More Buried Treasure Emerges in the Latest Batch of Deutsche Grammophon "Original Source" Vinyl Reissues - PART 1

Emil Berliner Studios Breathe New Sonic Life into DG's Legendary Back Catalogue via these Deluxe AAA Reissues

Hector Berlioz - Symphonie Fantastique

Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Seiji Ozawa

Production and Recording Supervision: Thomas Mowrey

Recording Engineer: Hans-Peter Schweigmann

Recorded in Boston Symphony Hall, 19th February 1973

Reissue mixed by Rainer Maillard & cut by Sidney C. Meyer directly from the original analogue source at Emil Berliner Studios

180g Pressed at Optimal

Limited Edition of 3000

Music: 11 Sound: 11

If you think classical music is kind of dull, old-fashioned, lacking in thrills, staid and stodgy, here’s the work - and the record - to entirely change your mind.

The Symphonie Fantastique was revolutionary when it was written, almost 200 years ago, and in the right performance and recording (like this one) it still sounds revolutionary now.

This is the work that washed away all remnants of what came to be known as the “Classical” period in music: the age of a certain formality and emotional restraint; where head and heart, intellect and emotion, were kept in balance with each other.

This was the age of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven - although all, and especially Beethoven, exhibited tendencies of the iconoclasm that was to come. With this work, more than any other, Berlioz - the young rule-breaking Frenchman with a shock of wild hair - ushered in the swooning, overt emotionalism of the “Romantic” period, when music broke the bounds of the forms and manners that had defined the Baroque and Classical eras. Berlioz’s work may adopt the symphonic form first codified by Haydn and his successors, but he explodes it from within. Music was never the same again.

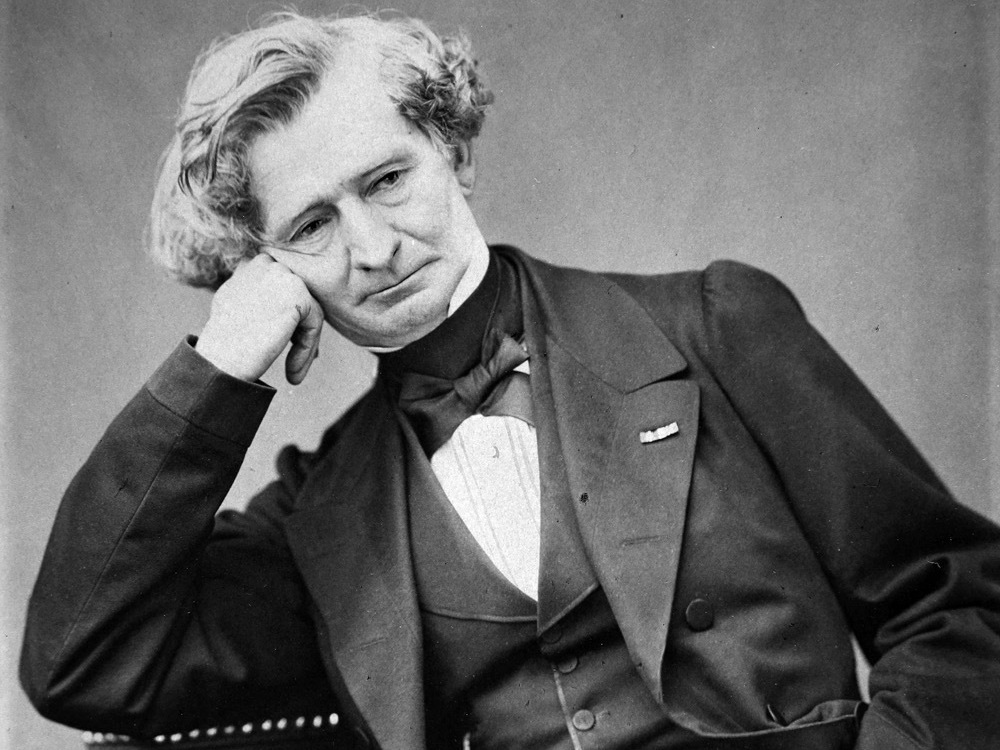

Hector Berlioz in a photo by Pierre Petit (c.1863-1864)

Hector Berlioz in a photo by Pierre Petit (c.1863-1864)

The first, and grandest, innovation of the work is that it eschews a purely musical argument per se. Within its formal procedures, this symphony also tells a story, one that is charted and illustrated at every narrative turn by the music itself with great clarity. It is the story of a musician hero who, smitten by a raging, unrequited love, imagines himself into an ever more macabre scenario, taunted by the object of his affection.

Previous symphonies were purely abstract in nature, though Haydn had often included elements that suggested to listeners extra-musical ideas like a clock, a clucking hen, or a big “surprise” (a fortissimo chord following a pianissimo introduction). Then Beethoven had gone one step further with extra-musical allusions like the so-called “Fate” motif at the opening of the 5th Symphony (“Da-da-da Daaaaaah”), or the inclusion of a chorus and soloists singing the “Ode to Joy” at the end of the 9th Symphony.

Clearly the biggest inspiration to Berlioz was Beethoven’s 6th Symphony, known as the “Pastoral” for its programmatic elements depicting life in the country: birds calling near a flowing stream, a gathering and breaking storm, peasants drinking and celebrating. The third movement of the Symphonie Fantastique is an idyllic country scene modeled on Beethoven’s Pastoral, which devolves into a far darker scenario as the musician hero murders (maybe) his beloved. It’s almost like a musical version of the pivotal scene in Antonioni’s Blow-Up, where the photographer hero slowly discovers that his photo of a quiet London park contains a dead body half hidden in the shrubbery.

The second innovation of the Symphonie Fantastique is the way in which Berlioz uses the orchestra. He throws out the rule book. He introduces several instruments new to the symphonic palette - like the harp, cor anglais (cousin to the oboe), and bells (all instruments more accustomed to be heard at the opera). He divides instrumental sections like the basses and tuned drums into multiple parts, and finds a new way to write for strings and wind which yields what we have come to know as a very “French” sound. It’s a sound that is quite different to the German one: more smooth-edged perhaps, and transparent, textured more like silk than the wood and stone of Beethoven. It’s a sound which persisted in the music of later French composers like Debussy, Ravel, Dutilleux and even Messaien.

But I get ahead of myself. The story behind this work, and the story depicted in a score of technicolor sonic originality, are in themselves fascinating and essential to fully appreciating the music.

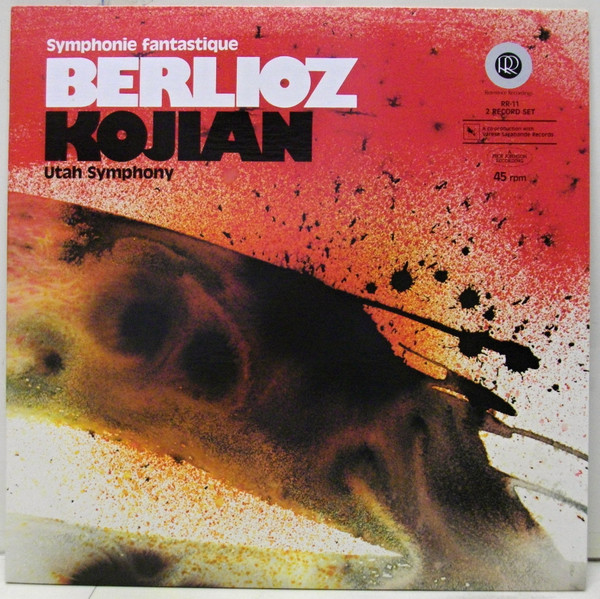

The great Berlioz scholar, Hugh Macdonald, gives this account of the genesis of the Symphonie Fantastique in an excellent sleeve note written for the 1982 Reference Recordings release of the work conducted by Varujan Kojian with the Utah Symphony Orchestra on CD and double 45rpm vinyl.

“In September 1827, Berlioz saw the Irish actress Harriet Smithson for the first time, playing Shakespeare at the Odeon Theatre, Paris… The double impression of Shakespeare and of her acting overwhelmed him, and in his memories he tells how he spent months in a delirious state, wandering in the streets, unable to bear the torment of what seemed to him a hopeless passion. There followed two more violent blows to his sensibilities: the discoveries of Goethe’s Faust, and of Beethoven’s symphonies, and the cauldron into which these impressions had been thrown was ready, in the Spring of 1830, to bring forth a large-scale work wherein Shakespeare, Goethe, Beethoven and Harriet Smithson (whose cold response had brought disillusionment and despair) are all to be found.”

Harriet Smithson as Ophelia

Harriet Smithson as Ophelia

The symphony charts the increasingly lurid passions and phantasmagoric imaginings of a musician obsessed with a woman, the unobtainable “obscure object of his desire” (to borrow from Buñuel’s film). Musically she is depicted in a melody, an idée fixe, that reappears at crucial moments throughout the symphony. Berlioz wrote a detailed scenario for the work, and any listener unfamiliar with the piece should read it ahead of listening.

The first movement, titled “Reveries-Passions”, depicts the meanderings of a mind consumed with unrequited love. The genius of Berlioz lies in the way he is able to combine the sudden shifts of tone and tempi within what is an entirely functional formal structure. Phrases ebb and flow in a perfectly realized musical “stream of consciousness”: at first uneasy, then faltering, finally passionate. I find this to be one of the most extraordinary 13 minutes in the entire symphonic literature. Performance-wise, a conductor has to find the balance between conveying the moment-to-moment palpitations with the necessary forward motion of the formal design. Over-indulgence of the musical moment, and of the pauses in particular, will make the whole thing grind to a halt; skating over those same musical gestures will short-change the passion of the work’s beating heart.

The test comes immediately. The work begins almost as if we are in mid-thought, mid-sentence, with stuttering wind chords giving us a quasi-“Once upon a Time” introduction. Violins come and go, sighing, their phrases never quite seeming complete - or leading anywhere. If a conductor mis-times any of this the performance will be still-born. Then out of nowhere the quiet forward tread of the string basses enter, and for me this is a crucial test of any recording, both in terms of performance and sound. This is the moment when you first get a sense of the sleeping giant that is Berlioz’s massive orchestra, ready to be unleashed at any moment. Those basses have to have just the right amount of ominous presence, and on this record they do. It’s an electrifying moment. You can not only hear but also feel those plucking strings, and the resonance moving around the hall.

So before I go any further into the detail of what follows, let me quickly set up the recording under consideration. Born in Japan in 1935, Seiji Ozawa had a meteoric rise as a conducting wünderkind, and was one of Leonard Bernstein and Herbert von Karajan’s most prominent pupils. His appointment as Music Director at the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1973 was a major coup; he remained there for 29 years.

Seiji Ozawa

Seiji Ozawa

The Boston Symphony Orchestra had long enjoyed the reputation of being the greatest French orchestra outside of Europe, largely due to the influence of conductors like Pierre Monteux and Charles Munch, two of its earlier music directors. With Munch the orchestra had recorded the Symphonie Fantastique on one of the greatest of the early RCA "Living Stereo"s in 1954 (more on this later).

Deutsche Grammophon had, and still has, a longer relationship with the BSO than any other American orchestra, and prior to Ozawa’s arrival had already released seminal albums conducted by Munch and William Steinberg in particular (several legendary Steinberg recordings are slated to be released in the next batch of the Original Source vinyl reissues, a tantalizing prospect).

With the arrival of Ozawa, DG embarked on a major series of recordings, including the complete orchestral music of Ravel. This recording of the Symphonie Fantastique was one of the earliest of the new partnership, and I will confess to never having heard it before dropping the needle on this reissue. In general, Ozawa’s excursions into the non-Germanic mainstream repertoire have come to be considered his most successful, along with his championing of 20th century music of all types.

In an unusual move, DG employed an American producer, Thomas Mowrey - not the usual in-house German producer - to supervise many of these Boston recordings. Mowrey was a huge supporter of the move into surround sound technology that several classical labels, primarily CBS and EMI, were espousing. So many, if not all, of the DG 1970s BSO recordings were recorded to four track tape, with two tracks dedicated to the surround channel . (You can watch Mowrey discussing his recordings here).

So when DG announced this new Original Source series of vinyl reissues, which were - for the first time ever - going to be sourced directly from the original 4-track master tapes, collectors like myself began to salivate at the thought of the BSO legacy getting this Rolls-Royce treatment.

If this Ozawa/BSO is any indication, we are in for a treat. I make no hesitation in declaring this one of the most outstanding - if not THE outstanding - release in the OSS series so far, for both its performance and the sound quality. (OK, the Kleiber Beethoven 7th and Abbado Rite of Spring are pretty great too!)

We already had an indication that the BSO recordings might be something special from the Abbado Debussy/Ravel LP released in the second batch, and reviewed by my colleague Michael Johnson here. However, I felt the occasional lack of bass detracted somewhat more than he did. No such problems with the recording under consideration here.

Returning to that key moment in the first movement of the Berlioz when the string basses enter: I feel like I am right in the hall, with the orchestra in front of me, and the bass frequencies of the hall itself (one of the great acoustical spaces in the world) are fully engaged.

And we’re off to the races.

Symphony Hall, Boston - one of the world's great acoustical spaces, built in the classic "shoebox" design

Symphony Hall, Boston - one of the world's great acoustical spaces, built in the classic "shoebox" design

Ozawa paces this first movement to perfection. If you didn’t know better, you’d swear Berlioz was tripping when he wrote this; it really is the closest a classical work gets to conveying the kind of druggy ride certain rockers and jazzers thought they had the monopoly on. But no, Berlioz’s fever dream was induced entirely by his passionate soul thwarted by unrequited love.

And it only gets more hallucinogenic from here.

In the second movement, A Ball, the elusive Beloved appears everywhere to taunt the musician hero. This is a gorgeous musical confection, all glittering harps and glistening strings and fluttering woodwind, with some rich part-writing that will have you, like Berlioz’s alter ego, swooning. Ozawa and the BSO are simply magical here.

As I mentioned earlier, the third movement takes us into the same bucolic country landscape inhabited by the slow movement of Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony - think the landscape paintings of John Constable.

The Cornfield (1826) by John Constable

The Cornfield (1826) by John Constable

Two shepherds call to each other on their respective instruments (cor anglais and oboe), and here the celebrated wind soloists of the BSO of this recording’s era take center stage: I have never heard this movement put across so vividly. You simply disappear into the sound picture.

But there is trouble lurking in paradise. The musician has another vision of the beloved, but now his paranoia and fear emerge - does she love someone else? Distant rolls of thunder on the timpani sound like ominous portents of something terrible about to happen…. As the movement draws to a close only the sound of one shepherd’s instrument calls out into the void.

Again the sound picture on this record is all-enveloping: you have a precise sense of all the instruments in the space of Symphony Hall, of where they are located, with their distinctive timbres sounding completely natural. And Ozawa finds the perfect balance between peaceful composure and looming menace.

Things do not look good in the next movement. In his despair, our musician hero has overdosed on opium, but it hasn’t killed him. Instead of dying immediately he dreams he has killed his Beloved, and is now on a March to the Scaffold. This is one of the all-time great marches in classical music, and Ozawa takes it at one hell of a lick. The orchestra is with him every step of the way, their articulation never sounding rushed, merely exceedingly precise. I can’t remember a faster tempo on a recording, and I was on the edge of my seat as I listened. The effect is thrilling, and freshens up music whose familiarity can easily provoke - if not boredom - then a certain over-familiarity.

The arrival at the guillotine brings our hapless protagonist one last vision of his Beloved before we experience one of the most deliciously graphic executions in all music: you literally hear the blade descend and our hero’s head plop down into the basket.

And things only get worse in the final movement, Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath. Yes, our dead musician is now, as Berlioz describes it, “in the midst of a frightful troop of ghosts, sorcerers, monsters of every kind, come together for his funeral. Strange noises, groans, bursts of laughter, distant cries which other cries seem to answer….”

It’s all clearly audible in Berlioz’s technicolor scoring.

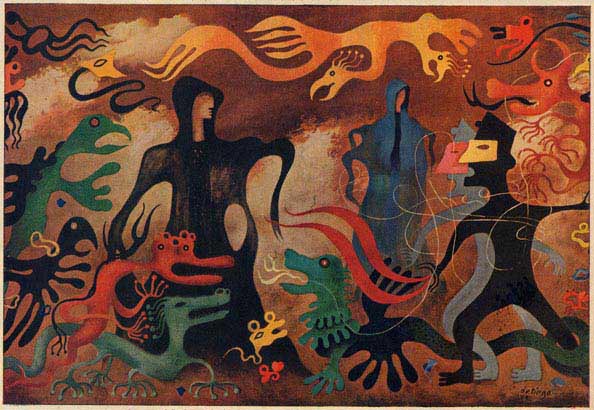

Symphonie Fantastique by Julio de Diego (1945)

Symphonie Fantastique by Julio de Diego (1945)

The melody for the Beloved appears again, but now twisted and grotesque as she rides her broomstick across the night sky.

“It is she,” Berlioz declares, “coming to join the sabbath. A roar of joy at her arrival. She takes part in the devilish orgy.”

And this is where Berlioz delivers his masterstroke. The hubbub suddenly dies away. Out of the silence peals an ominous funeral bell. This introduces the famous Dies Irae theme, used by many composers in similar deathly scenarios. Here the theme is played by bassoons, low in their register, and ophicleides, a relatively new brass instrument at the time, joined gradually by the rest of the orchestra in a masterly coup de theâtre.

A Bass Ophicleide from France in 1825, contemporary with the Symphonie Fantastique. Note the decorative horn!

A Bass Ophicleide from France in 1825, contemporary with the Symphonie Fantastique. Note the decorative horn!

This is where many recordings falter. The bell theme is usually played on tubular bells, or some variation thereof, and it often falls flat sonically, even in live performances. The bells for Ernest Ansermet, for example, on his otherwise excellent 1968 Decca recording, don’t even sound in tune (though the harmonics do - weird). Karajan, in his laudable 1975 recording, opts for what sounds like some kind of massive cathedral bell that has been electronically created or manipulated - it's actually very effective. Ozawa is fortunate to be able to forego tubular bells for a pair of special "Berlioz bells". I've never heard these used in any live performances I have attended - and it's a real sonic treat. They bring a wonderfully authentic sense of gravitas to the proceedings. The recording is so fine that when the bells ring out to announce the Dies Irae, they have a depth and presence I’ve not heard matched on other recordings. You actually hear them resonating with their physical environment, enhanced by those superb acoustics. It sends a shiver down the spine.

Original producer Thomas Mowrey had this comment to make about this brilliant moment in the recording.

"It was 50 years ago so I can’t remember for sure where we had the bells, but they were probably not backstage (as you see in the video below), but rather on the floor of Symphony Hall, where the seats had been removed.

"The entire orchestra was assembled in an oval (almost a circle, but a bit squished), with Ozawa in the center. Strings and woodwinds were on one side of the oval, in a conventional layout, and brass and percussion were on the other side, also conventionally placed. My guess is that we put the bells on the percussion side, but fairly far back from the other percussion.

"With this layout, we were able record 360 degrees of direct sound sources for the quad version (which you can hear on SACD quad release from Pentatone, apparently still available), and then when the rear tracks were folded into the front at a 1:1 ratio, that was the ideal stereo mix."

Here's that YT video which shows the bells in a more recent performance at Boston's Symphony Hall, but unlike the recording, placed offstage.

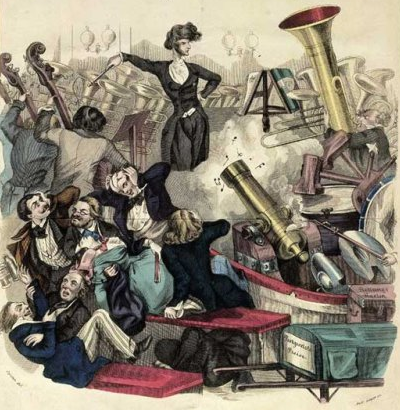

Berlioz inspired numerous cartoon/caricature representations, including this famous one by Anton Elfinger, known by his pseudonym of "Cajetan"

Berlioz inspired numerous cartoon/caricature representations, including this famous one by Anton Elfinger, known by his pseudonym of "Cajetan"

From here on in, all hell breaks loose - literally - with Berlioz throwing in a wide range of manic orchestral effects, from swirling scales in the woodwinds to the strings playing both sul ponticello (close to the bridge, creating a scratchy sound), and col legno, an effect achieved by hitting the strings with the wooden side of the bow. You can clearly hear the difference between the two techniques and their resulting sound. Unlike even the finest of previous recordings, you hear every detail of what every section of the orchestra is doing, precisely placed within the enormous soundstage, part of an organic whole. The technology necessary to capture all this simply disappears.

It’s just a splendid cacophony, and Ozawa again adopts a pretty rapid tempo to great effect. One of the joys of this Original Source pressing is that we continue to hear every detail in each section of the orchestra, even as things get very loud indeed. There’s no congestion even in the busiest, loudest sections owing to the fact that these records are cut for maximum depth and range of sonority and dynamics. One of the special thrills is hearing clear delineation between the powerful timpani and bass drums as they let loose. I mean you REALLY hear all the different timbres of what kind of sticks are hitting which parts of different drums, often all at the same time. It is one of the most exciting things I’ve ever heard on any recording. The original engineers captured the whole thing to perfection, and all I can say to Rainer Maillard and Sidney Meyer, who respectively mixed and cut this reissue, is “Bravo!” and “Thank you!”

In sum, this record represents the perfect combination of an interpretation that never puts a foot wrong, that conveys a real sense of danger, with a recording that is able to capture every nuance and the power of an orchestra working at full stretch. This is a world-class orchestra playing at the top of its considerable game; and a recording and vinyl pressing that are state-of-the-art.

Wow! Simply Wow!

Footnote: Never underestimate the power of music to sway people's hearts and souls. Harriet Smithson, the inspiration for the Symphonie Fantastique, attended a concert some two years after it was written, in 1832, at which the work was played. She was introduced to the composer, and within a year they were married.

During the Nazi occupation, the French film industry was restricted in the subject matter it could tackle. Here the French are able to celebrate one of their favorite sons in a 1942 film, with Berlioz being portrayed by the great actor Jean-Louis Barrault, most famous for his role as the mime in Marcel Carné's classic Les Enfants du Paradis (1945)

During the Nazi occupation, the French film industry was restricted in the subject matter it could tackle. Here the French are able to celebrate one of their favorite sons in a 1942 film, with Berlioz being portrayed by the great actor Jean-Louis Barrault, most famous for his role as the mime in Marcel Carné's classic Les Enfants du Paradis (1945)

Other “Audiophile” Recordings of the Symphonie Fantastique

As you can imagine, a work like this has benefitted from a fair number of fine, audiophile recordings over the years. I went through my collection and re-listened to several of the top contenders for “best recording” palm of victory.

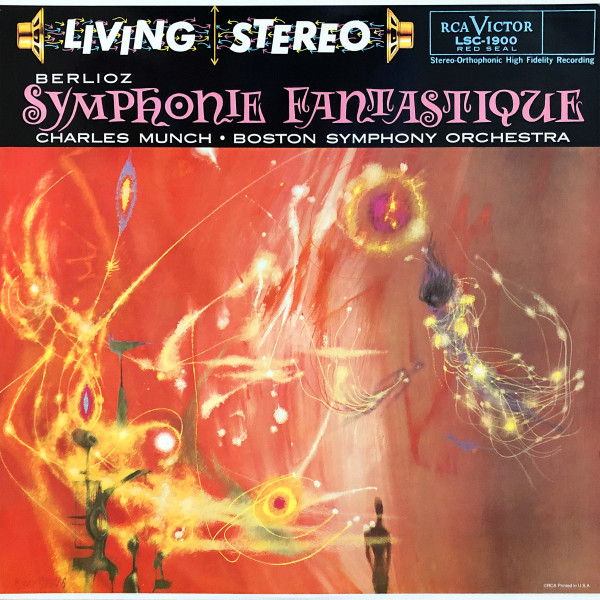

One must start with the 1954 RCA Living Stereo I mentioned earlier, conducted by Charles Munch. Originally issued in mono, the reissue by Classic Records is first class. (I am a big fan of the Classic Records Living Stereo AAA reissues, apart from the very earliest batch where the string sound in particular was a little strident; they have an energy and brilliance which I sometimes find a little lacking in the later Analogue Productions versions).

One must start with the 1954 RCA Living Stereo I mentioned earlier, conducted by Charles Munch. Originally issued in mono, the reissue by Classic Records is first class. (I am a big fan of the Classic Records Living Stereo AAA reissues, apart from the very earliest batch where the string sound in particular was a little strident; they have an energy and brilliance which I sometimes find a little lacking in the later Analogue Productions versions).

The recording puts you firmly in the front row - even on the conductor’s podium - unlike DG’s more recessed perspective. You get the classic, thrilling Living Stereo sound, remarkable for 1954. However, the excellent performance loses its way a little in the last two movements, with orchestral ensemble lacking the laser-like focus of the Ozawa rendition. Still, I would not want to be without this. I wonder why AP hasn’t reissued it……

Another classic version from the early days of stereo is the 1958 Decca with the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra conducted by the brilliant young Ataulfo Argenta. His death shortly after making this recording robbed the music world of a fine musician. One of the joys of this version is hearing the sonics of a truly French orchestra of the period (especially those telltale wind and brass timbres), all captured in vivid sound by legendary producer John Culshaw and his team (all uncredited). As with the Munch, things get a little scrappy in the last movements, highlighting again just how virtuosic the Boston players under Ozawa are. Still, I would not want to part with this, which I own in the fine Speaker’s Corner reissue.

Cover Artwork for original RCA release

Cover Artwork for original RCA release

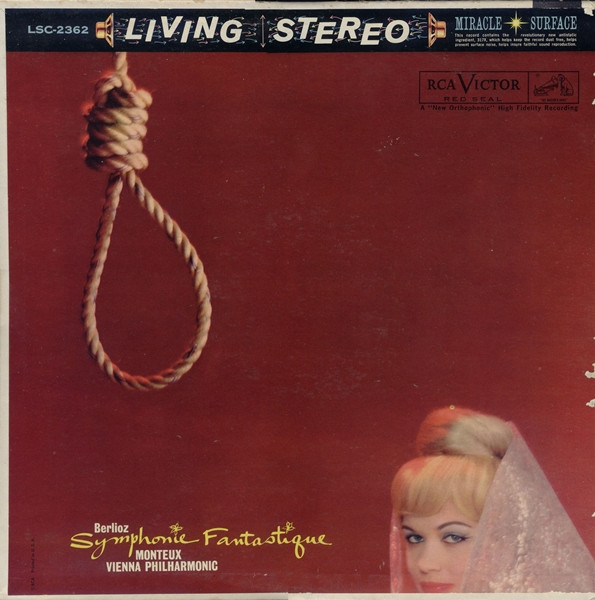

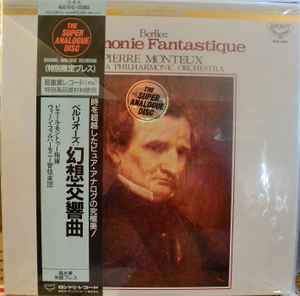

I am a huge fan of Pierre Monteux, but his 1958 RCA/Decca/London version with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra recorded in the Sofiensaal never quite takes off, despite first-class sonics (I own the superb King Super Analogue reissue).

I think part of the problem is the fact that the VPO at the time would not have been steeped in this repertoire in the same way that the BSO and PCO were. Also that very distinctive VPO sound of the period, common to all Deccas made in Vienna in the early days of stereo, isn’t such a great sonic match to the music. Alas, Monteux never seems to quite lock in to the music’s inner pulse, so there is rather more of a stop-go quality to the interpretation. But when he and the orchestra are “on”, all reservations evaporate. Still, not a primary recommendation.

I think part of the problem is the fact that the VPO at the time would not have been steeped in this repertoire in the same way that the BSO and PCO were. Also that very distinctive VPO sound of the period, common to all Deccas made in Vienna in the early days of stereo, isn’t such a great sonic match to the music. Alas, Monteux never seems to quite lock in to the music’s inner pulse, so there is rather more of a stop-go quality to the interpretation. But when he and the orchestra are “on”, all reservations evaporate. Still, not a primary recommendation.

I had never heard, nor do I own, a vinyl copy of the 1968 Decca Ansermet with his L’Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, but listening to the latest excellent CD remastering contained within Decca’s recent giant box of the Ansermet Stereo Years (review is in the works as part of a survey of Ansermet's Decca/London catalogue) has made me add this one to my list of necessary purchases. As with all the Ansermet Deccas, there is a whiff of magic about this version, and apart from the oddness of the tubular bells in the last movement I mentioned earlier, this is another winner sonically and musically.

I had never heard, nor do I own, a vinyl copy of the 1968 Decca Ansermet with his L’Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, but listening to the latest excellent CD remastering contained within Decca’s recent giant box of the Ansermet Stereo Years (review is in the works as part of a survey of Ansermet's Decca/London catalogue) has made me add this one to my list of necessary purchases. As with all the Ansermet Deccas, there is a whiff of magic about this version, and apart from the oddness of the tubular bells in the last movement I mentioned earlier, this is another winner sonically and musically.

Some of you may own the 1982 Reference Recordings 2LP (cut at 45rpm by Doug Sax and Mike Reese) version with Varujan Kojian conducting the Utah Symphony. This trumpets its audiophile credentials on the sleeve, warning listeners that the extreme dynamics may damage their systems. The sound engineering by Keith Johnson is definitely all you might imagine from this label, but I find the performance underwhelming and the balance a little too distanced for my taste, lacking the inner detail you get with the OSS Ozawa in spades.

Some of you may own the 1982 Reference Recordings 2LP (cut at 45rpm by Doug Sax and Mike Reese) version with Varujan Kojian conducting the Utah Symphony. This trumpets its audiophile credentials on the sleeve, warning listeners that the extreme dynamics may damage their systems. The sound engineering by Keith Johnson is definitely all you might imagine from this label, but I find the performance underwhelming and the balance a little too distanced for my taste, lacking the inner detail you get with the OSS Ozawa in spades.

I will finally mention the 1976 DG Karajan with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, hardly an audiophile recording, though one of his better sounding outings. I’ve always loved this version but the new OSS Ozawa has pretty much spoiled me for anything else. Karajan now sounds a little mannered and over fussy, but still, if you’re a Karajan completist, then this should be on your shelves. Otherwise, Ozawa takes home the palm. Buy it now before it sells out.

I will finally mention the 1976 DG Karajan with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, hardly an audiophile recording, though one of his better sounding outings. I’ve always loved this version but the new OSS Ozawa has pretty much spoiled me for anything else. Karajan now sounds a little mannered and over fussy, but still, if you’re a Karajan completist, then this should be on your shelves. Otherwise, Ozawa takes home the palm. Buy it now before it sells out.

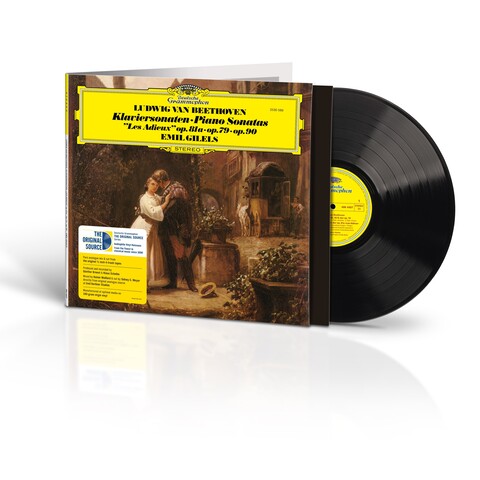

Beethoven Piano Sonatas No. 26 in E-flat major, Op. 81a, Les Adieux; No. 25 in G major, Op. 79; No. 27 in E minor, Op. 90

Emil Gilels, piano

Production and Recording Supervision: Günther Breest

Recording Engineer: Klaus Scheibe

Recorded in Berlin, Spandau, Johannestift December 16th - 22nd, 1974

Reissue mixed by Rainer Maillard & cut by Sidney C. Meyer directly from the original analogue source at Emil Berliner Studios

180g Pressed at Optimal

Limited Edition of 3000

Music: 11 Sound: 10

-1696471080.jpeg) Beethoven by August Kloeber (1818)

Beethoven by August Kloeber (1818)

The 32 piano sonatas of Beethoven, like his string quartets and symphonies, remain cornerstones of the classical music repertoire. In each of these genres, Beethoven inherited the formal procedures developed primarily by Haydn, with whom he studied as a young man, which he then proceeded to push to their limits in one masterpiece after another. The late quartets and piano sonatas, in particular, moved towards a level of abstraction which other composers only caught up with in the early 20th century. Along the way Beethoven also ushered in the more overt emotionalism of the Romantic period, most famously to be heard in the so-called Moonlight and Pathétique piano sonatas. These are the most familiar works in the cycle, tackled by every budding young pianist, testing the patience of many a long-suffering piano teacher.

By the end of the vinyl analogue era, there were many complete piano sonata cycles of great distinction competing for the claim of “benchmark recordings”. Seminal early outings by Artur Schnabel and Solomon remain essential, despite challenging sound. Moving into the LP era, touchstones included Alfred Brendel (for many his earlier cycle on Vox is preferable to his later Philips one, but Vox vinyl pressings are compromised), Claudio Arrau on Philips, Daniel Barenboim on EMI, and Wilhelm Kempff on DG (I would take his mono cycle over the later stereo one).

Emil Gilels

Emil Gilels

But it was Kempff’s label-mate Emil Gilels who for many - myself included - became the lodestar for these works in the vinyl era, even though he died before he could quite finish recording the whole cycle. The selection of somewhat less well-known sonatas on this latest Original Source reissue under consideration is, I think, the standout volume of all the Gilels Beethoven LPs. It may lack the obvious hits - like the aforementioned Moonlight and Pathétique - or the heavy hitters - like the Hammerklavier or Appassionata - but nevertheless it is the perfect entry point for anyone wanting to dip their toe into the deep waters of the Beethoven piano sonatas. Why? Because we have here three sonatas which represent three very different approaches to the form, and the contrasts tell you a lot about what Beethoven was up to in these extraordinary works, and amply demonstrate Gilels’s mastery - and why his recordings remain benchmarks in a vast catalogue.

I mentioned in my earlier review of Gilels’s DG recording of Schubert’s Trout Quintet that I heard Gilels perform in the late 1970s when I was in high school. I sat on the stage behind him, about 10ft, away, with a clear view of the keyboard. It was one of those once-in-a-lifetime experiences. The man had the most incredible stage presence, the physical embodiment of the so-called “Russian bear”. He just walked on and started playing as though it was the easiest and most inconsequential thing in the world. The coiled power of his sound was immediately apparent, as was the effortless facility with which he despatched fistfuls of chords and impossibly fast runs. (He was, after all, a product of the great Russian-Soviet school of players which also included the legends Vladimir Horowitz and Sviatoslav Richter). But with Gilels above all you were aware of an extraordinary sense of communion with both the instrument and the music: he seemed inseparable from both. The technique was so formidable and finely honed that no physical effort seemed to be required to draw out everything the music and instrument had to offer. The music just seemed to flow directly out of him, with no sense of an intermediary. The only other pianists I have felt that from in concert were Artur Rubinstein (another visitor to my school), and Murray Perahia playing and conducting Mozart piano concertos at the Aldeburgh Festival back in the late 1970s.

On that faraway evening which remains so vivid in my memory, Gilels played two Beethoven sonatas - the Waldstein and Les Adieux - the latter of which is included on this record. Both became instant favorites of mine from the cycle (frankly if I never hear the Moonlight, Pathétique or Hammerklavier again that will be just fine with me).

The history of Les Adieux is quite fascinating. It was inspired by the turbulent events of 1809, when Napoleon and the French briefly occupied Beethoven’s home city of Vienna. According to an account by one of Beethoven’s pupils, the composer took refuge in the cellar of his brother’s house, covering his ears with pillows to protect his failing hearing from the boom of the cannons. As he wrote to his publisher: “What a disturbing, wild life all around me, nothing but drums, cannons - misery of all sorts.”

Napoleon's army entering Vienna, 1805

Napoleon's army entering Vienna, 1805

Like the Pastoral Symphony, this is a programmatic work, whose three movements are titled The Farewell, Absence and The Reunion. It was dedicated to Beethoven’s student, Archduke Rudolph of Austria who, like many other members of the aristocracy, briefly fled the city and the siege.

Beethoven was well versed in the classics of Latin and Greek literature, and this sonata is full of rhythms which directly reference the verse rhythms of Virgil’s and Ovid’s epic tales of the wanderings and homecomings of Odysseus and Aeneas, rhythms which would have resonated with the well-educated audiences of Vienna. No doubt the Archduke would have been most flattered to be paired with such illustrious royal adventurers of a bygone heroic age.

The opening movement contrasts a serious adagio introduction with a more turbulent allegro, all uncertainty and unrest. Gilels perfectly captures the unsettling shifts in tone. For me the second movement is the most fascinating, for it paints the anguish of abandonment and fear of an uncertain future in uprooted harmonies that seem to wander aimlessly and without prospect of return to a home key - or home of any kind. All that is dispelled in the bright vivacity and rejoicing of the final movement celebrating the end of the siege and the return of the Archduke. No one does the ascendancy of light and hope after the darkness of despair like Beethoven, as anyone familiar with the 9th Symphony or the final scene of his opera Fidelio will attest.

For this reissue, Emil Berliner Studios wisely adopted to change the running order of the original record so that Les Adieux occupies a single side, thus preventing too long a side one. Some may miss the original chronological progression of the sonatas, but quite apart from the sonic gains of not cutting too long a side, I actually think the other two sonatas benefit from being heard next to each other - they are so strikingly contrasted. The short Sonata No.25, op. 79, may have been written in the same year as its successor, Les Adieux, but we are in a completely different world. For this is almost a throwaway work, a Jeu d’esprit (as perfectly described in the excellent liner notes by Richard Osborne reprinted for this OSS edition). It is fully in the mold of a sonata by Beethoven’s teacher, Haydn. At the risk of bringing down the wrath - or at least scepticism - of other classical music lovers, I will fully admit to holding Haydn’s piano sonatas in the highest regard, even to the extent of preferring to take Alfred Brendel’s wonderful Philips accounts of a number of these works to a desert island over any Beethoven piano sonata LP (even this one by Gilels).

What we have here is a perfectly charming, and deceptively simple, Beethovenian spin on a Haydn sonata: effervescent, witty, with a slow movement barcarolle of perfumed delight. The finale, as Osborne so perfectly describes it, “is arguably the wittiest small thing Beethoven ever wrote….. The notes tumble over one another like otters in a river…. It’s a movement which Haydn might have envied.” Yes, indeed!

And so to the final treat of this marvelous record: Sonata No. 27, op. 90. Composed five years after the previous two sonatas, we are now entering the twilight world of Beethoven’s late sonatas, a world you can spend a lifetime exploring and always find more to discover. Many have speculated as to whether Beethoven would have written such music had he not gone deaf, and it remains a valid speculation. There is something otherworldly in this music, and I still find myself a novice in appreciating its many layers and subtleties. Almost as an acknowledgment that he was entering new territory, Beethoven abandons the customary Italian movement descriptions for indications written in German. The first movement is labelled thus: Mit Lebhaftigkeit und durchaus mit Empfindung und Ausdruck (with vivacity and continuous sentiment and expressivity). It is a study in disquiet and unease. In another sign that Beethoven is making up his own rules now, there is only a second movement, not a third - and this couldn’t be more different. Nicht zu geschwind und sehr singbar vorgetragen (not too swiftly and conveyed in a singing manner) heralds music of luminous tenderness, and shows Beethoven reworking his main theme with a seemingly endless resource of invention. Its almost accidental conclusion leaves you hanging in the air, suspended in wisps of musical delight.

Gilels captures the many facets of these works to perfection. No doubt seasoned collectors will have their alternative favorite renditions of these sonatas, but I challenge anyone to produce a more perfectly rendered version of these three sonatas on a single LP.

As to the sound…. well, at the risk of repeating myself, it would be hard to come up with a less engaging piano sound than is to be found on the original DG albums of this period. The original 1975 LP was blighted, as nearly all DG piano recordings of the time were, by minimal bass, a thin mid-range, and a tinny upper register. But nevertheless we collectors still loved our Gilels, Argerich and Pollini records for the performances! So it is quite the revelation (and a relief) to hear on this Original Source reissue what sounds like a real concert grand in a real hall. Cutting Engineer Sidney C. Meyer and Mixing Engineer Rainer Maillard have again worked their magic on the original 4-track master tapes, going straight to the lathe with no intermediate mix-down and minimum (or less) electronic sorcery. Tone and dynamics are exemplary: you are sitting in the hall with Gilels (and happily I heard none of the problems my colleague Michael Johnson encountered in the Gilels/Brahms concerto set).

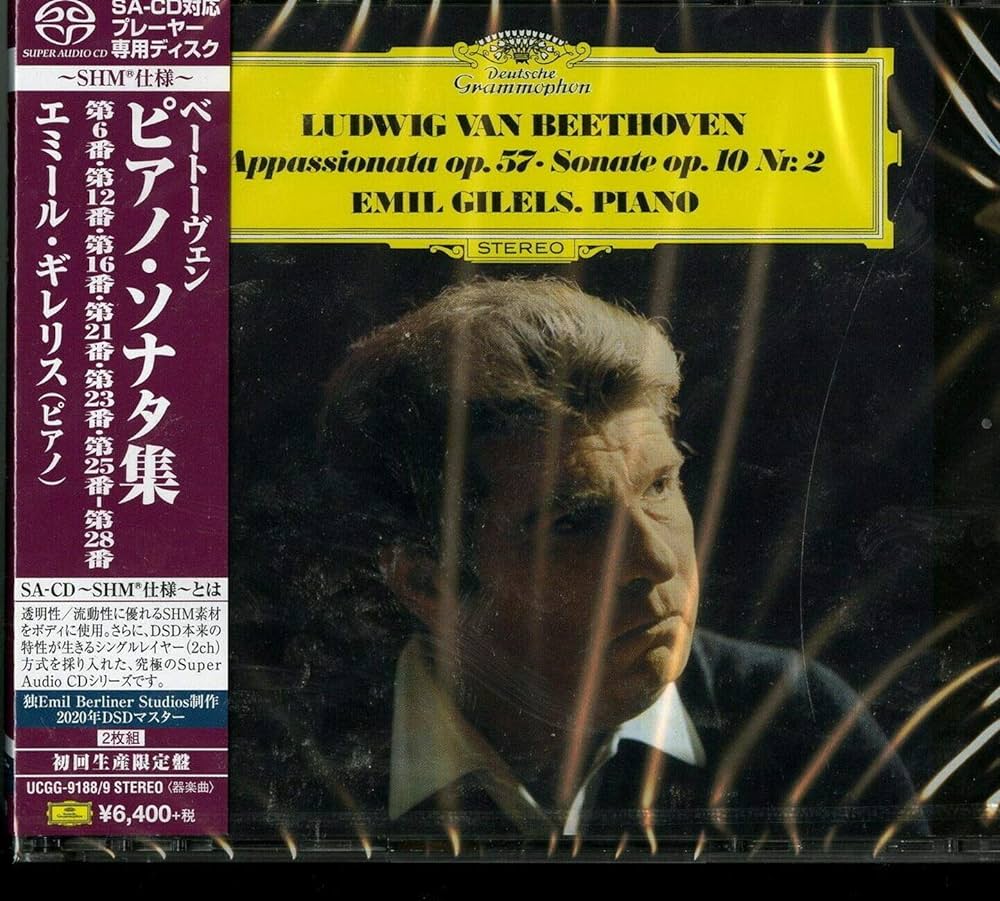

But there’s a little more to be said about the sound here. I had to hand the 2020 Emil Berliner Studios mastered single-layer, double SACD set of these works, plus other selections from the Gilels Beethoven cycle, ready to compare with this new LP, and the results were fascinating.

On the SACD the piano sound on my system was somewhat rounder, smoother than the new OS vinyl, though it also had far less of the hall acoustic in which the instrument was recorded. I would not say one version of the sound was preferable to the other per se, but I can imagine some listeners preferring the SACD sound. I found both equally involving in different ways. The SACD was a more direct, maybe more instantly beguiling sound (though no less dynamic), the LP more “real”, with more sense of immediate attack and decay, in large part because you are hearing so much more of the interaction between the piano and the space it is being played in.

On the SACD the piano sound on my system was somewhat rounder, smoother than the new OS vinyl, though it also had far less of the hall acoustic in which the instrument was recorded. I would not say one version of the sound was preferable to the other per se, but I can imagine some listeners preferring the SACD sound. I found both equally involving in different ways. The SACD was a more direct, maybe more instantly beguiling sound (though no less dynamic), the LP more “real”, with more sense of immediate attack and decay, in large part because you are hearing so much more of the interaction between the piano and the space it is being played in.

Now I know my system well enough to know that some of this was down to the different tonal balances of my digital vs. analogue front end. My Cary Audio 306 CD/SACD is a serious over-achiever, alas long discontinued. It has a warm, analog sound that never lacks for detail, with exemplary pacing and bass performance that grabs you immediately. It makes my bad-sounding CDs sound tolerable, and my good-sounding CDs and SACDs sound sensational. Therefore a finely mastered SACD like this EBS remastered Beethoven set really shines.

My vinyl front end tends towards a slightly leaner sound, especially since at the moment my usual tube phono stage is in the shop and I am using a solid state Schiit Mani 2 as its temporary replacement. Let me quickly emphasize that one need make no excuses for the performance of the almost ridiculously low-priced Schiit. Like the Cary player, it is a giant killer, and at no point have I felt I am missing out on soundstaging, dynamics, tonal richness, slam or even warmth of sound. It is so good that it has made me question my allegiance to a tube phono stage at all (my preamp and amps are all-tube). BUT - its presence in my system may have been a significant part of the reason why I was hearing such a difference between the new OSS LP and the SACD of the same works.

I fired off an email to Rainer Maillard inquiring as to the mastering provenance of the SACD. He very kindly and most generously took the time to dig into the mastering notes, and what he had to say further illuminated the differences I describe above. It was so interesting to anyone collecting these new records and/or the EBS SACDs I thought I would share what he had to say. I mean, this is the stuff we sound and music obsessives at Tracking Angle live for, n’est-ce pas!

(Words in parentheses are my additions for clarity)

“The SACD was remastered by Justus Beyer in 2020. Half of the repertoire was from 2-track sources, half 4-track. It looks like all the sonatas recorded in 1972 and 1973 were 2-track, all the sonatas recorded later were 4-track.

“For the OSS, I used a ratio for the rear channels with -3dB. This is what Klaus Scheibe (the original recording engineer) wrote with a pen on the tape box, and this is what I found best for the sound. (The photo of the tape box included with the OSS LP shows this). Justus used a little bit less rear sound for his remastering, this is what was marked in red on the original box and what seems to be the ratio for the 2-track downmix in 1974. (The downmix is what was used as a source for the mastering of the original LPs at the time of their release, thereby losing a generation in fidelity).

“(For the 2020 SACD release…..) I imagine that Justus's thought or intention was that all sonatas should sound more similar (2-track and 4-track). The old 2-track original recordings sound more direct. For a release on two SACD discs, he wanted to make it more even so that you do not hear a change in sound between sonatas recorded earlier in 2-track, and later in 4-track.

“For a stand-alone LP (like OSS), I was not forced to adjust to other (older 2-track) recordings from a cycle. That’s why I mixed it this way and what was best for this recording.

“It’s always a problem in mastering: whether to do it best for one track or do it best for a whole compilation. And to which version should we refer? And this is a challenge for a cycle recorded over many years too. Should the engineer change the sound or should he leave it as it was first done?

“To be clear: EBS always used the Original-Tapes (never the 2-track Abmischung/downmix) and we always used all the tracks on the master tapes.“Throughout our history, I know of only one example where the rear channels were not used later for a remastering: by Klaus Scheibe in the 90s, when they were replaced by an artificial reverb, because the sound of the rear channels had been corrupted.”

In conclusion: for anyone who loves the Gilels Beethoven cycle, if you do have a SACD player (and the EBS mastered discs I am talking about DO NOT have a CD layer), it is well worth searching out this double disc set. The sound is so superior to the original vinyl or any previous CD remastering.

But you must also acquire this new vinyl version of these sonatas. As I said at the top of this review, the program presented on this new OSS LP is not of the more familiar, “greatest hits” Beethoven sonatas, but is no less essential for it. In many ways it is a far richer representation and sampling of this repertoire, and as I said earlier I can think of no better single disc representation of Emil Gilels’s art in playing Beethoven. The performances are classics for a reason, and the sound is vastly improved over the original LPs and the CD reissues, and in some ways is more “live” sounding than the SACD.

As with previous OSS releases, the pressings on this and the Berlioz were dead quiet, packed in poly-lined sleeves, the physical presentation exemplary. It’s so nice to have the photos of the tape boxes etc. included, and the original liner notes.

Do not hesitate. Like the earlier DG OSS Gilels releases I predict this will sell out quickly.

Please, DG, we need represses of all OSS titles, so everyone can add these superb records to their library.

Post Scriptum:

If you are a Gilels completist - or simply a lover of great piano playing - seek out the fabulous 7-LP set put out by Devialet a few years ago of Gilels’s live recordings at the Concertgebouw made between 1975 and 1980, part of the “Lost Recordings” series that have featured many exceptional jazz performances. The set includes the three sonatas featured on the DG record. The sound is more than serviceable for a live taping of the period, albeit a little distanced from the stage, and the performances are as good as you would imagine, though surprisingly similar to the studio ones; they demonstrate just how much electricity Gilels brought with him into the studio. The set includes more Beethoven, plus fabulous Mozart, Scriabin, Prokofiev, Ravel and Chopin. It’s a limited edition, but I believe there are still copies available here on the Devialet website.

If you are a Gilels completist - or simply a lover of great piano playing - seek out the fabulous 7-LP set put out by Devialet a few years ago of Gilels’s live recordings at the Concertgebouw made between 1975 and 1980, part of the “Lost Recordings” series that have featured many exceptional jazz performances. The set includes the three sonatas featured on the DG record. The sound is more than serviceable for a live taping of the period, albeit a little distanced from the stage, and the performances are as good as you would imagine, though surprisingly similar to the studio ones; they demonstrate just how much electricity Gilels brought with him into the studio. The set includes more Beethoven, plus fabulous Mozart, Scriabin, Prokofiev, Ravel and Chopin. It’s a limited edition, but I believe there are still copies available here on the Devialet website.

In PART 2 of TA's coverage of this third batch of DG "Original Source" Series of vinyl reissues, Michael Johnson will be reviewing Rafael Kubelik's recording of Smetana's Ma Vlast with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and Mozart Piano Concertos with Friedrich Gulda and Claudio Abbado.