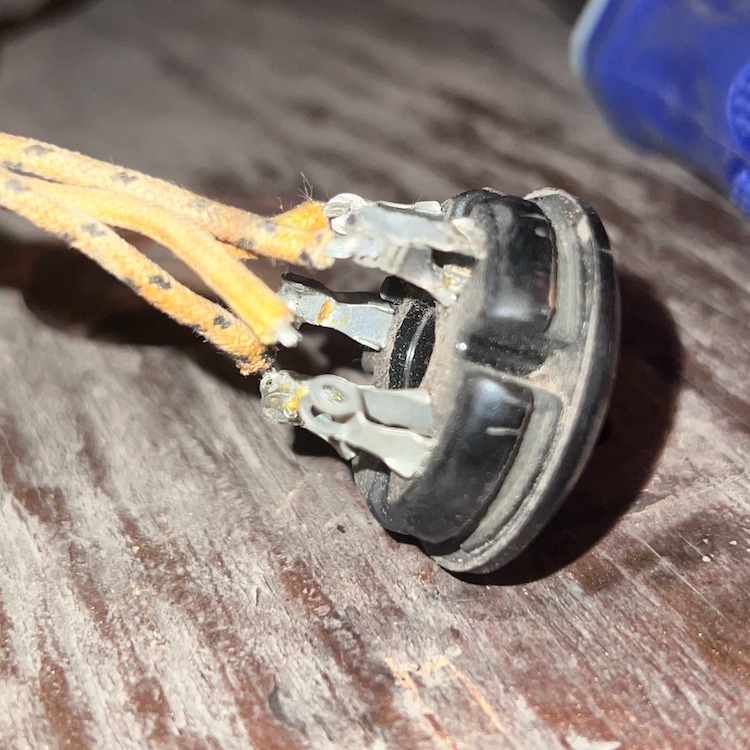

Then, the woofer. I poked around on the 6 pin connector for a bit, hoping to find both windings before taking the back off, but was only able to find the voice coil. My stomach dropped, as Lansing Manufacturing woofers are nigh-impossible to get. The connector is a 6 pin affair, with two large pins and four small pins. I would assume that any two similar pins would be the field coil or voice coil, respectively. So, with trepidation, I removed the back of the speaker and was greeted with….

An absolutely gorgeous Lansing 815S woofer! Looking at the connector, the field coil was between one large and one small pin, diagonal from each other. The least likely connection I could think of! Oh well, Perhaps this really was a prototype. Checking the coils at the speaker terminals, the voice coil read 2.9ohms DCR against a 6ohm nominal impedance, and the field coil was 1506ohms, against a 1600ohm figure defined by a forum post on Audio Asylum by Lansing Guru Steve Schell. The cone looked great from the back, and it moved when I ever so gently pushed near the center of the cone. Satisfied, I buttoned it back up and called it a night. That was a lot of adventure for one day!

Wednesday, March 15, 2023

The next evening, I decided it was time to check the power supply and crossover. My one local friend that actually played with field coil drivers (Ron) asked to be on the phone with me, as while I understand basic electronic troubleshooting, he has an idea of what may or may not be right, having used and built field coil supplies. He was gun-shy, too, about replacing the capacitor, but suggested I zip tie the new cap right to the old one so as not to damage the label with tape or by drilling a new hole. I replaced the power cord, pulled the rectifier tube, brought the transformer up on a variac, and got the right voltage on each side of the transformer. It buzzed a bit but didn’t give out. So far, so good. Next, I carefully desoldered the wires from the existing capacitor and attached them to the leads of the nice, new Nichicon 47uF electrolytic and shrunk down some heatshrink to insulate the connections. Structural zip-tieing ensued, but this is a repair that’s invisible from above, and ensures that any Absolute Originalist can undo my work. I even took care not to bend the ends of the wires as best I could from being wrapped around the tab of the old capacitor. As non-destructive as possible.

.jpg)

With the power supply ready for testing, Ron advised to only run it up to about 60v on the variac, as without a load, the voltage on the simple unregulated choke-cap power supply could shoot much higher than intended. All seemed well, and the supply made around 180v or so unloaded at 60vac. The transformer buzzed a little bit, but, after nearly 90 years, it’s seen a lot. Next up, was the crossover network. Unscrewing the positive wires from the low and high output of the crossover, I clip leaded in a test speaker. I brought my selected amplifier over, connected my phone as a source, and listened to each section of the crossover. The lows didn’t have highs and the highs didn’t have lows! The crossover sounded like it was operational enough to try. By this time, it was well past midnight, and I was bushed. But, two fellow late night denizens of the internet urged me to give the speaker a full test before I called it an evening.

The crossover was reconnected to the harness, my tools were set aside, and I slid the board back into the speaker. Carefully aligning the woofer cabinet connector. I reconnected the wiring harness, set a variac and amplifier on top of the speaker (with protection underneath), set my phone to “mono output”, and reconnected one side of the Apple iPhone headphone adapter to the amplifier input.

Now, a word about this amplifier. It’s a custom push-pull 6V6 amplifier built by a longtime audio friend back in 2015, part of a pair of tube amplifiers I asked him to build which had extraordinary low frequency response. I had purchased a pair of the ElectroVoice 30 inch woofers, and wanted to drive them with tubes, but few affordable tube amplifiers go down into the infrasonic range. At the time, I had planned on moving into a building a friend owned, and the speakers were stored there already. He came up with this pair of amps built on Grommes chassis but using Radio Craftsmen RC2 output transformers, and said they delivered at least a few watts down at 15hz, and about 10 watts throughout the rest of the frequency range. Perfect. I listened to them full-range, and was absolutely floored. Despite their small power, they sounded substantial, controlled, and positively modern. While not the quietest amplifiers in nearfield listening, I elected to use them as my main amplifiers driving ElectroVoice Sentry Vs in my mother’s apartment, which is where I was residing at the time. They never have driven my big 30” woofers, but have become my go-to test amplifiers for vintage speakers where I absolutely cannot have any turn-on thump or possibility of DC going to the voice coils. Also, all these classic speakers were designed with tube amplification, so it feels right to continue that lineage.

It was time. I selected Frank Sinatra’s classic Come Fly With Me, pressed play on my phone (using Tidal HiFi, of course), and turned up the variac to 50v. Standing behind the speaker, I saw the rectifier light up, heard the power transformer buzz, and flipped on the amplifier. After a few seconds, some very muffled sounds came out, and I started giving the speaker more voltage. Quickly, it became apparent that a) the compression driver performance varied wildly with field coil voltage, and b) the woofer wasn’t working. Shutting the rig down, I started troubleshooting. I had verified the woofer coils, connections, and crossover output. But, I hadn’t verified the wiring harness. As I had response from the tweeter, I knew that both the field coils were working, as they’re in series and an open connection would result in no sound at all. Now that I knew the pinout of the woofer cabinet connector, I metered the connections back to the crossover, and lo and behold….one pin was open! Cracking open the connector, I saw that one wire had broken loose from a pin that fed the voice coil. A minute later, the soldering iron was warmed up again and it had been reconnected. I performed the same test. This time, I heard a woofer! Dialing up the voltage through 70, 80, 90v revealed something that one rarely hears in audio-the performance of a driver with the magnetic gap properties changing rapidly! The overall change to the sound was like dialing out the low and high pass filters on a channel strip-the frequency response extended by octaves on either side, until I finally stopped, just over 100 volts. Online advice recommended avoiding driving the supply at lowe than modern line voltages to avoid stress on the octogenarian coils.

I walked around front, sat down, and began listening. The music just….flowed. Frank’s voice had warmth, presence, the band was integrated…this was a speaker that did NOT shout at me, nor did it beat me over the head with horn resonances, Mr. Stephens had done a masterful job with this sectoral horn design, Lansing had machined a superb driver, and Blackburn had established the parameters needed to make an acceptable loudspeaker. All other multicell horns I’ve heard have quite noticeable lobing from cell to cell-this had far less of that than I thought possible. It sounded like a 1937 HiFi speaker, but in an enjoyable way. Compared to most of the factory Altecs and JBLs involving compression drivers that I’ve heard, and most JBLs involving conventional direct radiators, this speaker was mellow, warm, inviting… It is a thinking person’s speaker, not a “melt your face off” rock’n’roll ready monstrosity. I think I sat through a solid half of the classic Ella and Louis album before my tiredness caught up with me, and I powered down for the night. It was by then, almost 3am.

Friday, March 17, 2023

Having reveled in the win for the next day, I revisited the speaker once I got home from work for another, more critical audition. Firing up my usual demo tracks, I began to notice the concerning lack of extreme HF-for a speaker that was initially rated out to 10khz and then out to 15khz with minimal visible changes, I sure wasn’t getting much up there. And, I began to notice the somewhat jagged midrange integration with the woofer when playing acoustic guitar tracks I knew well-Michael Hedges’ Aerial Boundaries wasn’t nearly as cohesive as it was on other systems, even old ones. Most concerning, though, was when the bass guitar came in. I had been listening to the speaker at below conversation level on my initial test, this time was leaning into it a bit-not nearly what one would call “loud”, but perhaps the 75db-ish area. I heard that characteristic rattle of a sick loudspeaker on bass notes. My heart sank. I immediately switched tracks to something less strenuous on the low end, and got my ear right up to the woofer. No rattle. Pressing, tapping, and knocking on various parts of the cabinet revealed no loose sympathetically resonating trim pieces or panels, either. I decided to cue up the classic cover of “Walking On The Moon” by the Yuri Honing Trio, which is superbly recorded and has an acoustic bass that digs deep. Well, the woofer rattled at that most moderate level. Dang it. More investigation would be required. Reluctantly, I powered it off again. This was turning into a real project-crossover cloning, and some sort of woofer surgery.

Sunday, March 19, 2023

I’d spent Saturday looking around the internet to see if anyone had crossover schematics, or even hypothesized as to what could be in the sealed metal can. No luck. This day also contained an hour-long call to Frank, the local speaker rebuild guru. He has performed many miracles, and set thousands of drivers right, with clientele spanning the globe. Frank was aghast that I had found an Iconic, much less an obscure home version. While discussing the find, I mentioned that the audio rumor mill never mentioned the existence of another in this town, and that jogged his memory. He said “that guy who worked on The Simpsons” had told him about an old Lansing speaker years before when Frank had done work for him, and he really regretted not inquiring further. I started laughing, and had to tell Frank that the speaker he’d heard about was now sitting not ten feet from me at this very moment! I relayed that “the Simpsons Guy” was my friend Stuart! Frank was, to say the least, shocked. But, that reinforced my thought that there can’t be too many more Iconics floating around my city! He has been in this field for over four decades and has seen almost everything. If he only knew of one, I trusted that any others would have disappeared decades ago.

After that, I brought up the difficult topic: The Woofer Rattle. Frank was sad to hear the woofer had issues and said he’d have done the same thing: measure the coils and just try it. While I had been completely non-invasive on the first opening, I would have to dig deeper this time. I hypothesized that, if lucky, rotating the woofer 90 or 180 degrees could help cure it. Frank opined that there was perhaps a 20% chance of success, but it was good practice after 85 years anyway. He also suggested attempting to see if anything was loose in the magnet structure, or perhaps the speaker itself was not bolted in tightly. Something could even have been stuck between the cone and cabinet. All good ideas. But, he would be unable to look at the driver for some time as he was recovering from a pair of surgeries and couldn’t lift more than 4lbs. I was relieved to hear he was recovering, but my hopes of a quick jaunt over to his place for a look-see would have to wait.

After the call, I laid the cabinet down on its front (carefully!) and removed the back for the second time. Removing the back, I found that the speaker was tightly bolted to the front baffle, the magnet didn’t shift, and when I pressed on the cone harder than the first gentle nudge, I felt and heard The Bad Noises. Ugh!

Out came the socket set, and I backed the four bolts out holding the driver in, and lifted the woofer free of its baffle, perhaps for the first time since 1938! Flipping it over, I was delighted to see that the cone was in perfect condition, looking factory fresh after nearly 9 decades of service. I observed a little bit of dust on the bottom area of the cone, which I brushed off with a gentle paintbrush, and vacuumed out the small pile of dirt remaining on the baffle where the bottom of the speaker had been. Clearly, there had been some buildup over the years. Then, it was time to learn the truth: I’ve “push tested” many speakers over the years, both working and problematic, and this one was certainly the latter. I could feel and hear resistance, which did not clear by pushing on any area of the cone/coil interface, or applying centered pressure. Gah! A museum-quality woofer with a major malfunction. I knew it wouldn’t make any sound again until this issue was solved-whatever it takes. Eyeballing the suspension around the coil more closely, the spider looks an awful lot like my 1936 12” Jensen Field Coil in my EH Scott Allwave 15. Fascinating! Placing the woofer back on the baffle and rotating it 90 degrees, I snugged the bolts back down, put the back on, and stood it back up. My, my, what a pretty box! Sending the woofer images to Ron The Field Coil Guy, he thinks that perhaps the suspension can be adjusted, but only time will tell what is possible. I have dreams of being able to unbolt the whole magnet structure, lift off the basket and cone in one piece so any debris in the gap can be effectively cleaned out, and the voice coil inspected for damage. Another friend suggested compressed air, which might also work, but that seems a bit dangerous. To quote an obscure line from one of my favorite films, The Hunt for Red October, “the data doesn’t support any conclusions at this time”.

While the tweeter board was out again, I took the opportunity to unbolt the crossover, and look underneath. It’s a strange feeling to know that likely the last person to fiddle with these pieces was likely an employee of Lansing Manufacturing Company-perhaps even Lansing or Blackburn themselves! Alas, the bottom of the crossover is as neat and tidy as it is unhelpful in discerning what might be inside the black box. Several forum posts will ensue to see if anyone has depotted, or has documentation of, the contents of this container. No matter what crossover I end up using for the long term, I feel driven to recreate what was originally there to gain as accurate a glimpse into the sound of the past as I can.

This speaker has turned out to be far more interesting, and a larger project than I thought. But it seems restorable. The big question is: how original can it be kept? I don’t much like shelf queens, but a Lansing Iconic must be evaluated as a whole. These parts are only original once, and my goal is to restore the entire unit to full working order using the least invasive techniques possible. You don’t always want to meet your heroes, but sometimes it is nice to meet your Icons.

This story will be continued in Part 2.

Brief bio:

David MacRunnel

David MacRunnel

David MacRunnel is a lifelong audiophile, with a love of music, records, and antique audio starting at age three. As he entered his teenage years, he started rapidly climbing the upgrade ladder, while teaching himself to record music, provide live mixing services, and audio/video digitization. This eventually led to a position on the recording team for the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, as well as a number of schools and venues. With the COVID-19 Pandemic taking its toll on the audio industry, he moved into a stable full time position in television broadcast engineering. Audio fidelity has always been his goal, and with exposure to modern digital recording and reproduction, he has become less of a strict vinyl evangelist than in his teenage years. But, he still enjoys his approx 10,000 records, continues to add LPs to his collection, is passionate about music, and the differences in devices that reproduce it.

How I Met Michael Fremer:

I had been reading That Other Magazine since around age 12 (my local library didn’t have any other audio mags!). I finally got the courage to email Michael with a long and rambling series of questions around age 14, as I enjoyed his writing and what he had to say. To my surprise, he took the time to respond and offer sage advice. Over time, he started asking me questions that led to my own audiophile odyssey. Things such as stacking multiple sets of speakers, extending phono level RCA cables, and having speaker switchers in the signal path were harmful to the effective reproduction of sound. Basic stuff, I know, but for a 14 year old, it started me down a rabbit hole of upgrades and sonic discovery. I credit him for nudging me towards the higher end of audio and developing the thought processes that lead to critical listening skills.