John Lennon Once Put A Shitty Pressing Of His Music on Trial-- And Won!

Years before the Mofi scandal, Jay Bergen's "Lennon, the Mobster, & the Lawyer" tells how the former Beatle used the good ol' shoot-out to show a federal judge how a shitty pressing hurt his reputation as an artist.

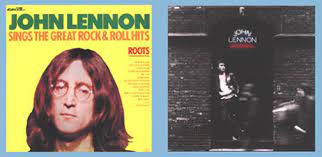

The year was 1976, long before "hot stampers" were even a thing. John Lennon presided over a good old-fashioned record pressing shoot-out-- in federal court, no less. The pressings played in the Southern District of New York's federal courthouse had songs familiar to lovers of Lennon's ROCK 'N' ROLL album, his beautiful homage to early rock and roll, but the two albums' quality couldn't have been farther apart. The first contender in the shoot-out, naturally, was Lennon's official release, the all-caps ROCK 'N' ROLL, a criminally under-heard masterpiece. The second record, Roots, came to be after Lennon gave a 7 1/2 ips duped copy of the ROCK 'N' ROLL tracks to music-industry scoundrel Morris Levy, one of Lennon's worst decisions since hiring Allen Klein. Levy took the inferior tapes and packaged the music in maybe the lousiest sleeve of all time, a lame yellow-and-green number (hobbit colors!) with a crude cut-and-paste photo of a Dirty Mac-era Lennon sporting a sour expression (I hate this record!), and released it without Lennon's permission as a mail-order-only album, Roots: John Lennon Sings the Great Rock & Roll Hits. It was, in the words of Neil Young & Crazy Horse, a PIECE OF CRAP!

How did the crooked Morris Levy manage to get reels of tape from John Lennon? Jay Bergen's superlative legal memoir, Lennon, the Mobster, & the Lawyer, published as part of Devault Graves' Great Music Book Series, begins with John Lennon receiving a summons and complaint from Morris Levy, stating he was being sued for copyright infringement for lifting maybe a phrase, maybe half a line from an old Chuck Berry song. Levy and Big Seven Music owned the copyright to the Chuck Berry fast-car song “You Can’t Catch Me,” which contains the lyrics, “Here come a flat-top/He was moving up with me,”[1] a line which Lennon later admitted inspired the opening line of the Beatles’ song “Come Together.” Bergen's account of John Lennon’s legal battle against the classic sleaze Morris Levy is immensely entertaining, as this author and trial lawyer's elephantine memory and carefully-documented legal files reach back nearly fifty years to give the reader several gold nuggets of musical and legal history:

· The overheard phone conversation which inspired the funniest line from the Stones’ album Some Girls, "What's the matter man, we're gonna come around at twelve with some Puerto Rican girls just dyin' to meet you!";

· John Lennon’s testimony (under oath) explaining the album-making process, from concept and song selection to recording, mixing, mastering, and selection of album art;

· Federal Judge Thomas Griesa entering the case with a great love of classical music but almost no knowledge of rock, until John Lennon’s charismatic testimony convinces the somewhat staid federal judge as to the artistic merits of rock music.

Interestingly, the trial did not turn on whether “Come Together” infringed upon Chuck Berry’s “You Can’t Catch Me”[2]—either because Lennon was wary of the endless litigation George Harrison endured in the “My Sweet Lord”/“He’s So Fine” case, or simply because of his unwavering honesty, the former Beatle decided to settle with Morris Levy, agreeing to record three songs Levy owned on the next John Lennon solo album, a Phil Spector-produced collection of rock ‘n roll cover songs. Neither Lennon nor Levy got what they wanted: after a classic Phil Spector melt-down, in which the maniac producer fired a round into the ceiling of the majestic A & M recording studios in Los Angeles and absconded with the master tapes, Lennon was forced to put his ‘50s covers album on hold and release “Walls & Bridges” instead.

When not “ROCK ‘N’ ROLL” but “Walls & Bridges,” sans the promised three songs, became the “next” John Lennon record, Levy began hinting that he was going to bring Lennon to court. Worried that he might face even more litigation, Lennon soon began capitulating to more and more of Levy’s increasingly ridiculous demands— John even consented to taking the Plastic Ono Band to Levy’s upstate New York farm to play old rock songs in the guy’s back yard. Although a home visit/backyard concert featuring John Lennonwould give most people I can die now satisfaction, for Morris Levy it wasn’t enough—he got Lennon to agree to go on vacation with him and his family to the worst place on Earth—Disney World! (Lennon spent most of the time in his hotel room with his lawyers, going over documents relating to the dissolution of the Beatles’ partnership.)

The culmination of Levy’s incessant pestering was John’s disastrous decision to hand over to Levy a duped copy of a preliminary version of the “ROCK ‘N’ ROLL” album. Without Lennon’s permission, Levy took the inferior 7 ½ ips reel-to-reel tapes[4] and put out a schlocky cash-in record called “Roots: John Lennon Sings the Great Rock & Roll Hits,” a record whose bootleg-quality sound was matched by its bootleg-quality cover, a grainy, obviously cut-out photograph of John Lennon circa 1968. As bad as the cover image was, Lennon was even more appalled by the back of the album, where Levy had placed prominent ads for the lousy “Soul Train Super Tracks” and “20 Solid Gold Hits,” which included Carl Douglas’s depths-plumbing “Kung-Fu Fighting.” Other mistakes revealed the low-rent nature of Levy’s record. After every song title, Lennon is credited as the songwriter, despite the fact that as an album of covers, it had no compositions by John Lennon, making it appear that the singer was trying to take credit for writing such classics as “Peggy Sue”[5] and “Be-Bop-A-Lula.”[6] In contrast to Sgt. Pepper’s artful psychedelic inner sleeve, Levy used that space to shill bargain-counter compilations like “40 + 1 Original Country Goldies,” “Rock Is Here to Stay,” and “The Now Explosion!”. Even worse, Levy planned to sell the record exclusively via mail order with el cheapo television spots which featured a montage of old photographs of John Lennon playing with the Beatles, something which enraged the iconic songwriter.

As egregious as this blatant act of piracy was, Levy took a page from the Trump playbook and double-downed, falsely asserting that John Lennon had agreed to all this! Part of the pleasure of Bergen’s book is witnessing how little traction such big lies gain in federal court, especially when dealt with by a lawyer as skillful as Jay Bergen and a judge as thoughtful as Thomas Griesa. Reading about Levy’s hapless lawyer William Schurtman swinging and missing repeatedly in federal court reminds one how satisfying justice can be.

Although understandably wary of lawsuits, Lennon became convinced that Levy’s cut-rate “Roots” album and ads harmed his image as a serious artist. With Bergen’s help Lennon counter-sued Morris Levy under Section 51 of New York’s Civil Rights Law, which provides what is known as a “right to publicity,” that is, the right to protect one’s name, image, or persona from being commercially exploited without permission.[7] Our greatest legal scholar, Judge Learned Hand, explained the harm done to an individual whose right to publicity has been violated:

His mark is his authentic seal; by it he vouches for the goods which bear it; it carries his name for good or ill. If another uses it, he borrows the owner’s reputation, whose quality no longer lies within his own control. This is an injury, even though the borrower does not tarnish it, or divert any sales by its use; for a reputation, like a face, is the symbol of its possessor and creator, and another can use it only as a mask, and so it has come to be recognized that unless the borrower’s use is so foreign to the owner’s as to insure against any identification of the two, it is unlawful.[8]

Judge Learned Hand’s commentary certainly puts into perspective the legal significance of Levy’s selfish, ugly decision to plaster John Lennon’s face on each copy of the sorry “Roots” album. In determining whether Levy had infringed upon John Lennon’s right to publicity, Judge Griesa compared the quality in both sound and image of Lennon’s solo albums to the flimsy crud Levy had shilled (without permission) on local New York television. As mentioned above, Judge Griesa conducted in his federal court-room an actual “shoot-out,” comparing the lackluster sound quality of Levy’s “Roots” album, manufactured using inferior tapes with rough mixes of the songs, on recycled vinyl, with the sound quality of Lennon’s “ROCK ‘N’ ROLL,” which had most of the same songs but were manufactured from the master tapes and with virgin vinyl. When the case was later reviewed by a Court of Appeals judge, that court found that the cover for “Roots” was “cheap-looking if not ugly” while noting that the sound quality was “shoddy and fuzzy… with one out-of-tune track.”[9]

In addition to the right-to-publicity claim under New York law, Bergen also sued Morris Levy in Lennon’s behalf under the federal Lanham Act, which imposes civil liability upon individuals who engage in deceptive trade practices. More specifically, Lennon’s counter-suit alleged that Levy’s fifth-rate television spots and abaxial bootlegs were likely to cause dilution of Lennon’s brand through “blurring” and “tarnishment.” The Lanham Act describes “blurring” as the damage done to a distinctive mark by counterfeit goods, as the similarity between the bogus and authentic product blurs the distinction between the two—think of the “McDowell’s” restaurant in the Eddie Murphy film Coming to America. “Tarnishment” occurs when a similar but inferior product damages a mark’s hard-earned reputation for quality, for example, in the ‘70s and early ‘80s, the sale of polyester golf shirts in discount stores, complete with a variety of teensy creatures on the chest, resulted in La Chemise Lacoste abandoning the U.S. market-place for a number of years.[10] In this case, Judge Griesa not only considered the “Roots” album’s schlocky cover and sound quality, but also Levy’s use of recycled vinyl for the “Roots” album while the “ROCK ‘N’ ROLL” album was pressed on premium virgin vinyl. There’s probably no greater vindication for one’s vinyl obsession than reading trial transcript excerpts about a particular pressing’s deep black glossiness, the “presence” (or lack thereof) of Lennon’s voice, the surface noise (or lack thereof) of a particular pressing, and the (losing) argument that a particular record sounded better in court because Lennon used the Record Plant’s professional turntable for optimal playback.[11]

John Lennon’s “ROCK ‘N’ ROLL” is an important record, not just because it was produced by such legendary figures as Lennon and Phil Spector, Engineer Jimmy Iovine, and Mastering Engineer Greg Calbi, but also because this record established definitively, in the serious setting of federal court, that rock music was not disposable music for kids, but a legitimate American art-form to be taken seriously. “ROCK ‘N’ ROLL” has been unfairly overlooked, and hopefully Lennon, the Mobster & the Lawyer will help change that, but until that happens a good copy of the record can be had for about twenty dollars. At the same time, a copy of the bootleg record is advertised on Discogs for $399.99, quite a price for a piece of junk.[12] Matching the quality of the bootleg’s cheap vinyl was the similarly bad lawyering for Morris Levy. A great moment occurs when the outmatched defense attorney, William Schurtman, insists that the court listen to the sound quality of a pair of tracks (one from the original, the other from the bootleg) in open court before Lennon’s expert witness (rock critic Dave Marsh) could have an opportunity to comment. (Commenting on the sound quality of the “Roots” album in general, Marsh testified that “It is shoddy, it is fuzzy. It sounds like those old bootleg records that kids used to make out of cassettes.”) After the two versions of the Fats Domino standard “Ain’t That A Shame” were played for the court, Schurtman jumped up with an objection to Marsh’s further testimony, arguing to the Court, “you don’t need anyone to tell you what you just heard.” Judge Griesa replied to the objection with a devastating comment from the bench:

"Do you want me to tell you [what I heard]? I don’t think there is any comparison. The ROCK ‘N’ ROLL [album] is so much clearer; the voice was very poor and indistinct on Roots, it was almost hidden there. I could not tell it was John Lennon singing or anybody singing: it was [just] a voice…. Now, the ROCK ‘N’ ROLL [album], the voice was clear and distinct, and every other element was distinct, and the beat was distinct…."

In Lennon, the Mobster & the Lawyer, Trial Lawyer and Author Jay Bergen transports the reader inside the mind of John Lennon more effectively than some of the numerous books by music journalists or Beatles historians. Of course, as Lennon’s lawyer and friend, Bergen probably spent more time with John Lennon than many Beatles experts, and he used that experience to craft a portrait which revealed not only Lennon’s intense commitment to rock music as an art form, but also his astonishing courage and generosity-- this is a man who died partly because of his policy of rarely refusing to sign an autograph. But what makes this book essential is the electric dynamic created when Bergen reveals that Judge Griesa is both a discerning listener of classical music and a complete novice when it comes to rock and roll music. Suddenly, the merit of rock music itself becomes the subject of the trial, raising the stakes exponentially as we watch the tremendous intelligence John Lennon employs to explain rock music to a skeptical, classical-music loving federal judge. I can't tell you how great it feels to witness Lennon use his matchless wit and smarts and musical talent to gain rock the justice it deserves, in a federal case which finally answers that hated question from parents, "What is that noise?" The answer is the perfect title for a John Lennon record-- one more time, in all caps: ROCK 'N' ROLL! For giving the reader this satisfaction, Jay Bergen's Lennon, the Mobster & the Lawyer earns a place on the shelf of any serious music fan.

[1] Here are the Chuck Berry lyrics in context:

New Jersey Turnpike in the wee, wee hours

I was rolling slowly 'cause of drizzling showers

Here come a flat-top, he was moving up with me

Then come waving goodbye in a little old souped-up jitney

I put my foot in my tank and I began to roll

Moaning siren, it was a state patrol

So I let out my wings and then I blew my horn

Bye-bye New Jersey, I've become airborne

[2] Although I am not an I.P. lawyer, I doubt Lennon’s lifting of half a line from the Chuck Berry song would have translated to a huge payday for Morris Levy, the owner of the copyright. Although a borrowed line can be dispositive in such a case, it has to be an especially original and distinctive line, like “Rock Me Amadeus” or “Who Let the Dogs Out?,” and essential to a song’s success. Lennon’s “borrowing” of an obscure lyric from Berry’s song did little to supplant the market’s desire for the original, and if Levy had won the infringement case, he likely would have been awarded nominal damages.

[3] Bergen describes Morris Levy as a “mobster” due to his status as an associate of Angelo “Gyp” DeCarlo and Vincent Gigante, members of the Genovese crime family. In 1988 Levy was convicted in federal court of two counts of criminal conspiracy for his efforts to strong-arm a record wholesaler into paying him for several truckloads of substandard records. Although he received a ten-year prison sentence, Levy died a few weeks before he was required to report to federal prison. Subsequent to Levy’s death, a court ordered Levy’s estate to pay 4 million dollars to Herman Santiago and Jimmy Merchant, authors of the classic Frankie Lymon & the Teenagers song “Why Do Fools Fall In Love?” Santiago and Merchant testified that when they tried to collect royalties for the 1956 hit which sold more than 3 million copies, Morris Levy told them, “Don’t come down here anymore or I’ll have to kill you or hurt you.”

[4] According to Lennon’s testimony, the desired medium for audio recording in the 1970s was 1/4 or 1/2 inch analog tape played at 15 inches per second, commonly shortened to “15 ips,” with many artists using analog tape run at the faster speed of 30 ips. Tape run at the slower 7.5 ips, due to its inferior sound, is intended for home use, and normally not used for master recordings. In an August 27, 2022 livestream on Audiophile 45's channel, mastering engineer Bernie Grundman commented on the relative merits of 1/2 inch v. 1/4 inch tape, noting "I know this isn't very American, but the smaller tape is better!" Grundman added that he preferred the sound of Michael Jackson's Off the Wall, recorded on 1/4 inch tape at 30 ips, to the sound of Thriller, which was recorded on 1/2 inch tape at 30 ips. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6DArqAgLO5s at 38:30, where Grundman notes that "Thriller was not as good a sound as Off the Wall... because that one [referring to Off the Wall] was done on 1/4 inch, and 1/4 inch is always better than 1/2 inch."

[5] Buddy Holly and the Crickets’ signature song, “Peggy Sue” is credited to the late Jerry Allison (drummer for the Crickets) and Norman Petty, Holly’s producer and first manager. According to Wikipedia, Jerry Allison, who died on August 22, 2022, titled the song after his girlfriend and future wife, Peggy Sue Gerron. The original title was "Cindy Lou." Allison was 82 when he died in August, but only a teenager when he wrote "Peggy Sue."

[6] “Be-Bop-a-Lula” was written by Gene Vincent and Donald Graves. Paul McCartney has said many times that this song, recorded by Gene Vincent and his Blue Caps, was the first record he bought.

[7] For more on the right to publicity, see Carson v. Here’s Johnny Portable Toilets, Inc., 698 F.2d 831 (6th Cir. 1983).

[8] From Yale Electric Corp. v. Robertson, 26 F. 2d 972, 974 (C.A. 2 1928).

[9] See Big Seven Music Corp. v. Lennon, 554 F. 2d 504 (2nd Cir. 1977). The “out-of-tune track” on Levy’s “Roots” album was “Angel Baby,” a 1960 hit for Rosie & the Originals. Lennon refused to release this recording on “Rock ‘n Roll” because the band was so out of tune that the band and John’s singing were in two different keys. Levy’s inclusion of the track was a key point of contention in the lawsuit.

[10] A discussion of Lacoste’s tortured and ineffectual attempts to prevent counterfeit tennis shirts from entering the market-place can be found in La Chemise Lacoste v. Alligator Co., 374 F. Supp. 52 (1974).

[11] The trial court found that compared to the “Rock ‘n Roll” album, the “Roots” record sounded crappy even on the good equipment. According to Jay Bergen, District Court Judge Thomas Griesa had such a discerning ear that he noticed that something was slightly off with the playback sound. A technician from the Record Plant checked the equipment and found a worn belt in the turntable.

[12] Author/Lawyer Jay Bergen told me that at the end of litigation, Levy had to hand over all of the unsold copies of the “Roots” album to John Lennon; Bergen also recounted the surprise Yoko Ono expressed when she saw the box of unsold copies of the bootleg. In all, Levy only managed to sell 1270 copies of his counterfeit John Lennon record, and one of those copies went to Judge Griesa, who kept a copy of “Roots” as a memento to what he later described as “my favorite case ever.” The federal judge also kept a copy of the “ROCK ‘N’ ROLL” album, as he was especially fond of Lennon’s rendition of “Peggy Sue.”