Happy Birthday Bob Dylan—84 on May 24th 2025

a selection of veteran music journalist Harvey Kubernik's interviewees help us celebrate Bob Dylan's 84th birthday

The Interviews

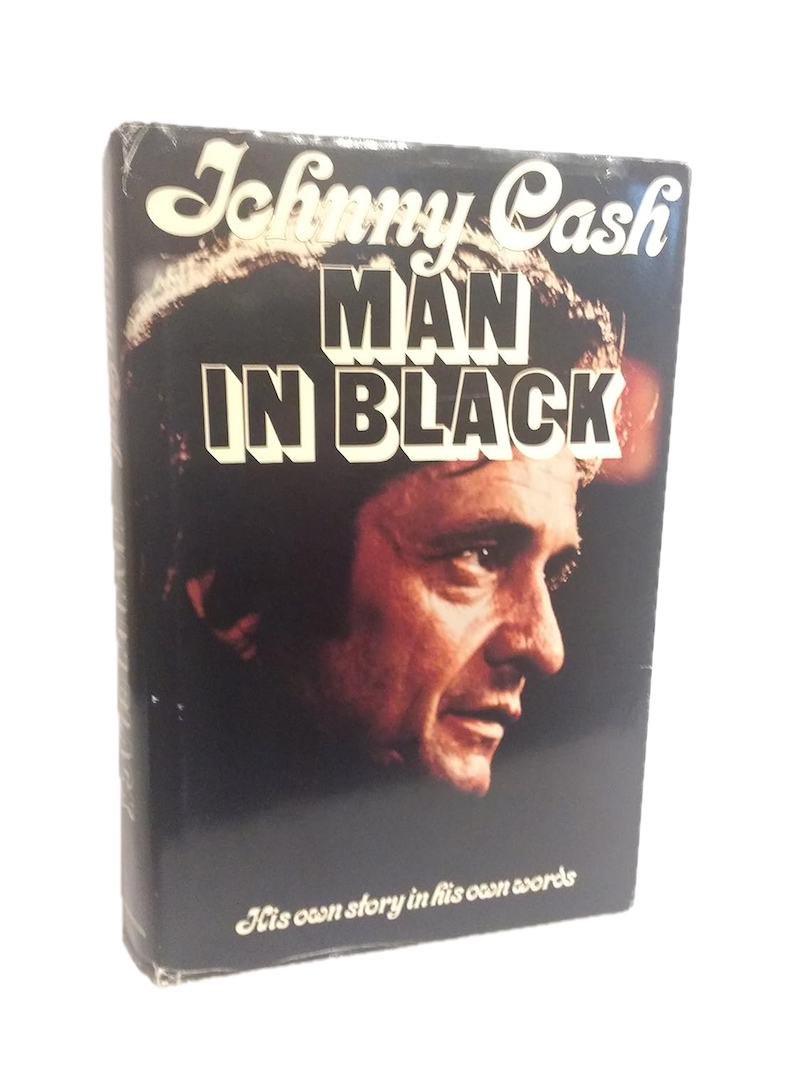

Johnny Cash appeared at a Christian Bookseller’s Convention in Anaheim, California, summer of 1975, there to promote “Man In Black” his newly published autobiography. I caught up with Cash at the Royal Inn and interviewed him for the now defunct UK music weekly Melody Maker.

Johnny Cash: "I became aware of Bob Dylan when the Freewheelin’ album came out in 1963,” recalled Johnny. “I thought he was one of the best country singers I had ever heard. I always felt a lot in common with him. I knew a lot about him before we had ever met. I knew he had heard and listened to country music. I heard a lot of inflections from country artists I was familiar with.

“I was in Las Vegas in '63 and '64 and wrote him a letter telling him how much I liked his work. I got a letter back and we developed a correspondence. We finally met at Newport in 1965. It was like we were two old friends. There was none of this standing back, trying to figure each other out. He's unique and original. I keep lookin' around as we pass the middle of the 70s and I don't see anybody come close to Bob Dylan. I respect him. Dylan is a few years younger than I am, but we share a bond that hasn't diminished. I get inspiration from him."

As a teenager, in the very late fifties, Dylan, then known as Robert Allen Zimmerman, hitchhiked from Hibbing, Minnesota, to Duluth to see Cash and the Tennessee Two (Marshall Grant bass and Luther Perkins guitar) play at the Duluth amphitheater.

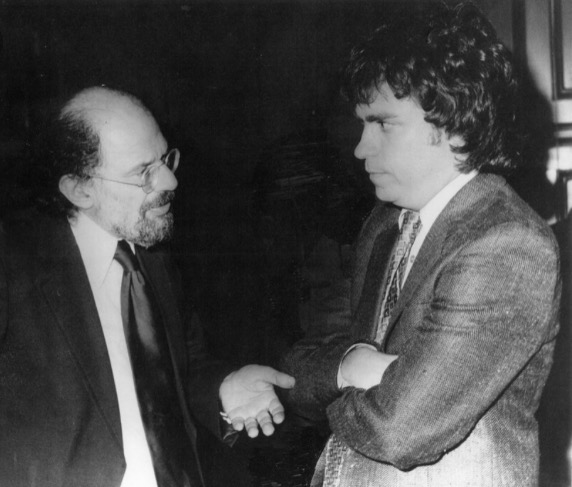

Allen Ginsberg and Harvey Kubernik (Photo by Suzan Carson!)

Allen Ginsberg and Harvey Kubernik (Photo by Suzan Carson!)

Allen Ginsberg: “We [the beat generation writers] were being more candid and truthful than most other public figures or writers at the time. We were switched over to writing a spoken idiomatic vernacular, actual American English, which turned on many generations later.

“Dylan said that Jack Kerouac’s Mexico City Blues had inspired him to be a poet. That was his poetic inspiration. In fact, I remember when Kerouac was asked on The William F. Buckley TV Show in the 60’s. ‘What Beat Generation meant?’ Kerouac said, ‘Sympathetic.’

“So, I think what happened is that we followed an older tradition, a lineage, of the modernists of the turn of the century continued their work into idiomatic talk and musical cadences and returned poetry back to its original sources and actual communication between people.

“I thought the whole 40’s, 50’s literary movement was historically really important, and was kind of a wall built against authoritarianism, that there would be a counter reaction and maybe a police state in America someday, building on the drug thing, and the suppression of literature.

“I visited John Hammond, Sr. in the hospital, on his deathbed, years ago, and our final conversation was about Robert Johnson and Bob Dylan.

“I ran into Hammond in the early 60’s. He knew my poetry quite well. But it was around The Rolling Thunder Review with Dylan that we got more intimate.

“I was on The Rolling Thunder tour, doing a little singing, and I had a whole bunch of new material I had done with Dylan in 1971. During 1971 Dylan and I went into a studio and improvised. I had 40 minutes of music with him. So, I brought that to Hammond in 1975, after the tour. I had a bunch of new songs, and he said, ‘Let’s go in the studio and make an album.’

“I had some musicians who had been with me since 1968 or 1969. David Mansfield from the Rolling Thunder tour and a wonderful musician, Arthur Russell. So, we got together at CBS Studios and did another 40 minutes of music, and later, John Hammond put the two together. He had left Columbia and started his own label, John Hammond Records, to be distributed by Columbia. However, the record didn’t sell. Before I had a chance to rescue the further 10,000 copies, they (Columbia) had, they shredded them, so they were gone, and a rarity now.

“So then in the 1970’s, I began turning on to Dylan. I knew him in the 60’s. He taught me the three chord blues pattern. So, he was my instructor. I began singing in India, Mantra, and in the great 60’s, I began transferring the sacred music idea to Blake, and began transferring that to folk music, and then got together with Dylan in the early 70’s.

“I don’t think I would have been singing if it wasn’t for younger Dylan. I mean he turned me on to actually singing. I remember the moment it was. It was a concert with Happy Traum that I went to and saw in Greenwich Village. I suddenly started to write my own lyrics, instead of Blake. Dylan’s words were so beautiful.

“The first time I heard them I wept. I had come back from India, and Charlie Plymell, a poet I liked a lot in Bolinas, at a Welcome Home Party played me Dylan singing ‘Masters Of War’ from Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, and I actually burst into tears. It was a sense that the torch had been passed to another generation. And somebody had the self-empowerment of saying, ‘I’ll Know My Song Well Before I Start Singing It.’

“Bob Dylan’s film, Renaldo and Clara. Dylan delivers. Well, first of all, it’s Dylan extending himself to the extreme, and including all his friends and all his inspirers, and all his workable companions in a big circus going through America. A musical circus. His mother was along at one point. His kids were along at one point. His wife was along. Joan Baez’s kid was along. So, it was this great family outing trying to hit all the small towns, originally, like in Kafka’s America.

“The Rolling Thunder tour. The traveling circus in Kafka’s America. For me it was great, and to hear Dylan so often, I was able to hear backstage, in the audience, from the side, in the wings, and go out to the furthest seats with a pass.

“He was at a peak of musicality and energy and inspiration. Like ‘One More Cup of Coffee’ and ‘Idiot Wind.’ Which is one of my favorite lyrics with a national lyric. Its great ‘Circles around your skull.’ Really quite manic. It was great to see a band on a rock n roll tour. Rolling Thunder Revue on a grand tour, and see all the work that went into it.”

Billy James: “As an actor, I appeared on Broadway and then television. I saw Dylan in the Village. I met James Dean around the NBC TV studios in New York. I then was a publicist at Columbia Records. In 1961 I taped an interview with Bob Dylan for the company and prepared his first bio. I worked for Columbia as a talent scout as well. I went to Bob’s solo acoustic recording sessions and continued as a writer for the Columbia label.

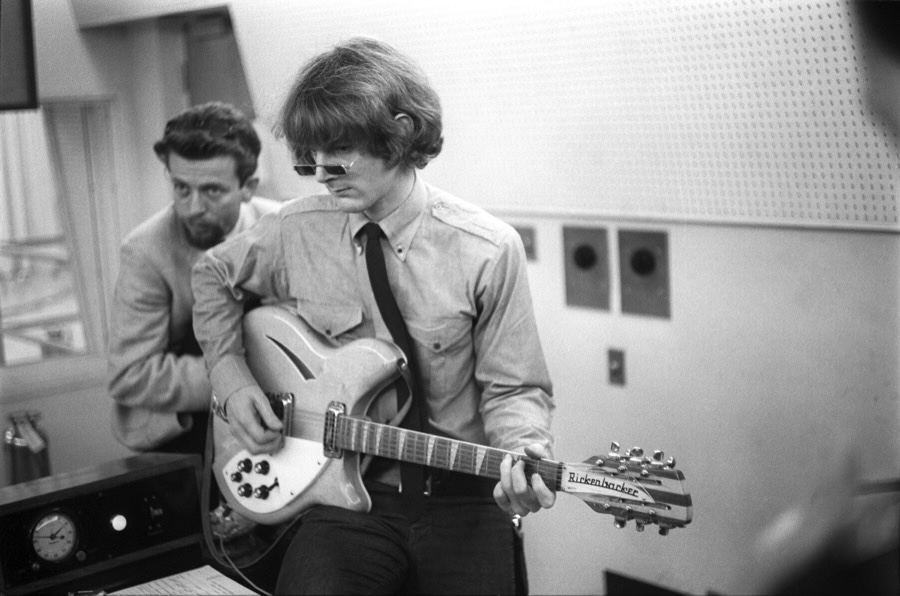

Billy James and (then) Jim McGuinn (Photo by Jim Dickson, courtesy of Gary Strobl at the Henry Diltz Archives)

Billy James and (then) Jim McGuinn (Photo by Jim Dickson, courtesy of Gary Strobl at the Henry Diltz Archives)

“Regarding the early Bob Dylan that I met, I wrote an article for the weekly edition of Variety when I worked at Columbia Records. My headline ran ‘Folk Fans Find a James Dean.’

“On January 1, 1964 I moved to Los Angeles and worked for the company at their Sunset Blvd. offices. At the time I was Manager of Information Services for Columbia Records. I met the Byrds in November 1964. Terry Melcher invited me to a session. We had fabulous times together. As for the Byrds, I was on the dance floor with everybody else at the nightclub Ciro’s. Agent Ben Shapiro got them on Columbia through his client, Miles Davis, and Terry was assigned to produce them. I wrote the liner notes for their debut album Mr. Tambourine Man.

“My two heroes at Columbia were label president Goddard Lieberson and talent scout/record producer John Hammond. I developed a crossover marketing and A&R job under them for myself: Acquisition and Development. Once, I took Goddard around Hollywood, after picking him up at Igor Stravinsky’s house up the Sunset Strip between the Whisky a Go Go and Doheny. I introduced Phil Spector to Bob Dylan at the Fred C. Dobbs Coffee Shop on Sunset Blvd. I arranged local press conferences for Bob in 1965, and in 1966 before Dylan performed the Hollywood Bowl. I was with Bob when he did a press conference on December 17, 1965 at one of the Columbia studios. I do remember where some fool asked him how many protest singers there were.

“One of the ways I have bracketed my life as a grownup is to describe my relationship with four people: James Dean, Bob Dylan, Jim Morrison, and Jackson Browne.

Fred Catero: “I was an engineer at Columbia and started in 1962 as a mixing engineer. Roy Halee did most of the rock stuff. I worked with John Hammond on Dylan sessions, and later bookings for Leonard Cohen, Big Brothers & The Holding Company, the Chambers Brothers, Blood. Sweat & Tears, Al Kooper, Mel Torme, and Barbra Streisand.

“The head of Columbia engineering, Eric Porterfield, designed all-tube hand-built consoles from the former radio rooms.

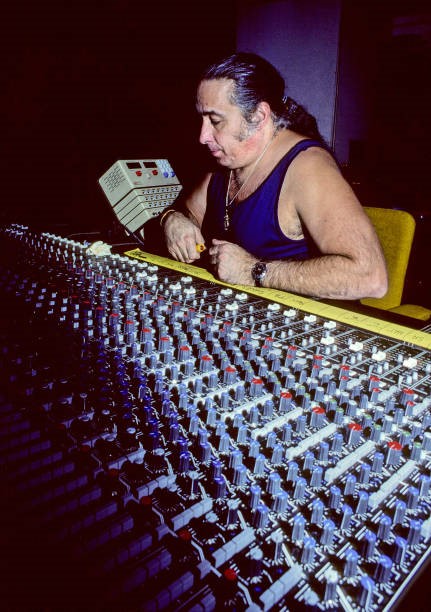

Fred Catero (Wikipedia photo)

Fred Catero (Wikipedia photo)

“Columbia studios had a custom Ampex 8-track, a live chamber and Altec Lansing A7 speakers. ‘The Voice of the Theatre.’ For microphones I used a U47 and maybe a SM57 on lead vocals. The Columbia studios had great natural echo, reverb and leakage. And you wanted that. In fact, it added to the drama. Also, I knew the rooms and where the best place was for piano or bass or the singer.”

Jim Dickson: “I was working with the Byrds. I knew Jack Mass, the local representative of Witmark Music, who at the time published Dylan’s copyrights. Mass along with publisher Artie Mogull was instrumental in getting me the acetate of Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man.”

“The lyrics blew my mind in Bob Dylan’s songs. Victor Maymudes, who was Dylan’s road manager for a while, earlier was doing folk music. I had known him for quite a while. Victor arrived with the first copy of a Dylan album to the West Coast. And he played it for me and I wasn’t that impressed.

“When Dylan came to the Monterey Folk Festival, 1963 or ’64, I went over to a room with Victor and some other people and Dylan had a whole bunch of new songs and he sat there and played them all. Him and the guitar. And that’s what blew my mind. He had one great song after another. He was playing them live.

“It was the first time I met Dylan. The songs became alive in front of me and they were all new songs that weren’t on his first album. He sang about 20 songs and I was just glued to them. I never heard anybody write like that. He was just playing one song right after another. And they were amazing. When I heard “Mr. Tambourine Man” I said, “That’s the best. That could be a hit song.” Artie Mogull just gave me the song. And I put my head down and went after that one with the Byrds.

“Dylan came to the Dick Bock World Pacific recording studio on 8715 W. 3rd Street in Los Angeles more than once. One time with Bob Neuwirth, who played a key role. Dylan also sat there and played the piano with them, got to know them a little bit. Michael Clarke was still playing on cardboard boxes with a tambourine on top. He didn’t have his drums. McGuinn took it over and had a 12-string acoustic guitar with a pick up and Dylan walked around listening to what each person was playing. They were right and he thought they were really charming.

“Then I sent the record to Dylan, we had to get his OK. That’s where Bobby Neuwirth comes in. Dylan and Neuwirth sat on the floor and they wore out the first acetate I sent ‘em. And they listened to it over and over and that’s when Neuwirth said, “you can dance to it.” And Albert was trying to talk him out of it.

“Dylan and Grossman had the finished product but Neuwirth was able to persuade Dylan, “Hey man, it’s a rock ‘n’ roll band playing one of your songs.” And going up against Albert was not comfortable for him, but he OK’d it and we were able to release it.

“The Byrds first heard it all together on the local Hollywood radio station KFWB when they were in a car, a station wagon they bought from Odetta. They had to pull over. At Ciros’s nightclub on Sunset Blvd. Dylan got up on stage with the Byrds and played the harmonica. And he gave me permission to use a photo I took of him and the Byrds on the back of their first LP. I wasn’t really surprised with what he came up with after that.

Dylan and The Byrds At Ciro's 1965 (Photo by Jim Dickson, Courtesy of Gary Strobl at the Henry Diltz Archives)

Dylan and The Byrds At Ciro's 1965 (Photo by Jim Dickson, Courtesy of Gary Strobl at the Henry Diltz Archives)

“David [Crosby] had been anti-Dylan all along, the next time we went to Ciro’s, I see him outside on the sidewalk out front, explaining to some young girl the deep meaning of Dylan and all that stuff. Like he was the expert…

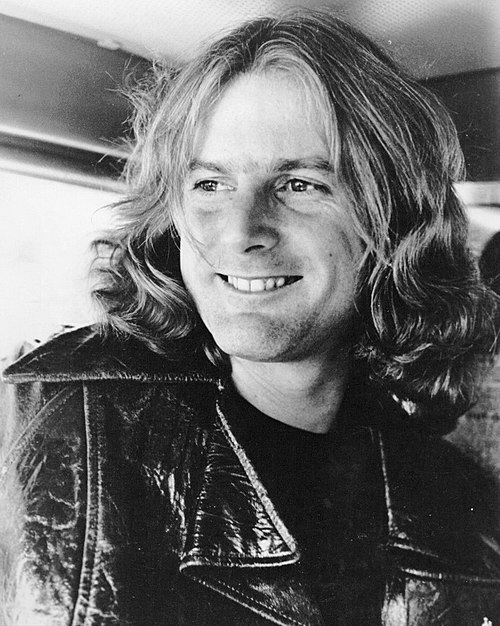

Roger McGuinn: “Our producer Jim Dickson was definitely a large part of the formation of the group and the attitude. It was his pick to do ‘Mr. Tambourine Man.’ He got a demo of it before (Bob) Dylan released it. Jim loved the song. We didn’t get it. He had to bring Bob Dylan around to the World Pacific Studio for us to do the song at all. Dylan came over with Bobby Neuwirth and we played ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ and “All I Really Want To Do’ for Dylan and Bobby, and Neuwirth said, “wow. You can dance to it.’ After ‘All I Really Want To Do,’ Dylan responded, ‘what was that?” And we responded, ‘That was one of your songs, man.’ ‘I didn’t recognize it’ he said. (laughs).

“When I recorded the vocal on the Byrds’ ‘Mr. Tambourine Man” I was trying to place it between Dylan and John Lennon. Dylan’s stuff is brilliant. I coined the term that he was the ‘Shakespeare of Our Time.’ It was like knowing Shakespeare here. Dylan was carrying on [Jack] Kerouac and [Allen] Ginsberg.

Roger McGuinn 1975 (Wikipedia)

Roger McGuinn 1975 (Wikipedia)

“After ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ we just loved Bob Dylan’s writing. I had a real heart for his lyrics and really sang them from the heart. I remember one time Dylan took me aside, I went over to the hotel he was staying at and he said, “You know, I used to think of you as just an imitator but I heard ‘Lay Down Your Weary Tune,’ and listened to that and you’re doing something that wasn’t there before. That’s really good.’ I open my set mostly with ‘My Back Pages.’ I’m kind of saying I’m younger than I used to be. And I’m coming from a young point of view state of mind. And Dylan was too when he wrote it. He said it took him a long time to get that young and he was really digging it. He said all your life when you’re a kid you’re trying to get older. And then he realized he had gotten to a place where the kind of older thing wasn’t desirable encumbering his freedom and liberty. We became his ‘unofficial, official’ band for his stuff. I remember when Sonny & Cher got the hit with ‘All I Really Want To Do,’ Dylan went, “Oh man, you let me down…’ Normally, a writer would be happy to get a hit with his own songs. Who cares who did it? He was on our side.”

“We did Dylan’s ‘Chimes of Freedom’ at the Monterey International Pop Festival in June 1967. I loved the imagery. You can’t pin it down as a peace song, or whatever, but it’s got overtones of that. It’s brilliant. I just identified with it and could relate to it. I love ‘All I Really Want to Do.’ It’s kind of a simple little love song, you know, but it’s got a really sarcastic whimsical attitude. He doesn’t want to be hassled. He just wants to be friends. We changed the arrangement from the 3/4 time to a 4/4 time. We became his ‘unofficial, official’ band for his stuff. I remember when Sonny & Cher got the hit with ‘All I Really Want to Do,’ Dylan went, ‘Oh man, you let me down…’ Normally, a writer would be happy to get a hit with his own songs. Who cares who did it? He was on our side.

“I was driving my Porsche up La Cienega Blvd. and got around to Sunset Blvd. and Jim Dickson, our former producer and manager, he had been fired by the Byrds, shortly before that, he still liked us, or some of us, and he pulled up in his Porsche, and signaled for me to roll my window down. ‘Hey Jim. You ought to record Dylan’s ‘My Back Pages.’ I said, ‘OK. Thanks.’

“The light changed, I drove back up into Laurel Canyon, and pulled out the Dylan album that had ‘My Back Pages’ and learned it. I then took it to the studio and showed it to the guys. And Crosby hated it because he was mostly upset because he wasn’t getting his own songs on the album, and the reason why he left the band. There was a riff in the band, and he wasn’t getting as many as some of us.

“So anyway, I liked ‘My Back Pages’ and don’t remember any resistance from anybody else in the band, just David. And it was a hit and a good tune. I’m really happy with it. It was Dickson’s suggestion and I hadn’t thought of it as a song for the Byrds’ repertoire.

“I liked the wisdom of the song and it’s a very insightful song on the thing that happens when you think you’re so knowledgeable and wise when you’re real young. And then when you get a little older you realize what you didn’t know."

.jpg) Courtesy Rodney Bingenheimer Collection

Courtesy Rodney Bingenheimer Collection

Chris Hillman: “One thing I’ve said before, and what our manager Jim Dickson drilled into our heads, the greatest advice we ever got, and he said, ‘Go for substance in the songs and go for depth. You want to make records you can listen to in forty years that you will be proud to listen to.’ He was right.

Chris Hillman 1972 (Wikipedia)

Chris Hillman 1972 (Wikipedia)

“Here we were. Rejecting Dylan’s ‘Mr. Tambourine Man.’ Mind you, I was the bass player and not a pivotal member. I was the kid who played the bass and a member of the band. Initially all five of us didn’t like what we heard on the Bob Dylan demo with Ramblin’ Jack Elliot. We were lucky. Bob had written it like a country song. And Dickson said, ‘Listen to the lyrics.’ And then it finally got through to us and credit to McGuinn, mainly Jim arranged into a danceable beat. The Byrds do Dylan. It was a natural fit after ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ was successful. Roger (then Jim) almost found his voice through Bob Dylan, in a way, literally voice through Bob Dylan in a sense.

“And then we start doing some Dylan stuff. ‘Chimes of Freedom.’ Great song. ‘All I Really Want To Do.’ At Monterey we included Dylan’s ‘Chimes of Freedom.’ I didn’t realize how beautiful that lyric was until years later. ‘Chimes of Freedom’ is a killer. It’s just one of Dylan’s beautiful songs, and he was just peaking then.

“The Bells of Rhymney” is my all-time favorite Byrds song. What song best describes the Byrds? I would say that one, because of the vocals on it, the harmony. Because of the way we approached the song. We had turned into a band with our own style. We went from doing Bob Dylan material, and then we take “The Bells of Rhymney,” with our own signature rendition of it. It’s not like Pete Seeger at all. It’s our own thing. Michael Clarke was a lazy drummer, but when he was on, he was great. And he’s playing these cymbals. A great experience. I just love that cut.

“The breakthrough record was “Mr. Tambourine Man,” but the breakthrough album was Turn! Turn! Turn! The single record is the most recognizable Byrds song, way over “Mr. Tambourine Man,” with all due respect. That’s the Byrds’ song people always remember. It’s the LP cover I autograph the most.

“The Byrds recorded two tracks from The Basement Tapeson their Sweetheart of the Rodeo LP, “Nothing Was Delivered” and “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere.”

“I have no idea why I got in the mail the two Dylan Basement Tapes songs. I sensed something was good there and I took them to McGuinn.”

Antonino D’ Ambrosio: “In my 2009 book A Heartbeat And A Guitar Johnny Cash and the Making of Bitter Tears,[Cash business music associate] Johnny Western witnessed a Dylan and Cash exchange where Dylan admitted, “Man, I didn’t just dig you; I breathed you.”

“In November 1961, Cash had stuck his head inside the Columbia Records studio when talent scout/A&R man John Hammond was producing Dylan’s debut album, Bob Dylan.

“Dylan was also grateful that Cash would constantly endorse his talents to skeptical Columbia Records executives after the initial weak sales of his first platter, some calling it ‘Hammond’s Folly.’”

Al Kooper: “When I recorded with Dylan on Highway 61 Revisited it used to be on 799 7th Avenue. And that was Columbia Records and they had the studio in the same place as the offices. So, when they moved to Black Rock they then moved the studio further east. So, it was on 49 E. 52nd.

“They duplicated the studio on 7th Avenue. There were three studios there. 2nd, 3rd and 4th floor. And, so they could do a lot more sessions. And they had the same monitors and the same gear at every place. In those days they had rotary pots instead of faders that slid up and down. It was very archaic (but better sounding!_ed). It was also a union shop. With required breaks every three hours. If you were signed to Columbia, you couldn’t record at any outside studio.

“I used to cop Dylan acetates out of producer Tom Wilson’s office. Tom earlier worked for Savoy Records. He was a very bright and high-class guy. He was like ‘what’s happening man?’ That kind of guy. But you knew he was bright and he talked about very erudite things, and he really saved my life that day on that Dylan ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ session.

“Because, he could have…I went to him and said, ‘Man, let me play the organ.’ They had just moved Paul Griffin from the organ to the piano. And I went over to Tom Wilson, and I was invited just to watch, you know. And I said, ‘Man, why don’t you let me play the organ? I got a great part for this.’ Which was bullshit. I had nothing. And he said, ‘Man…You’re not an organ player…’

“And then they came to him and said, ‘phone call for you Tom.’ And he just went and got the phone. And I went into the studio and sat down at the organ. He didn’t say no. He just said I wasn’t an organ player. OK.

Iconic studio shot faithfully duplicated in "A Complete Unknown" : Tom Wilson at the desk, Albert Grossman rear left seated, Kooper far right (YouTube image)

Iconic studio shot faithfully duplicated in "A Complete Unknown" : Tom Wilson at the desk, Albert Grossman rear left seated, Kooper far right (YouTube image)

“On “Like A Rolling Stone,” I was waiting to see what chord they were going to do. There was no music or lead sheet, or anything. I was just playing by ear and I didn’t want to be the one making a mistake because I was doin’ like a rebel run there.

“That was the moment he could have just thrown me out and rightfully so. And you know what? He didn’t. And that was it. That was the beginning of my career. Right then and there. That studio dialog is documented. Wilson is the guy who invited me to the session first of all, which is really nice. You didn’t get invited to Bob Dylan sessions, you know, especially if you were a nobody like I was. And there it was. There was the chance he had to toss me, and it would have reflected back on him because he had invited me to the session.

“I was supposed to play guitar on that record. I packed up my guitar when I heard Michael Bloomfield warming up. It never occurred to me that somebody my age, and my religion could play the guitar like that. That was only reserved for other people. It never even occurred to me that that was an option for someone my age and my color. I had never seen that or heard that up to that day. So, that pretty much ended my guitar playing by and large. I said, ‘well OK, he’s as old as me and he can play like that. I’m never gonna be able to play like that. Thank you, goodbye.’ And, you know, I ended up playing organ on that record, and then I became a keyboard player really that day. So, it was a damn good thing because, you know, that was competition I couldn’t deal with.

“The pianist Paul Griffin. Oh...man…A big influence on me as well! Paul Griffin came from the Baptist church. On Highway 61 Revisited we did the tracks to ‘Tombstone Blues’ and ‘Queen Jane Approximately’ in one day. The best thing I can say about Paul Griffin is take five minutes out of your busy day and get a time where you have nothing to bother you at all. Find a real nice stereo system and sit back and put on ‘One of Us Must Know’ from Blonde On Blonde. And just listen to the piano…And tell me if you can find on a rock ‘n’ roll record anybody playing better than that. And I would really like to hear what your decision is. To me it is the greatest piano achievement in the history of rock ‘n’ roll. I don’t hear anything than him playing the piano when I hear that record. And I’m thrilled that I’m playing organ but I’m embarrassed. And I think that Dylan should be embarrassed too. ‘Cause Paul just steals that fuckin’ record. It’s the most incredible piano playing I’ve heard in my life. If you’re a piano player try playing that note for note. It’s just incredible.

“I played the organ on ‘Like A Rolling Stone.’ Paul Griffin on piano was so brilliant. He plays amazing things. And the thing that is really eye-opening about it, are the drums. Bobby Gregg, who had a hit record with ‘The Jam.’ Besides Michael’s playing, you can really hear the drums of Bobby.

“On Blonde On Blonde I was astounded by everything. (laughs). I was astounded by the musicians. I mean, astounded by the musicians. Do you know at one point in ‘Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I’ll Go Mine)’ Dylan refused to overdub things. He just wanted to play it live right there and forget about the fact that you could overdub. OK. I said to Bob, ‘horns would be really nice on this.’ (imitates marching horn line). And he said, ‘well…There’s no horns here.’ So, Charlie McCoy says, ‘I play trumpet.’ So, Bob said, ‘I don’t want to overdub anything.’ So, Charlie said. ‘I can play the bass and the trumpet at the same time.’ And Bob and I looked at each other, and Bob was laughing, and Charlie said, ‘no really, I can.’ He played the bass and the trumpet at the same time.

“There are a few reasons Blonde On Blonde holds up. The main reason is the chemistry of the participants. That’s the main reason. And the other reason would be the songwriting. I think the combination of those two things could make if they were as wonderful as those two were on that record it could make any record last a long time. The credit has to go to (producer) Bob Johnston. It was his idea. He had tried to get Dylan to record in Nashville in late 1965. He knew about the chemistry. And I also think he felt more comfortable there because he lived there. And he knew all the musicians intimately.”

“I had the benefit of whatever time differences there was between Highway 61 Revisited and then the Blonde On Blonde record of being a better player. So that was helpful. I knew how to operate the machine a little better, the Hammond organ. And then I ran into a methodology thing. Because in New York I was raised, all the sessions I played on and everything, it was three songs in three hours. I had never seen what they did in Nashville. They just hired the musicians and they were booked until we were done that day, or night, or whenever it was. They didn’t have any other distractions, there were no breaks, just whatever it was and I had never worked like that in the studio, but it was a big eye opener for me. During the day, Bob had a piano in his room and I would go up to his room and he would teach me the song and because there were no cassette machines in those days, I would play the song over and over for him and he would write the lyrics. Actually, I think of myself as the music director of that album. ‘Cause that’s what I did.

“I learned after I did Highway 61 Revisited that these sessions were going to be heard for a very long time. So that one time during Blonde On Blonde I started thinking, ‘You know, wherever my hands move next it’s gonna be around for all time.’ I started thinking like that and I said to myself ‘Will you please shut up and just do what you do.’

“It can completely freak you out if you thought like that. And I had that thought for one second, and then I said, ‘I really can’t think like this and do this job.’

“So, yeah, but not on Highway 61 Revisited but on Blonde On Blonde I did have that thought.

“The other thing was, by then, Bob and I were friends. We had spent a lot of time together. Off hour time together. Just sitting around bars and shit like that. Going to the movies and all this kind of stuff, so it was a much more comfortable situation and Robbie Robertson came too. Robbie and I split a room together at Roger Miller’s King of The Road Motel. So, Bob brought Robbie and I for his comfort level, rather than just go in there cold. You know what I mean?

“No one talks about Bob’s piano playing because they don’t know. Bob had a very unusual way of playing in that he didn’t use his pinkies. So, both his pinkies were up in the air when he played the piano and that’s very interesting to me. It was very interesting looking to watch that. I used to really get a kick out of that.

“I had played live in 1965 with Robbie and Dylan. The Hollywood Bowl and Forest Hills in New York. The Hollywood Bowl show was the only place where Bob played where he wasn’t booed. How ‘bout that?

“In 1966 I got the itinerary for the Dylan tour and I said to myself ‘I can’t do this.’ They were playing Dallas, Texas. 2 years after JFK. I said to anybody who would listen, except Bob, of course, ‘You’re going to fuckin’ Dallas. I don’t want to be the (Gov.) John Connally of rock.’ That was my line (laughs). I thought I’d be sitting in the fuckin’ front seat and I’ll get killed.

“Sometime in 1986, Bob called me and invited me to an event at Chasen’s restaurant in Beverly Hills. He was receiving an award. [Founder’s Award from the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers] He told me to meet him at the restaurant. Then he called and said to meet him around the block. The limo pulls up and I get in and Bob is in the back seat with Elizabeth Taylor.

“I’ve recorded three Smokey Robinson songs. One of my favorite things is when I called Dylan one day and said, ‘Hey…What are you doing?’ And he answered, ‘Eating a piece of toast and listening to Smokey Robinson...’”

Bob Johnston: “After [Tom Wilson produced ‘Like A Rolling Stone’] I was working with Bob Dylan in New York on Highway 61 Revisited and I flew in Charlie McCoy from Nashville, introduced him to Dylan, and the first thing we cut was a version of ‘Desolation Row,’ with Dylan on acoustic, Charlie on electric, and Harvey Brooks on bass.

“I was standing by the sound board and I said to Dylan ‘Listen man, you ought to come to Nashville sometime. I got a fix up down there with no clocks and the musicians are fuckin’ great.’ ‘Hmmm.’ He’d never answer you, just go ‘hmmm’ like Jack Benny.

“So, I finished Highway 61 Revisited and then Dylan called me about six months later and he said, ‘I got a bunch of songs. What do you think about going to Nashville?’ ‘That’s what I was talkin’ about!’

“In 1966 we went down there for Blonde On Blonde and the first thing was beautiful. He said, ‘Well, I got an idea…’ He stayed out in the studio 10 or 12 hours. He never left it. He’d eat candy bars and drink milk shakes and all, and nobody does that much.

Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash, Bob Johnston (Photo by Al Clayton, Courtesy of Sony Music)

“I sent the musicians away and told them to do anything you want to and be in phone contact. Don’t go home… you can be in the studio down here if you need some beds or something. About 2:00 in the morning Dylan came out of the studio and said, ‘I got a song, I think. Is anybody left here?’ First thing we did was ‘Sad Eyed Lady Of the Lowlands.’

“I told everybody if they quit playing, they were gone. It didn’t matter because I could overdub anybody but Dylan. But if you quit with him, you’ll never hear that song again. And he’d go to the count and play something else. So, they came out and got all around. And Dylan said, ‘it goes like this. C, D. G.’ And then he went over the thing and they said, ‘Man, we haven’t heard this thing.’ ‘I said that’s right. The first one who misses just walk out of the room. Don’t stop.’

“And he went out there and started counting off, and that’s another thing. Nobody ever counted off for Bob Dylan. Every other artist in the world that I’ve been around has a drummer or somebody else counting. He went 1, 2, with that foot and it was gone. When we got through he said ‘let’s hear it back.’ And he came in the studio and played back ‘Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.’ 15, 16 minutes. And that was the first thing that we did for Blonde On Blonde. And from then on it just went up and up and couldn’t go up any higher and higher. I think that’s one of the best tracks ever cut along with ‘Desolation Row.’

“Dylan and I were notorious for using first takes. I don’t see any sense in doing it over and over. They knew what I wanted them to play not what I gave them. That’s why they were there. When I started with Dylan he said, ‘my voice is too loud.’ Good enough. So, I turned it down. Then I’d turn it up. ‘Man, I can’t hear myself’ and had that voice out there. Finally, we got to the place where he said ‘I can’t hear myself.’ ‘Cause I’d brought it so low. So, I told him I’d take care of it and never asked him about it anymore and turned everything up and had that voice out there.

“I would place glass around Dylan for recording. He had a different vocal sound. I didn’t make his different vocal sound. He always had different sounds on. I ndnnever wanted to be [Phil] Spector. “

“I always had 4 or 8 speakers all over the room and I had ‘em going. The louder I played it the better it sounded to me. This is the way I really did it. As a songwriter, I wrote songs, too. Dylan changed the world. Every song he did I loved. I was a Dylan freak and I knew he was changing the world. I knew he was changing the society as we know it.

“I’ll tell you something else I did with Dylan, and recording Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash. Everybody else (at the time) was using one microphone. Which means you have to sacrifice something. If you’re gonna have a band you can’t have the band playin’ full tilt, if you’ve got him in the middle because and can’t understand everything with different people in there raising the guitar up, raise the drum up, and do shit like that.

“And what I always did was that I had three microphones because he was always jerking his head around, and I put the microphone on the left, center and right and it didn’t matter where in the fuckin’ room he went. And then I’d mix and start on the left and go all the way over on the right. So, I’d usually have the piano on the outside left, without any echo. And then I’d put the echo on the right side. And then I’d have one of the guitars on the right and put the echo on the left. And then I’d match it all alone and brought up everything even so they could fight it out. And then that’s the way the band was.

“They didn’t have to raise this and lower this, and 15 people sitting around doin’ all that shit. The band was there and he was full tilt. Then you could go any place in the room and understand him. And I never heard another word from him about anything.

“What I did was put a bunch of microphones all over the room and up on the ceiling. I would use all those echoes when everything got through and I could do that as much as I wanted. I wanted it to sound better than anything else sounded ever, and I wanted it to be where everybody could hear it. And I don’t know what Dylan would have been if he stayed in New York with those people, and been mixed like that. And I know he would have never done that shit like he did in Nashville."

Andrew Loog Oldham: “I worked as a press agent for the Beatles, Chris Montez, Bob Dylan and the Little Richard/Sam Cooke/Jet Harris 1962 tour before I met the Rolling Stones in 1963. I worked for fashion designer Mary Quant in 1960 when fashion was the pop business - the only pop Britain had. It was a time when American Cinema gave us hope and attitude, and the pill gave us time and disposable income.

“In 1963 I managed to score some press for the still-unknown-folk singer in England. I was doing PR in January ‘63 and bumped into manager Albert Grossman at the Cumberland Hotel, Marble Arch. His client, Bob Dylan was in London to play a minor role in a BBC2 television drama, Madhouse on Castle Street. He would eventually perform two songs: ‘Blowin’ In The Wind’ and ‘Ballad Of A Gliding Swan.’ A fiver for ten days of work. It was written by Evan Jones and the director was Philip Saville. I managed to get Dylan into Melody Maker. Thanks to Max Jones or Jack Hutton. They were doing me a favor-Nobody else cared…Dylan and Grossman were very happy together. They acted like they knew something we didn’t know yet. Grossman also managed Peter, Paul & Mary.

“In a different realm it was like being in a room with Dylan and Grossman. There was this conspiratorial thing that was so powerful; you knew it had to work. Mother was wrong. I had not had to get a regular job. I was having the time of my life. And then I met the Rolling Stones and said hello to the rest of my life....

“I’d always regarded Sam Cooke and Elvis Presley, and later Bob Dylan as the real self-producing artists of the era. Sinatra and Bing Crosby had to be the Guv'ners - Keith Richards and I got to watch Mr. Sinatra record, that was an education in form and producing thyself. – To know thyself and how to dress yourself in sound, song and polish every word so that it belongs. It places you above anything that can be deemed the A&R domain. Dylan did look back. He looked back at the Beatles and the Stones, went hmmm, went into the studio and changed the goal posts.

“I've always preferred the idea of Dylan and what he did for America and the world with word and imagery, as opposed to the actuality. I loved his late seventies on stage Latin cowboy shtick; I loved Oh Mercy and "Gotta Serve Somebody", but there were a lot of years in there where he seemed in need of a life. I loved him forever young once again in those January ‘98 shows with Van Morrison. But like Bruce Willis, I like the idea rather than the detail. They are both American heroes and I respect their cause and effect on American and wannabee lives. They give hope and they explain in a few chosen words. That's not a bad gig to get paid for."

Robbie Robertson: “One of the things that I really took away from visiting the Brill Building with Ronnie Hawkins, was Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman, Leiber and Stoller, Otis Blackwell, and Titus Turner, who was an incredible character.

“Anyway, one of the things I really got from them, because the obvious thing was that they tapped into something that felt good. But it had to feel good. The song could be about anything but it had to feel good. And I was like. ‘Wow…’ It would be one of the guys sitting at the piano playing. ‘Let me think of something. What about this?’ And they would start to play something. I was studying. So, coming in the back door of something, that when you start this thing if it doesn’t feel good then stop right now.

“Then, the other door was Bob Dylan who it wasn’t about that. It was about emotion and an energy, but it was really about saying something. It wasn’t about ‘these words could be anything.’ No. No. It was specific. So, to me it was rebelling in a beautiful way against this other thing.

“There was a thing that happened between Bob and the Band on stage that when we played together that we would just go into a certain gear automatically. It was like instinctual, like you smelled something in the air, you know, and it made you hungry (laughs). It was that instinctual. And the way we played music together was very much that way. And whether, we were playing in 1966, or 1976, or when we did the tour together in 1974, we would go to a certain place where we just pulled the trigger.

“It was like ‘just burn down the doors ‘cause we’re coming through.’ And it was a whole other place that we played when we weren’t playing with him. So, it was like putting a flame and oil together, or something. I don’t know.

“Well, we didn’t change. [laughs]. I don’t know that this has ever happened to anybody else. And it is a phenomenon. And that’s why I feel bold enough to refer to it as a musical revolution. Because the world came around. We didn’t. We didn’t do anything that much different. [laughs]. We just went out there and hit it between the eyes. And now people have a completely different reaction to it. And I thought ‘that’s kind of incredible that the world actually came to this place, you know. And I don’t know who else has been through that.

“It’s interesting and it’s one of the things I talked about in my keynote speech that I had to make at this [2002 SXSW] conference. It’s really a very interesting experiment to see, or go from something that people were so adamantly against this music, and that we didn’t change nothing, and the world revolved, and everybody came around and said ‘this is brilliant.’ That was very interesting to see everything else change around you.

“We did have the experience with Bob Dylan and in doing The Basement Tapes with the songs that were supposed to be shared with other artists to record. It was because so many people recorded Bob’s songs and we were hooked up together, you thought ‘Oh. That’s part of it.’ And how that struck me I didn’t think about it in writing the songs or making the records that other people would do. This was a very interior thing. This was a thing between the five of us in the band. Something that we had collected over ages and pulled it together and made this gumbo.

“Bob already had such a track record that you thought people are going to be drawn to this. If he put something out there for people to record, people are going to be drawn to this. It just seemed to me that this was something he’s already established. So, it wasn’t after we sent out these songs and everything and it wasn’t me saying this is exactly what it was.

“Bob was involved in it. Garth was involved in it. Right? And part of it was just in fun. You know, we would record a song like ‘You Ain’t Going Nowhere.’ And Bob would say. ‘Whatta you think. Ferlin Husky? Right?’ And it was half kidding around and half meaning somebody is going to but with the way that he is and the way that he thinks too Bob that he could insist on sending that song to Ferlin Husky first. You know what I mean? Just because he would do something like that. But when we said ‘OK. We’ve got to pull some of these things. We were recording a lot of stuff. We were covering songs and just having fun. And then every once in a while, there would be an original one in all of this.

“And when we were doing this not with Bob, this was the germs and the idea and the beginning of Music From Big Pink. That was happening kind of in the back room too. So, when we chose those songs to send out, we were choosing what we liked. We were kidding around. I didn’t notice Manfred Mann could do a really great job on ‘The Mighty Quinn.’ I didn’t know that. But we were saying ‘that ‘The Mighty Quinn’ thing has something to it.’ It really was what felt right in putting that collection together.

“When we hooked up with Bob Dylan it was made clear to Bob and to Albert [Grossman] ‘this is a whistle stop for us.’ We are on our own path. We’ll do this in the meantime but we’re going to do our own thing. We’re not here. We’re here to do this. Right?

“After we did the thing with Bob and he wanted to do more. But he had this accident and so then, and I say this in the book, Albert had no idea what we were or what we could do. No idea. He liked us. He thought it was really interesting what we did with Bob. But he said, ‘I think I can get you a deal for doing an album of instrumentals of Bob Dylan songs.’ So, I said, ‘All right. Let me talk to the guys about that.’ (laughs). And I thought, ‘Albert has no idea.’

“When we recorded Music From Big Pink Albert was astonished by the results of that record. And he so embraced it and made it his own and all that other stuff vanished. He was like ‘I knew it all along.’ It fit so perfectly into his scenario.

“Bob and the Band were so close to Albert. We had been through everything together. We were like war buddies. And we had gone to the edge together. And because we had done all that stuff and The Basement Tapes, and through all of this, still had no idea of what this was going to be when we did it. That was thrilling.

“All of a sudden it seemed like a good idea in 1975 to release a double LP of The Basement Tapes. I can't tell you why or anything. It just popped up one day. We thought we'd see what we had. I started going through the stuff and sorting it out, trying to make it stand up for a record that wasn't recorded professionally. I also tried to include some things that people haven't heard before, if possible. Whether it went top ten or not didn't concern me. I just wanted to document a period rather than let them rot away on the shelves somewhere. It was an unusual time which caused all those songs to be written and it was better it be put on disc some way than be lost in an attic.

“[In 1976] At The Last Waltz, we all tossed our thoughts into the hat and then we would try stuff, and if it felt right, then we just did it. It was one of those things like letting some higher power make the decision, because the proof was in the pudding.

“Bob wanted to do stuff that was connected with our origins together, which is why we did ‘Baby Let Me Follow You Down,’ which we played back then, and ‘I Don’t Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Had Met).’ And having a thread going back to 1965-1966. And because it felt real. And obviously ‘Hazel’ and ‘Forever Young,’ because us working together on the Planet Waves thing.

“So, it was trying to find a connection, and not just do something that nothing to do with anything. We wanted it to have some thought. Nobody suggested ‘Hazel’ but Bob said I think we should do ‘Hazel.’

“It was like we’ll do some of the stuff from the 1965-1966 period. We’ll do something from Planet Waves. We had just recorded it a couple years earlier. And in mixing it up we ran through a bunch of crazy ideas too. Like Bob said ‘should we do a Johnny Cash song?’ And he would start singing a Johnny song and we all knew this was never gonna fly. But it would be fun to play it. We’d play through it and say, ‘No.’ But all of this stuff, it was really like throwing things up in the air and see where they would fall. But Bob said, ‘you know one song I think we should do is ‘Hazel.’ We were like ‘Really? OK. Let’s do it.’ And we ran through it and it felt pretty good. ‘All right.’ But we knew we wanted to do ‘Forever Young.’ Because it connected to the occasion with all the people there and this generation and all of this stuff.

“At The Last Waltz, the songs from Planet Waves became a whole other thing live. And the difference in the passion level is just extraordinary.

“Planet Waves was completed in three days. Dylan may be a fast worker but for The Band, who take infinite pains, that's hectic. We know the technique very well. We've been playing with Bob for years. There are no surprises involved. We did it and it was over before we knew it. We managed to get several things off very well for such a short time. But it went by so quick and we were preoccupied with the tour and all the other things that go with it. With all the decisions to be made and all the how, when and where, that album really took a back seat.

“I moved out to Malibu and Bob and I were hanging out. We’d been talking about a tour for years. All of a sudden it seemed to really make sense. It was a good idea, a kind of a step into the past. We felt if there’s anything that everybody expects us to do, that’s what it is. We quickly decided it was a good idea and a new day. The other guys in The Band came out and we went right to work. We started rehearsing anyway, so we thought we’d do the Planet Waves album and get back to rehearsing, and that’s exactly what we did. . . “

Larry LeBlanc (Canadian Music journalist): The connections of Bob Dylan to Canada are many starting with him making his Toronto debut—twice in 1964. His first appearance, in February was a taping of the CBC TV show Quest followed by his Toronto concert debut on Nov. 13th, 1964 at Massey Hall.

“It was Toronto booking agent Mary Martin, then working for Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman in New York, who introduced him to Levon and the Hawks, the former backing band for Arkansas rockabilly artist Ronnie Hawkins who had settled in the city. In 1965, Dylan returned to Massey Hall with backing by the group to the audience sound of scattered booing.

“Dylan again returned to Massey Hall in 1980 seeking to release a live album and concert film titled Solid Rock,but CBS rejected it. However, the video and soundboard of the final show leaked and were officially released, most notably across two discs of The Bootleg Series Vol. 13: Trouble No More 1979–1981.

“It was Toronto-based Ian Tyson of Ian & Sylvia, also managed by Albert Grossman. who turned Dylan onto cannabis in New York. Then on August 28 1964 Dylan introduced the Beatles to weed at the Delmonico Hotel on Park Avenue, near Manhattan’s Central Park.

“In 1970, Dylan paid tribute to Toronto folksinger Gordon Lightfoot in recording his song “Early Morning Rain” for his double Self Portrait album on Columbia.

“During a 2011 interview, Dylan ranked Lightfoot near the top of his list of favorite songwriters.

“In 1972, Dylan and Lightfoot paid a surprise visit to the Mariposa Folk Festival in Toronto on July 16, 1972. They watched as Neil Young took over Bruce Cockburn’s set.

“Lightfoot was a guest on Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue at Maple Leaf Gardens on December 1, 1975. Following the show Lightfoot invited Dylan and the entire cast, including Joan Baez, Roger McGuinn, Joni Mitchell, Ronee Blakely, Ramblin' Jack Elliott. and Bobby Neuwirth to his house in the Rosedale neighborhood of Toronto for a lively party that was filmed.

“In 1986 Dylan shyly inducted Lightfoot into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame at the Juno Awards. Quoted in a post on faroutmagazine.co.uk after Lightfoot's death, Dylan said “Every time I hear a song of his, it's like I wish it would last forever…”

Charlie Daniels: “When Bob Johnston moved to Nashville in 1966, he called me and said, ‘Why don’t you come to Nashville?’ And I always wanted to live there and packed up in 1967. He had just done Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde. All the good things that happened to me in the early days were because he was a cog in the wheel.

“In ‘67 and ’68 Bob produced the albums John Wesley Harding and Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison. Bob had gained credibility. He was also at the same time, bringing Dylan and Leonard Cohen into town who had never lived here.

One thing that needs to be said about Bob Johnston and bringing people to town like Dylan and Leonard Cohen. There was skepticism about Bob coming to Nashville because he was taking the place of a legendary producer, Don Law, who was an institution in town.

“Here’s this guy Johnston from New York, who had been doing Simon & Garfunkel, Bookends, Dylan, and now Leonard Cohen, who were not really thought of as being country. But the first thing Bob did when he came to town was to do a number one song with Marty Robbins. And in ‘68 produced the albums John Wesley Harding, Flatt & Scrugg’s The Story of Bonnie and Clyde, and of course, Johnny Cash’s live album at Folsom Prison.

“He had gained credibility. He was also at the same time, bringing Al Kooper, Dylan and Leonard Cohen into town who had never lived here. Dylan recorded in Nashville in 1966 for a while, but it was he’d come to town, do his stuff, and leave. Dylan happened to record in a studio in Nashville and worked in it.

“And, hassles with long hairs, prejudice, racism, didn’t exist in our world. In the sixties everything was pretty much in the throes of a lot of upheaval. This was back in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s salad days, when he was going around, doing things that a lot of people didn’t understand it or didn’t get it. I was in Nashville when Dr. King was assassinated in Memphis. The thing was, when you’re goin’ in to make music that is a whole other thing.

“Nobody wanted to work in the big [Columbia] studio until Bob Johnston came to town and basically took it over. Nobody else wanted to be there. He worked with it, got engineers he enjoyed working with like Neil Wilburn, and he actually brought an engineer from New York with him when he first came down.

“The Columbia Studio was union. In Nashville, in the studios, you had to have the machines to be a certain distance away from the boards so the engineer could not work them both. But the thing I remember mostly about Studio A., the big studio, it was the new studio. The old studio, the Kwansit Hut, was the legendary studio where the hits had been cut. Everybody wanted to work in that room.

“With people like Cohen and Dylan…Most of the Nashville sessions, the country artists they would bring a demo in, they’d play the demo, you play it like the demo, you may change a key on it, but basically it’s gonna be the same thing, how they want the demo. So, you’re playin’ pretty much inbounds.

“With Leonard and with Bob Dylan, and it was on a Dylan, and Charlie McCoy was the band leader. And how much do you want him to play? How many bars? How much do you want him to do? And Dylan replied, ‘all he can.’ Well that really describes what this is all about.

“Cohen and Dylan were singers and songwriters. They write their songs. They weren’t coming in from a music publishing company. It was a lot different because there is no hurry. We went into the studio. Like with Nashville Skyline we had about fifteen sessions booked to do it and probably only used half of them and it was over. Everybody got so into what they were doing. If you listen to Dylan, the stuff before and after, Nashville Skyline stands out. It’s a different kind of record. The material was a little different and dealt with different themes.

Nashville Skyline and John Wesley Harding are two different records to me. The Nashville Skyline record was a departure for Dylan. It was just so different than anything I had heard him do. ‘What else you got Bob? We got this one done.’ And of course, Dylan is a big first take guy. If you can get it on the first take that’s how he wants it. And I like that about him. I’m the same way."

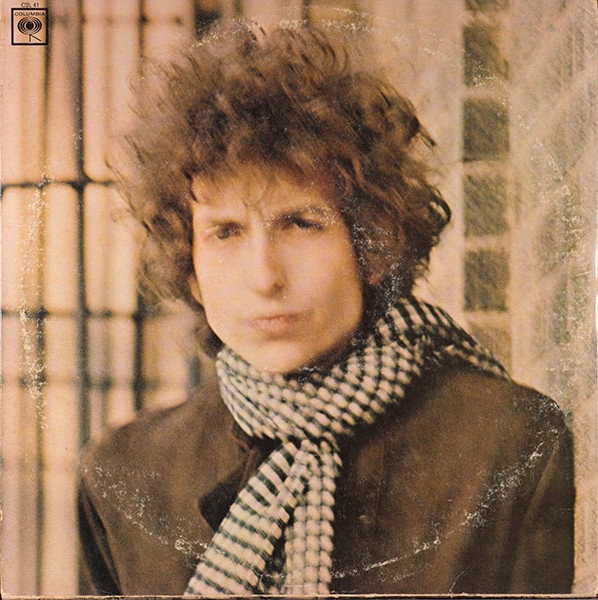

Jerry Schatzberg (photographer): "Everybody was trying to figure out what kind of drug trip we were trying to portray on Blonde On Blonde cover as it was out of focus. Nothing to do with that. It was January. Dylan had on a light jacket and I just had on a light jacket and a number of the images while we were moving around were moving, you know. So, they were blurred a little bit. I must say Dylan chose that one and I was delighted. I knew there are a number of other good images from that shoot that were quite good which I use now. For a while I used just the Blonde On Blonde cover. But now, at shows and different places, I show them. They are quite good and absolutely sharp. But people thought we were trying to say something more than what we were.

“I think any photographer that photographs another person tries to capture that person as best he can. By this time, I knew Dylan quite well. I’d been photographing him for about a year. We’d hang out together and go places. When you’re in that kind of a relationship you are getting into somebody’s soul.

“That as one thing. A lot of people want to know where it was photographed. To the best of my recollection, it was a meat packing district in Manhattan which I had gone over a number of times to find out exactly where and it just doesn’t exist anymore. So it was either a building that was torn down or totally surfaced and I have no idea. Sony is now in the process of doing a search on a number of albums and where they were shot in New York. Two weeks ago, we went down to the meat packing district with a camera crew and Sony looking for it. But we found a couple of places they might have. I liked the meat-packing district in contrast to Dylan. I felt that would be a good place to shoot. The first set of photographs I took of him were in 1965 in the recording studio with a Nikon. In color I used a Hasebland camera.

“I had asked Al Aronowitz who was in my studio who was talking to a disc jockey that I knew and I was probably photographing somebody. My ear heard them say, ‘Dylan, I saw him yesterday. I’m quite friendly with him.’

“I said, ‘Hey. The next time you see him tell him I’d like to photograph him.’ The next day I got a call from his wife Sara. Who I knew before she even knew him. She was the one who kept telling me about Bob Dylan. Sara said to Bobby that I would like to photograph you’ and he said ‘OK.’ And I replied, ‘I’d love too.’ She gave me the address where they were recording Highway 61 Revisited.

“Next day I went over and was welcomed. He even let me hear some of the sides they were doing and comment on it. I must say I was a little intimidated at first but they really made me quite at home.

“I had photographed a lot of people. The Duke of Windsor when he was once the King of England. I don’t have to be intimated by anybody.

“But, you know, when you come across a talent like Dylan…I didn’t catch on to him at the beginning. I was listening to him and it was Sara and Nico from the Velvet Underground they kept yelling, ‘Genius.’ I was very impressed what I heard and what he was doing. He was funny. We used to go to my club, Ondine’s. I was a stockholder, sit at the bar and hang out.

“Because the first shoot was during the Highway 61 recording studio and, of course, that’s his kingdom. He could do anything he wants because he’s comfortable there. He was also comfortable around me because of Sara and Al. I got the photographs in and wanted them to like them and they did. And that’s when I wanted to get him into my studio where I had more control. And once he came to my studio, there was nothing he’d say no to, basically. I’d find a prop that I might have used in a previous photograph, I’d give it to him and he’d do something with it. He was just very cooperative and he felt at home too. My studios and film sets are always that way. I want people to feel comfortable and I want them to do something usually a little bit different from what they do in real life. I make them comfortable and they do it.

“What struck me during re-visiting the experience was that it was quite good. I photographed Bob’s first son with Sara. I photographed a lot of things that were very personal.

“1966 was a special time. I mean, it started in the fifties with the beat generation. 52nd Street jazz. The poets, Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti were talking to the people. Listen to the rock music in the early and mid-sixties. It was really about the people. It was the revolution of saying ‘we’re not getting into what we did yesterday. We want to do something different.’

“The special time, and a bit later, 1967, the Summer of Love. LIFE Magazine putting rock groups in the pages and cover.

I don’t think it happened after Dylan’s motorcycle accident. I think it really happened at the start of the fifties. With the beat generation and poetry that went on. Allen Ginsberg and Ferlinghetti and all those people. They were saying ‘you don’t have to write things the way they used to be. You can do this and you can change.’

“I think that just crept into the music, And of course, maybe the Beatles and all that music coming. It wasn’t exclusively America. It really started in London England where the music was coming through differently. It all started with our own rhythm and blues. It took the French to tell us that we started jazz, you know. But we did have those roots. And I think you can go back all the way to there. Like the rock ‘n’ roll 1952-1960. The early rock people, the blues recording artists. Those artists.”

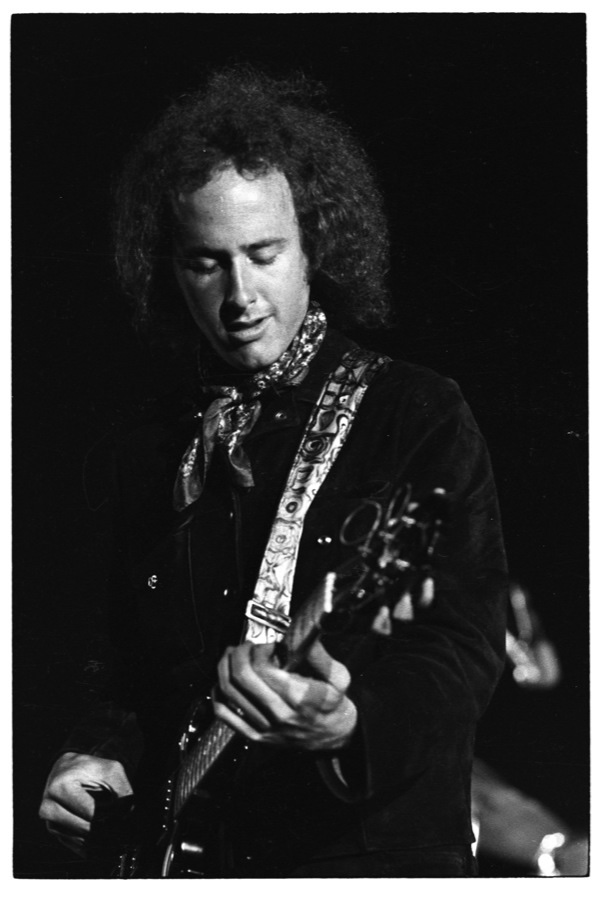

Robby Krieger: “I saw Dylan perform in 1963. I was in high school in Menlo Park, near San Francisco. There were some guys there from Boston and New York in the dormitory with me and they were into Bob Dylan. I had never heard him before. They had his debut LP. So, they played the first album and I got totally into him.

“On Dylan’s first album I really liked his guitar playing. I thought he was a great fuckin’ acoustic player. He did some stuff that was pretty damn good. And his harmonica work. I had never heard anyone play harmonica like that. Not a blues harmonica player sucking in the notes. I was amazed he could do all that stuff and sing at the same time.

Robbie Krieger (Photo by Henry Diltz, Courtesy of Gary Strobl at the Diltz Archive)

Robbie Krieger (Photo by Henry Diltz, Courtesy of Gary Strobl at the Diltz Archive)

“Then, what do you know. He came to Berkeley for the first time and we saw him at the Community Theater. We just got tickets. I wasn’t hooked up then. (laughs). It was a good experience. He had the buckskin jacket. I bought into the whole thing, basically. I later bought a harmonica rack holder. When I saw him live, I sort of realized at the time there were some interesting and unique tunings on stage. I thought he was pretty cool at that first concert, and then the week after that we saw Joan Baez play at Stanford University.

“I loved his Bringing It All Back Home LP. That was my favorite. It all made sense. The lyrics fit exactly what I was thinking when I was on acid. It registered, you know. ‘Wow. I’m listening to this guy.’

“My favorite song was “Mr. Tambourine Man.” I might have been in my band then called the Psychedelic Rangers. I had been playing guitar for a couple of years and started at age 15. At the Long Beach concert at first, I didn’t know what to think. Because I was expecting it to be how it was before. But then I realized this. I didn’t really get into Dylan until I saw him the next time in Long Beach in ’65. An auditorium. That’s when he first came out with the electric set. Not only that, but I was on my first acid trip. It actually was not even acid but Morning Glory seeds. I think I schlepped down from Menlo Park.

“I went by myself. I had two tickets, and I had taken these seeds with my girlfriend and she didn’t want to go. So, I went by myself and my mind was blown. I expected him to be the same as he was earlier in Berkeley, and here he comes out with an electric band and wearing a Hollywood Zoot suit. I didn’t know what to think. In Long Beach he was totally different. And that was one thing about Dylan that was always great. He always changed. I loved Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited album. I loved Michael Bloomfield’s guitar playing on that album and loved Bloomfield on the first Paul Butterfield Blues Band album.

“I never saw Bob Dylan again except when the Doors were being inducted into The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame when the ceremony was held locally in Los Angeles at the Century Plaza Hotel. We then walked backstage to get ready to go on and there was Dylan. We all hung out for a few minutes.”

Jackson Browne: “What Bob Dylan did for me, everybody and our generation it will never have to be done again. The way he opened up our thinking and our feeling and our view of the world only has to be done once. Maybe it’s done in other fields like film and painting and other art. As a people we’re constantly growing, expanding but the changes that Bob Dylan brought to rock and roll and songwriting are permanent. They’re part of us. People who are just being born into it now are being born into a world that wasn’t that way until Bob Dylan made it that way. It’s a particular skill to write something in a few words that speaks volumes. It is very difficult to say how I feel and how I think about Bob Dylan in a few words."

Howard Kaylan: “In the Turtles we cut “It Ain’t Me Babe” and met Bob one night. All of us, as singers and performers keep those great songs in the pipeline so they are not forgotten. It doesn’t have to be a great Bob Dylan song or a Tim Hardin song or even a great Leiber and Stoller song. If it’s great and forgotten you kind of feel like you are a missionary as far as getting those things to the public."

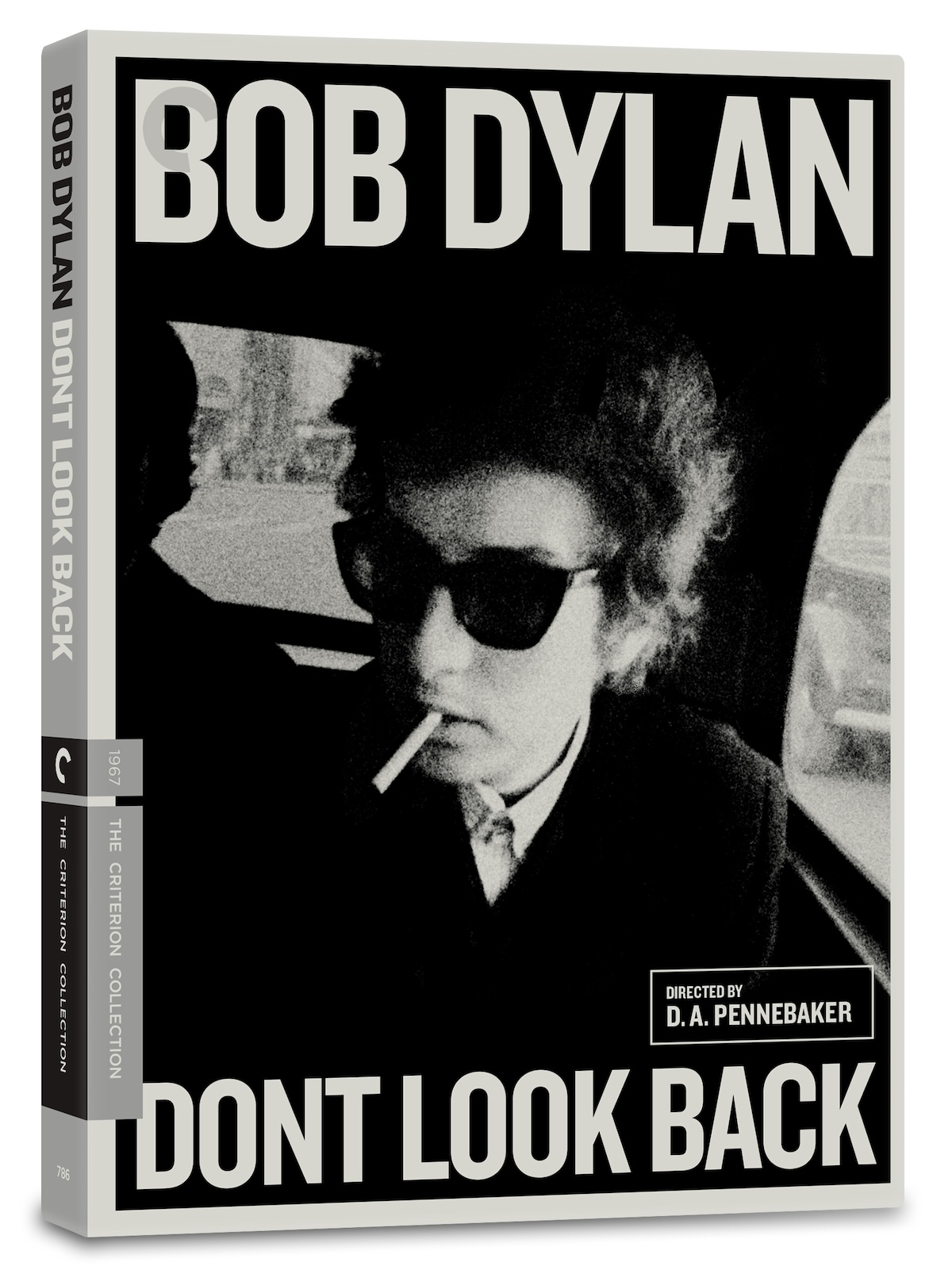

Marianne Faithfull: “I had never seen a person like Bob Dylan Never in my wildest dreams could have imagined anyone like Bob in 1965. His brain, but I was frightened. I didn’t know they were probably more scared of me. I don’t know. They were all on methedrine. He played me the album Bringing It All Back Home himself on his own. It was just amazing. And I worshipped him anyway. That was where I got very close to Allen (Ginsberg) ‘cause Allen was the only sort of person I could recognize as being somewhat like me. I spent some time with Allen and Bob during Don’t Look Back."

Brian Auger: I’d just come out of my previous band, Steampacket looking to put together something with a James Jamerson–style bassist, a Bernard Purdie feel on drums with balls-out organ solos on top. Easier said than done!

“My manager, Giorgio Gomelsky, told me that Julie Driscoll was keen to join us, and that worked for me. She brought in a different feel; she was really into Nina Simone and Aretha Franklin, and that sounded good to me as well. We were doing mostly covers—I was just beginning to write some stuff for the band and we were always open to new material. Gomelsky called us into his office and played us the acetate of “This Wheel’s on Fire.”

“Now, we knew other bands had been after Bob’s songs; Manfred Mann had just done “The Mighty Quinn,” and it was a big hit. But to be honest, I didn’t know what to make of this song. It was so minimal, almost nothing but a certain kind of atmosphere. Julie latched on to it immediately and I said, “All right, I’ll take it home and see what I can do.” At most, maybe, we can make it work as an album track . . . at most.

“Nothing came, man, nothing I did made it happen. But we’re in the studio and it all comes together. As a “jazz man,” I’m thinking, let’s get a straight-ahead groove going with a kind of walking bass line with a march feel, like something out of New Orleans. So, we laid down a basic track—piano, bass, and drums. I overdubbed the organ and then spotted a mellotron just lounging in the corner. The mellotron is a strange instrument, difficult to manage. It generates a spooky, orchestral sound from prerecorded tapes of strings . . . a floating quality very much of the period—very psychedelic. Julie’s been there the whole time and has a strong sense of how to deliver her vocal—a real soulful reading. And then our engineer, Eddy Offord, pulls out this shoebox-like device with a big dial on the front. “Hey, Brian, check this out!” It’s a prototype phasing device and we use it on the strings and organ. And wow, I’m hearing something else, man. . . This is a single. Giorgio and Julie agree and a few weeks later it’s blowing up the charts. Unbelievable, man.

“The key to the song, the hinge, is the walking bass line. It’s a jazz move in a pop song and it sounded completely different from anything else on the radio. We didn’t think about marketing or pleasing the label; our only concern was whether it was a good piece of music and did it represent us properly or not. In one day, we went from “can’t make it happen” to having a career moment. Right after, we’re playing at the Montreux Jazz Festival (sharing a bill with Aretha Franklin), the Berlin Jazz Festival, developing a really wild cult following which carries over to this day. Thank you, Bob. . .

“I was such a jazz snob. I came to appreciate Dylan as an incredible poet who used music to bring life to his words. The songs were conundrums, a real challenge to work out, and that really appealed to me. And the same is true about The Band—they were always putting the song first.

Al Stewart: “When the Byrds’ released “Mr. Tambourine Man,” [June 1965] and Dylan did “Like a Rolling Stone,” [issued July 1965] I thought, “My God!” This folk rock thing was in the back of my mind as being interesting, but I thought it had no commercial applications whatsoever, and all of a sudden it’s the biggest thing in the world. And I thought, “That’s it. I’m going to be a folk rocker because that’s the future.”

“In 1966 I saw Dylan and his group, later to be known as The Band, at the Royal Albert Hall. But I had a completely different take on it because I had been around rock bands and around sound systems. And so, I knew the technical side of it.

“The Royal Albert Hall had one of the worst P.A. systems imaginable. It was set up for political speeches. Winston Churchill made speeches there. That’s fine if the audience is sitting and listening and you’re talking into the microphone you can hear it. With an acoustic guitar you can still hear it. That’s fine. You put a rock band in the Royal Albert Hall and Dylan I think was using the house system. You couldn’t hear a word. It was totally underpowered. It was like if you had a rock band behind you and you’re singing through a transistor radio. And there was no way anybody could hear what was happening.

“So it wasn’t that I didn’t think it worked, because I had his album Bringing It All Back Home and I knew that it would work with a band, but it just didn’t work with the sound systems of the day. They just weren’t powerful enough in the UK. And that I think is the problem. [A sound board tape by a hired engineer did record a pristine 1966 UK performance]."

Elliot Mazer: “I recorded the 1969 Isle of Wight festival on the Pye mobile owned by [engineer] Bob Auger. His desk was a 16 Fader Neve -input console. I worked with Glyn Johns to record Bob Dylan and The Band at Isle of Wight.

“I had been noshing at the Carnegie Deli in New York and Bob [Dylan] came up to me and said, ‘I’m playing a show in England next week I want you to record.’ And then Albert Grossman called me a little later and asked what I wanted. Expenses and a fee. Albert was in love with The Band. He thought they were the Holy Grail.”

Jim Keltner: “I received a phone call from Bob in 1979 wanting to know if I’d like to hear his new Slow TrainComing album and maybe go on the road with him. I wasn’t really much interested in touring, but I always loved playing with Bob.

“Carl Radle, Jesse Ed Davis and I had recorded some Dylan tunes with Leon Russell as the Tulsa Tops which we did at Leon’s home studio in North Hollywood. ‘A Hard Rain Is Gonna Fall’ is my favorite.

“I was living in London, Leon called me, asking if I could come to New York to record with Dylan. We did ‘Watching the River Flow’ and ‘When I paint My Masterpiece’ on March 17th, 1971.

“A couple of years later I played with Bob on his recording of “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door’ that we did on the big sound stage at Warner Bros in Burbank for Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid. Roger McGuinn played pump organ on that session. To this day I cry when I hear Bob’s version. It’s been covered so many times but Bob’s is the only one that gets to me.

“I just had to see what he was up to. So, I went over to his studio in Santa Monica to listen to the album. I was put in a little room with a chair and some speakers. There was a box of Kleenex on the table next to me, and by the third song on Slow Train Coming I started crying practically all the way through the end of the tape.

“When it was finished, I went upstairs to a room where Bob was typing. I told him ‘Wherever you’re going, and whatever you’re going to do I want to go do it with you.’

“ I didn’t realize at the time, of course, what an effect it would have on my life.

“ I loved the rehearsals for the tour. The first one was 9/11/79.

“Every day the most incredible fresh food was delivered for lunch. Occasionally, Bob’s longtime boyhood friend, Louie Kemp, would send these big cardboard boxes of fish. Salmon, lox, and smoked fish. One big box contained a huge smoked trout. I, to this day, have never tasted anything so fantastic!

“Bob assembled a stellar cast of musicians and singers. Tim Drummond, one of my very favorite bass players, [guitarist] Fred Tackett, Spooner Oldham on organ, and one of the greatest Gospel piano players I ever heard, Terry Young.

“And the incredible singers: Clydie King, Helena Springs, Regina McCrary, Carolyn Dennis, Mona Lisa Young, Gwen Evans, Mary Elizabeth Bridges, and Madelyn Quebec.

“We ran through all kinds of different songs. Brand new ones from Slow Train and even some old classics like ‘All My Tomorrows’ by Sammy Cahn and Tommy Edwards’ ‘It’s All in the Game.’ We even played a very cool version of ‘The Ballad of High Noon’ from the movie with Gary Cooper and Grace Kelly. The idea was to get used to playing together without running the show into the ground.

“Playing Bob’s music in front of so many people on the road was a very powerful experience. I didn’t know it at the time but I eventually realized that we had all been part of one of Bob’s most important and creative periods. The last concert was 11/21/81 in Lakeland, Florida.

“I’m thankful to have played a part. Not only because of the music and the band and all of the people involved but because my life soon changed from a very destructive path I was on to working hard at keeping my family intact and to be able to continue playing music with the lights on. No longer dim and ready to go out.

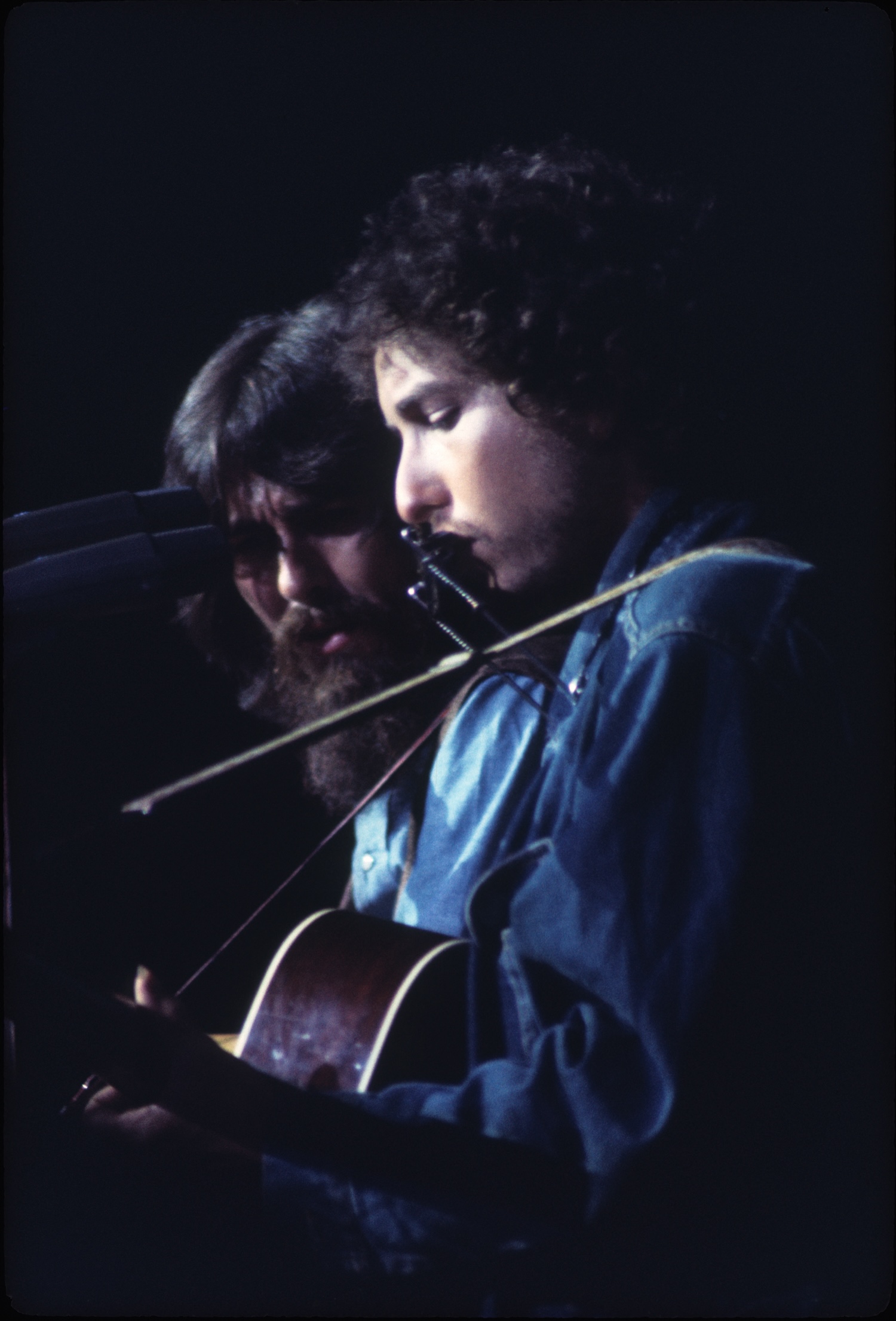

“For the Bangladesh concerts there was only one rehearsal. The rehearsal was in a basement of a hotel, or near the hotel. George was beside himself, trying to put together a set list and trying to find out if Eric (Clapton) was going to be able to make it, Where Bob (Dylan) was gonna make it. Plus, George was nervous because he hadn’t played live for a long time. He was absolutely focused and fantastic as a leader. Of course he had Leon in the band. And Leon helped with the arranging and all. I remember that everything seemed to be fine at the sound check and that I didn’t have too many concerns. When we started playing with the audience in the room it really did come alive.

“I remember loving the sound of Madison Square Garden. I heard Phil’s voice over the speakers, but never really saw him at the actual show, except during sound check. He was in the Record Plant (recording) truck.

“When George (Harrison) introduced Bob I stood backstage, and Dylan walked on. Jean jacket, kind of quiet the way Bob always is. Bob walked by me on his way to the stage. I had already recorded with him a couple of months earlier and I sort of knew him.

George Harrison and Bob Dylan on stage at The Concert For Bangladesh, August 1st, 1971 (Photo by Henry Diltz, Courtesy of Gary Strobl at the Diltz Archive)

George Harrison and Bob Dylan on stage at The Concert For Bangladesh, August 1st, 1971 (Photo by Henry Diltz, Courtesy of Gary Strobl at the Diltz Archive)

“He walks out there on the stage and puts the harp up to his mouth and starts singing and playing and chills up and down my arms. His voice and the command, it was awesome. And Leon decides to go up with his bass for ‘Just Like a Woman,’ and play with him. It was a tremendous moment. It was real dark on stage with a little light for them. Dylan was incredible. Standing in the back in the dark, it was great to see Leon have the guts to get up there with the bass and perform with him on ‘Just Like a Woman.’

“In 1992, I got asked to play with Booker T. and the MG’s which was the backup band Bob Dylan wanted for his 30th year anniversary show they later called Bob Fest. So, the first time I ever played drums with Neil Young, it was on a couple of my favorite Bob Dylan songs: “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” and “All Along The Watchtower” for his solo spot at the event. ‘Watchtower” was always one of my favorites to play. Playing it with Neil was always fun, because of the way he made it sound. Big, wide and foreboding. The song allowed him to soar, completely fly and it allows for a big beat. It has many powerful elements. Playing it with Bob was the ultimate, of course. Like Dylan’s harp solos, Neil’s guitar playing can make you feel as though you’re playing with a great jazz artist instead of whom the world thinks they are.”

Kim Fowley: “Dylan did the UCLA Folk Festival in 1963. I met him in 1965 at a party in Hollywood after one of his shows. He was pioneering everything. So of course, he would be at the forefront because that’s his job to be first.

In 1965 I sang with him in West Hollywood. I crashed the event with Bryan MacLean of Love. Dylan was in the kitchen of Ben Shapiro’s home. Shapiro was Dylan’s booking agent.

“After a quick meal, actually gobbling some food, and spiel. Danny Hutton who later co-founded Three Dog Night was with me. I went into the front room of the home, Dylan picked up an acoustic guitar and I made up some songs on the spot. Dylan said after we took over the room, ‘you’re as good as me.’ Roy Silver was my manager in 1966. And he was the original co-manager of Bob Dylan with Albert Grossman.”

Clive Davis: In June 1967 I really came to the Monterey International Pop Festival not knowing what to expect, but seeing a revolution before my eyes. I was very aware that contemporary music was changing. I was in the business side of it for a year. I was working with Andy Williams, the young Barbra Streisand and the young Bob Dylan. I was observing. I was seeing the business change. I was seeing music change."

Jonathan Taplin: When I first was given a cassette tape of The Basement Tapes by Garth Hudson in the fall of 1968, I felt like it was the American version of the Soviet Samizdat--a hand-made piece of art secretly passed from hand to hand. I think credit needs to go to Garth for recording these songs in the Big Pink basement with a rather amazing fidelity. In a sense he was following in the ‘field recording’ tradition of Alan Lomax. For both Dylan and The Band it was a way to let friends know about their new work, with none of the commercial pressures of putting out a record. And in that sense, much like the development of Be Bop during World War II when there were no recordings, a new kind of ‘Americana’ was birthed outside of any market pressures."

Harry E. Northup (actor/poet): "On October 3, 1967 Woody Guthrie died from Huntington’s chorea disease. On January 20, 1968 two Woody Guthrie Memorial Concerts were held at Carnegie Hall in New York. Dylan and his stage collaborators, the Crackers, Jack Elliot, Richie Havens, Odetta, Pete Seeger, Tom Paxton and Arlo Guthrie shared the bill [in the production written and directed by screenwriter Millard Lampell, who was a member of the Almanac Singers. Actors Will Geer and Robert Ryan served as narrators].