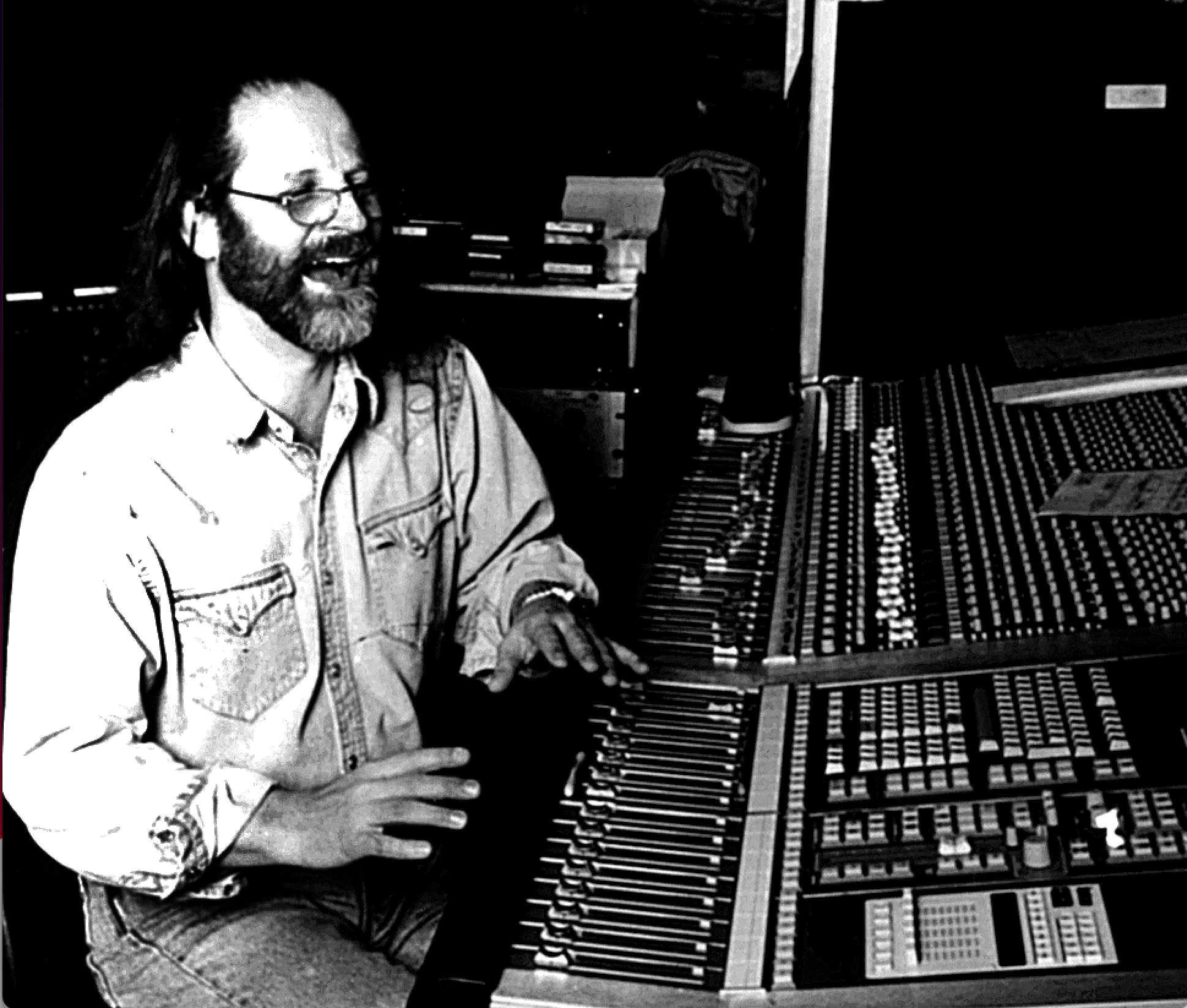

Producer/Engineer Eddie Kramer Talks 'In From The Storm' (And Other Things)

From the archives: Michael Fremer interviews Eddie Kramer about Jimi Hendrix, digital audio, and more

(This feature originally appeared in Issue 5/6, Winter 1995/96.)

“Eddie Kramer/Olympic Studios.” A magical combination. Kramer engineered Traffic’s debut album and had his hands all over the group’s second effort. Both are among the finest sounding rock records of the decade. He also is credited on The Rolling Stones’ Beggars Banquet second to Glyn Johns. Kramer also worked with The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Buddy Guy, and Kiss, among others, but his best known association of course is with Jimi Hendrix.

Kramer’s relationship with Hendrix goes back to the very first Jimi Hendrix Experience album and continued until Jimi’s death in 1970—and beyond. In the late 1960s, Kramer moved to America to help Jimi build his dream: Electric Lady Studios in New York, a place where Hendrix could work at his own pace, in his own space and on his own terms, with his most sympathetic producing partner Kramer behind the board.

Kramer engineered and mixed most of Are You Experienced?, and all of Axis: Bold As Love, Electric Ladyland and The Cry Of Love—Hendrix’s four studio albums. It was because of Kramer’s engineering skill and ingenuity (plus the contributions of other engineers) that the sound ideas floating around Hendrix’s head found their way onto recording tape.

An interview with the outspoken Eddie Kramer is something I’ve always wanted to conduct. The release of In From The Storm, Kramer’s orchestral/jazz/rock/vocal tribute to Hendrix, seemed like the ideal time to do it. I caught up to Kramer in Los Angeles (via telephone) as he was about to leave his hotel for a recording session. He gave generously of his time for this interview, and proved to be as much of a character as I’d been led to believe he was.

Fortunately, we seemed to be on the same (analog) wavelength, though, contrary to Candice Bergen’s Sprint commercials, you could not hear a pin drop during the interview. In fact, I had to call Kramer back twice, and even then the connection sucked!

Michael Fremer: In case you’re unaware, there are music lovers out there who are fans of engineers and...

Eddie Kramer: There are?

MF: Yes. There are.

EK: I guess so. Over the years, I guess people do come up to me and say, “Hey, man, you was cool, dude.”

MF: I guess that must be gratifying anyway, because to a lot of people engineers are invisible and they take for granted what they get. So I just want to say on behalf of all of our readers that we’re all big fans of your work over the years so thanks for the great sound. That said, the sound on In From The Storm is absolutely spectacular.

EK: Gee, thanks.

MF: And if you tell me it’s a digital recording, it’ll shatter my entire sonic belief system.

EK: No, it’s not. It’s all analog—well, with one exception that we’ll get into—but more about that later. My basic philosophy, I guess, is that, for the type of work that I do which is mostly in this rock genre, analog is it. It always has been and hopefully always will be. Digital just does not sound good. End of story. And I think that your magazine is well placed to put that word out.

MF: We’re trying.

EK: Yeah, it’s a tough call, but I admire you 1000% for trying this. You’re not alone and I’m not alone. I mean, it’s interesting, if you did a poll of every single engineer and producer currently working today who are using 48-track digital, who are using 32-track Mitsubishi, 20-, 48-track whatever—or any kind of digital they produce, any kind of digital recording, and ask them what do they use for their vocals? They use 50-year-old tube mics, 35-year-old tube equalizers, tube mic preamp. Just anything to make the digital sound better. Isn’t that ironic?

MF: Oh, it’s absolutely ironic. And it’s going back, I mean, there’s more recordings being done live to two-track analog in the jazz world.

EK: Do you know Walter Sear?

MF: Sear Sound? Yeah, sure.

EK: You know him at all?

MF: I haven’t met him, but I’ve seen pictures of his studio.

EK: You ought to interview him. He has a newsletter that comes out every month. You should get hold of that. He is such a character, but he’s like New York City’s kingpin for analog recordings. He’s built himself an (Ampex) 300 deck, that’s half-inch, 15ips or 30, with 300 electronics. I’ve got the same one that I’m building myself.

MF: I understand that his [Sear’s] studio has a very low ceiling and that even though he’s got great equipment, someone said to me that it’s hard to get really great sounding recordings there.

EK: Well, I don’t know about that. I think it’s a very nice room. I mean, I don’t think it’s a great rock and roll room. It’s a good jazz room. A lot of people come in and do overdubs there—all kinds of things. You should call him up anyway. And just tell him I told you to call him. And get this: he’s also got one of the old tube Studer’s, a four-track and a half-inch two-track which apparently sounds absolutely gorgeous.

MF: Yeah, I’m sure. I know someone [David Manley] who’s got one of those four-track tubed Studer’s. It was originally at Motown—that’s what they used to record on.

EK: Yeah, that’s it. Well those machines, the Ampex’s and the Studer’s from that era, you just can’t beat them. And I try in the analog world as far as I can in the project right up until the very last second.

MF: Right, then you ruin it. [laughs]

EK: Then I play. I go to a good mastering room, whether it’s Sterling or Bernie Grundman here in California, who I do think is very good, and we just pray that what comes out doesn’t sound too digital.

MF: Bernie’s cutting a lot of records now, too, which is great.

EK: Bernie’s great. This record I’m mixing right now, he’s going to cut next week.

MF: Now, is the mix down master of In From The Storm half-inch analog?

EK: Yes.

MF: Well, why can’t we get…

EK: Everything I’m doing, by the way, is Dolby SR 15ips, to give you an idea. Which leads me to the thing I wanted to tell you, the little story. There is a digital part of this, but it’s a bit convoluted. [Laughs] I used digital on the “Purple Haze” track with Bootsy Collins. That track started off as a drum track on an ADAT, which is a format I hate. Quite frankly, if you’re going to use that kind of format, I prefer the D88. I do not like the ADAT. However, having said that, Bootsy came into the studio with a drum track and a bass track which was kind of like a demo, and I said, “You know, guys, this is a great rhythmic pattern but let’s see if we can cut this thing live with Bootsy, Dennis Chambers, and the whole rhythm section.” And we tried and it just didn’t sound right and I said, “I’ll tell you what, let’s take that ADAT and transfer it to my 15ips Dolby SR 24-track. And then we overdubbed live drums and live guitar and live keyboards with Bernie Worell, and new bass parts on top of that. Then we filled that up and we put on the Buddy Miles overdub. And then I wanted to do the string arrangement. Now, of course, we were full on the 24. I made a dub of that down to DAT, took the DAT up to a friend of mine who worked for Hans Zimmer—one of his scorers who’s got this enormous all-DA-88 system, and he’s got all these incredible samples done by, what’s his name? He’s with the Czech Philharmonic, he spent like two years putting it together, we spent like $5000 for the (inaudible), you know. But anyway, we worked up at his house.

MF: You know, I have to admit my ignorance regarding the DA-88. What is that?

EK: Oh, that’s the TASCAM eight track digital machine, which I think is a way better machine than the ADAT. So we took the ADAT over to that friend’s place and transferred it to a DA-88 and now we’re in a DA-88 format. And we put all these strings on—I’m trying to think of this guy’s name who made all these samples. They’re just absolutely brilliant. He put the string parts on, and it’s like multiple layers and then we took the DA-88 back to Electric Lady and transferred it—now I ran out of tracks and I said “to hell with it, we’ll go to 48-track Sony digital.”

MF: Like the old days.

EK: Yes, so now I’ve used several different formats. I’ve got 15ips analog 24-track, ADAT, DA-88, and now Sony 48-track dig, and we still ran out of tracks. So I had to lock up another 15ips slave because then I had to go to California to do some vocals on another song on the Sass Jordan track. She’s a great rock singer on MCA or a subsidiary of MCA.

MF: Yeah, it was a great track.

EK: So, anyway, I had to go and do a new vocal and I said, “you know, this track that we cut with Bootsy needs a great rock solo.” Cause I’d gotten to a point where the guy who was doing the solos was good, but he wasn’t a rock guy. You know, he’s more of a blues type guy. So I said “(let me get) Steve Lukather,” because I had just worked with him and the track he did, “Have You Ever Been (To Electric Ladyland),” was beautiful. So I walked into Capitol Studios at 9:00 AM one morning. He was there precisely on time. By 9:15 we had a sound. By 9:30 the thing was in the can. That’s how efficient and how great he was.

MF: Wow. That’s LA studio guys, right? I mean they know how to do that kind of stuff.

EK: Yeah, but I mean Steve is fabulous. He’s just into the spirit of the whole Hendrix vibe. So now I have a 24-track slave tape machine, you know, locked up with a 48-track Sony Dig! So that one track represented every format you could throw at it. But it was fine because you see the sounds were created analog first, and I used the 48-track Sony Dig as a storage medium. Anyway, that’s a convoluted story but it gives you the idea that I do use digital for its storage capabilities. On one other track, actually, two other tracks, I used 48-track Dig only because the artists were mainly Sting and when I recorded Sting at his house with John McLaughlin, he had a 48-track Sony.

MF: But that track (“The Wind Cries Mary”) sounds great!

EK: It does sound very good.

MF: In fact that’s the best Sting recording…

EK: But think about how I recorded it. All the microphones are tubes, all tube microphones, tube mic preamps and stuff like that which I threw in and two equalizers to make, you know, warm it up. The Dig sounds good, but that room that we recorded in is just a fabulous sounding room with great acoustics.

MF: Because Sting’s personal recordings, his solo albums, are unlistenable. I mean they’re unlistenable. They’re so bright and edgy and sibilent.

EK: Well, because he doesn’t use stuff that I use.

MF: Oh, okay. He (and his engineer) doesn’t have your (recording) chops either, I’m sure.

EK: Well, he’s okay. I mean he just has a different vibe about the stuff he does which is—look, I can’t make a comment whether his stuff is unlistenable or not. I just love working with him, and that room does sound very good if you treat it right.

MF: Now, if it’s a half-inch analog, 15ips Dolby SR master tape of this project, why can’t we get someone to press it up on, I think Bernie Grundman…

EK: Very good idea. There is a vinyl picture disc.

MF: Yeah, but picture discs usually don’t sound very good.

EK: Probably sounds like crap. I haven’t even bothered to…

MF: It’s also easier to go out and buy heroin than it is to find that record, I mean that’s, you know, it’s very difficult to find limited edition records like that around. The record companies don’t even know it’s been released. I mean, you can’t imagine. Someone like me, who’s into this stuff has to run around to try and find out even if it exists. It’s impossible.

EK: Well, based upon what I’ve seen in your magazine, I mean, how many could they press (of a high quality vinyl version of In From The Storm)? 1000? 1500? 2000?

MF: They could do 2000-3000.

EK: On high grade vinyl?

MF: You know, Bernie could cut it and then RTI could press it on 180g vinyl, and it would be sold through the usual audiophile channels and you’d sell 2-3k copies. It would be the publicity you’d get from it would make it worth doing.

(The conversation gets into the logistics of reissuing the album on high quality vinyl and what it would take to do it and through whom, and who should be contacted at the label, etc.)

MF: Let’s get back to this project cause this is so cool. So, first of all. It's been 25 years since Jimi’s death. How long have you been planning something like this?

EK: I’ve had it in the back of my mind for many years. Steve Vining [at RCA Victor] asked me if I would be interested in doing symphonic music for Jimi Hendrix. I said, [kidding] “hey dude. No, I'm not.” I said, obviously, I’d be honored, but I said “if we’re going to do it, I don’t want to do it the way you did the Stones [symphonic] record, or the Yes [symphonic] record which I didn’t like ‘cause it was missing one very key item and that was the rhythm section. If you do this, let’s do it with the best rhythm section that money can buy,” and that’s how this whole thing started. And it took me a long time to put it together, about 11 months, for various reasons: one because I had to spend about a good six to eight weeks researching all the material, finding the right songs that would translate to an orchestral format. Some of the songs just wouldn’t translate because of the chord sequences, etc, so I picked the ones that had the strongest melody and the strongest chord sequences that would allow us to translate into the classical domain.

MF: How did you match the performers with the songs?

EK: Well, we had done the Stone Free [Hendrix tribute] record (Reprise 9 45438) which did very well, so we sort of took our ideas from that and just expanded upon it. One thing we didn’t do on Stone Free was the real jazz center, core guys, the guys who I wanted on like Tony Williams and Stanley Clarke. We didn’t get a chance to work with them.

MF: I think this is a much more successful project, frankly.

EK: Yeah, I think in some ways it is because Tony had played with Jimi and once he came on board it was easy to get Stanley and it was easy to get Carlos [Santana]. It was easier to get a lot of these guys once they knew that Tony and Stanley were on, it was just a snap. And so the jazz area was covered. However, Tony wanted to make sure that he was playing with as many rock guys as he could, because he was very cool about this whole thing. He didn’t want to play like the normal Tony Williams kind of free form jazz thing; he wanted to play rock and jazz fusion which I thought was terrific because he was very respectful of the music and very respectful of what Mitch had played originally.

MF: Right. Well that’s where Jimi seemed to be heading anyway.

EK: I think so. I think had he lived, you know, this goes back to the question you asked before, you know, how come, it’s been 25 years? Because the idea had been germinating in the back of my mind, like I said and, you know, Hendrix had said in print many times that he loved the idea of his music being played by a large orchestral band of professional musicians. Once I was up at his hotel delivering a tape and I looked at the record player and there was a stack of classical albums on it. “Hey, Jimi, what’s with the classical music?” He said, “Hey, man, I get a lot of my inspiration from this stuff.” I come from a classical background and was trained as a classical pianist, so that was a turn on for me. I said “Geez, I had no idea, Jimi. I’m very impressed.”

MF: What was his demeanor when he wasn’t “on”? Because when you see movies and videos of him, you see he’s chewing gum and he’s always, like, on. Was he like that?

EK: How do you mean?

MF: Just his overall energy vibe. Was he always chewing gum and on and?

EK: Oh, yeah. Jimi was an up guy. I mean, you know, he was very sharp, very together. Certainly when he was working with me in the studio he was.

MF: Are you concerned at all about the reaction of the Hendrix fans to the concept of this record and the orchestrations?

EK: No, not really. I mean, you know, look anytime you approach a Hendrix project, you’re going to get nailed by somebody. You can’t please all people all the time. You just can’t. I did the best I could with what I thought was an approach that would approximate what Jimi would have wanted. I always try to put Jimi’s view in my mind as to how he would have approached something and you know, obviously had he lived, of course, it would be different. But this is my interpretation of what I think Jimi would have liked to have done. I mean I worked really hard to get the arrangements to sound like his guitar. I took his music and transposed it into an orchestra.

MF: I thought it worked great. I was hesitant at first when it showed up, but as soon as I played it—I think Paul Rodgers’ “Bold As Love”—that track is stupendous.

EK: A nice track, isn’t it? I’m working with Paul right now as a matter of fact. The project I’m working on right now is an instrumental album actually, with this guitar player who’s from Japan, but he’s actually American. His name is Tim Donaghue and he plays a fretless guitar that he made himself and we thought, well, you know, it’s going to be tough to get him launched here in America so I said to him, “If you had your choice of singers, who would you pick?” He said Paul Rogers. I called Paul and he listened to the track and he said, “yeah, I could write for him.” He actually wrote or co-wrote four of the songs.

MF: He’s one of my favorite singers. I met him in a hotel room when he was with Bad Company and Chas Chandler was managing them and my hair was probably about three feet long, up high, in an Afro, and he said to me, “can I have your hair”? And I said, “give me your voice, you can have my hair.” Anyway, how did you come to use Toot Thielemans on “Little Wing”?

EK: Well that track is purely an instrumental track and I wanted it to be a track where there were no sort of vocals at all. Originally I was going to put soprano sax on there, but because of scheduling and whatever, I couldn’t get the guys I wanted.

MF: Who did you want?

EK: The guy from the Leno show who’s now no longer there. Branford Marsalis.

MF: Another audiophile and analog fan.

EK: Oh, good. I couldn’t get him because he was doing his tour or whatever. So, I said, “well, what’s close to that?” And I came up with the idea of a harmonica and I thought, geez, you know, there are only two great harmonica players, Larry Adler and Toots Thielemans. Toots is more of a jazz kind of a guy, and I went for Toots and he agreed to do it. What a sweet man. He’s 82 years old and still kicking dust.

MF: Well, listen, as good as some of the singing is on this project, what it really points out to me is how great a singer Hendrix was.

EK: Exactly! He was the master interpreter of his own thoughts.

MF: Yeah, but more than just that. There’s something so compelling, I played all the records the other couple of days and there’s something so moving about his singing. He never thought he was a great singer, though, huh?

EK: No, he thought he had the worst voice in the world. He made me construct these three-sided booths, you know, pointing away from the controls so nobody could see him when he sang. Very shy about his voice. He thought he had the worst voice in the world.

MF: Well, people sometimes think that when they hear their own voices, but obviously that wasn’t the case.

EK: He was just the master interpreter. I mean he could interpret a song with such passion and feeling and, of course, you know, when the artist writes a song and sings it you get a better shot. I always feel that and, I mean, he was a great stylist. I don’t know about vocally from a technical point of view, but certainly from a stylistic point of view, the guy was incredible.

MF: Well, the humor. He had a humor that I think…

EK: Sly humor, very sly.

MF: Did you hear the Gil Evans Orchestra Plays The Music Of Jimi Hendrix record?

EK: Yeah, I thought it was okay. It didn’t really kill me.

MF: Now, who was the London Metropolitan Orchestra [the orchestra used on In From The Storm]? Is that a pick up orchestra?

EK: It’s a new orchestra combination. Yes, you could say pick up. They did the new [Jimmy Page/Robert Plant] album, the one that has all the Moroccan and Egyptian musicians on it. They feature the top guys from the London Philharmonic and…

MF: Did they have fun doing this?

EK: Oh, they really got into it!

MF: How old are most of them?

EK: A lot of young players. A lot of women, young kids, in fact, one of the cello players is an old friend of mine from way back when. In their 20s and 30s and 40s and some of the older guys in their 60s.

MF: How difficult was it to get the orchestra to play behind the rock tracks? Is that how you did it? You brought the tapes…

EK: Oh yeah, there’s no way you could do this without cutting the tracks first. That was the plan. All the tracks had to be completed before I brought the tapes to England and then we overdubbed.

MF: How much work did it take to do it? Were they having difficulty?

EK: We were doing two charts every three and a half, four hours. It was amazing how fast they were.

MF: And it works great. They put a lot of "oomph" behind it.

EK: Well, you had to wind them up a bit! We had to tell them to keep digging, and digging and digging in ‘cause they’re not used to playing with that kind of intensity. But once you show them a couple of times, then they get it.

MF: And then the mix was really great, too.

EK: Yeah, I mixed at Electric Lady. It's a tough job, you know, to sort of combine an orchestra and a rock band. It’s very hard because sometimes some people say, “oh, well, it’s too much orchestra.” Some people say it’s not enough. So, like I said, you can never please everybody all the time. I just tried to blend it as carefully as I could so that all the music stood out.

MF: It's a really wonderful mix. Let me ask you this question. Alan Douglas: hero or villain?

EK: No comment. What do you think?

MF: Well, erasing and overdubbing new rhythm tracks is…

EK: Is villainous. You can quote me on that.

MF: Yeah, it’s villainous and inexcusable. How was that allowed to happen?

EK: Because at that point he was in charge of the Hendrix estate. Now, thank God, he’s no longer. All the tapes belong to the family now. They have everything.

MF: That’s been settled?

EK: Oh, yeah, they’ve been working on it for months now.

MF: Now, what’s happening with the catalog as far as releases go, do you know?

EK: From what I can understand, I think they’re in the midst of putting a new deal together. From what I gather, the masters, hopefully the original masters—you know, a lot of these reissues that have come out in the last 10, 15, 20 years have not used the original masters. And hopefully the original masters will be found and the stuff will come out properly. I’m definitely going to recommend they do vinyl.

MF: Oh, great. All analog. You know, the Beatles catalog is coming out on vinyl again, digitally remastered and I called Capitol and said, “well, don’t bother. Don’t waste your time. It’s stupid.”

EK: Yeah. Well, what can I tell you? You know, this whole digital thing is a big question mark in my mind. It’s tough.

MF: Will you supervise the vinyl?

EK: If they ask me, I would love to do it.

MF: I’d love to do a story on that. So, now, you don’t know where all the master tapes are. Are any of them in England?

EK: Well, it seems that quite a few of them have gone missing. But they’re in the process of trying to find them. And I can assure you that there’s stuff that will be issued that has never seen the light of day before because a lot of people never wanted to deal with Douglas.

MF: Now, is there an original Track Records mono mix of Are You Experienced that you made?

EK: No, only stereo.

MF: So you never did a mono mix?

EK: I don’t think so. I think it was all stereo.

MF: Do you remember what was shipped to Warner Brothers for the American issue of Are You Experienced?

EK: No, but you can ask John McDermott. Have you read our two books?

MF: Oh, yeah. They’re wonderful. The sessionography. The sessionography book to me has more emotion in it than the other book because…

EK: Well, the other book was more of the business stuff and what really happened behind the scenes which was important to establish because you get a really good picture of what it was like from the inside. I mean, that was the intention of that book. This one is more about what he did in the studio and how he created.

MF: But emotionally, you can see him finding his compass, losing his rudder. I mean you can just—there are parts…

EK: Yeah, you can call John up. He’s a fund of knowledge, and I’m not sure how much he’s going to give you, but I’m sure he’ll give you a lot of good stuff.

MF: Regarding Axis, do you remember what Warner Brothers used to master that?

EK: Ask John, he knows every tape there’s ever been.

MF: I’ll ask you one last question in this regard, because maybe you have something. Electric Ladyland, when that tape was shipped to Warner Brothers, the original came from your studio and then apparently…

EK: You mean from the Record Plant?

MF: Right, and Jimi was apparently disappointed because they did not leave all the phasing stuff that you put in there.

EK: Well you see, in those days, mastering was not the art that it is today. Those assholes [at Columbia Studios, where it was mastered] didn’t know their butts from their front face, and if you presented them with a tape that was slightly unusual, they had no clue how to deal with it. So, of course, you know, stuff that was out of phase or sounded weird was just treated with disrespect. God only knows what they would do.

MF: Because I have a British Track pressing which certainly couldn’t be from the master tape if the master tape went to Warner Brothers, so it must have made a dub, but that original British pressing has all the out-of-phase stuff on it. If you sit and listen to it, it sounds like a Dolby surround mix.

EK: Oh, yeah, it’s good. You see, in those days, the guys at Columbia were all union—they had no clue what was going on. Nobody was supervising the mastering. So that’s the reason it sounded like that.

MF: Yep. It’s too bad, the American pressing is just lacking in all that spatiality that’s in there. Are any of the CD mastering jobs of any of these first four albums of any use to you?

EK: I don’t think so, quite frankly.

MF: Have you heard the HDCD The Ultimate Experience?

EK: No. I haven’t heard that.

MF: I haven’t either [I have since]. So, one of my questions was, what are the chances of all this coming out on vinyl? If we could do that, it would be fantastic.

EK: Well, if I have anything to do with it, yes.

MF: Good. There are enough people out there wanting it to make it worth doing.

EK: It would be a big splash if it came out on vinyl with the proper covers. The sound of the vinyl just kills.

MF: The same with the Stones albums. I mean, the Stones album that came out on CD in this country on ABKCO are so horrendous, so terrible, and I sent them a long letter and said, “It deserves to be redone on CD, and on analog vinyl with the original Decca running order” and they said, “Well, we’ll think about it.” So, that would be nice. Now you were once quoted as saying “digital sucks.” Were there any repercussions from that?

EK: Don’t care. I’m right.

MF: Well, of course, you’re right. I know.

EK: So, I don’t care who hears it, who sees it. I mean, my opinion is that it does and you can’t argue with me that it doesn’t. I mean, nobody can tell me if I put a vinyl pressing against a CD and you “A/B” the two, the vinyl won’t blow it away. You and I, and most of the guys in the industry, know this. Digital was fostered upon the American public. It’s phony. It’s horrible. It’s a storage medium at best and that’s as far as it will ever go. Maybe if you get up to 100kHz sampling rate, maybe, maybe then it will sound better.

MF: Did you hear about the new DVD that's coming out? They’re claiming we’re going to have 20- to 24bit, 96kHz sampled digital.

EK: I don’t care.

MF: That’s still not going to do it?

EK: I don’t think it’s enough.

MF: Robert Fine, the engineer from Mercury, got in front of the Audio Engineering Society in the 60s and he said “digital’s going to come. I know it. Please don’t accept it until it’s at least 100kHz sampling.”

EK: And he was right.

MF: And they wouldn’t listen to him.

EK: Bob Fine, by osmosis, had absorbed—I met him many years ago, he and my boss at the time Bob Auger, his counterpart in England. They taught me how to record. When I worked at Pye Studios in the early 60s, it was an all-American-type studio. It had Pultec [tube equalizers], Ampex tape machines, Scully lathes, Westrex compressors, the whole bit. We were learning the American way of recording and Bob Fine and Bob Auger used to exchange tapes and notes all the time—techniques. Bob Auger used to do the Westminster recordings live to three-track which I got to help him on. And, of course, Bob Fine was doing all the 35mm and three-track stuff for the Mercury Living Presence series. And I used to go out on the road with Bob Auger and do these three-track recordings with three U47’s, straight to tape. That’s where I learned a lot of my techniques.

MF: Are you passing this on to some of the youngsters coming up?

EK: I’m trying. I do lectures and stuff like that and I hope to pass a whole bunch more. I have a videotape called Adventures In Modern Recording. It’s a three-and-a-half hour video tape all about how to make a great record in your home.

MF: Can you stomach going to AES meetings?

EK: Not really, that doesn’t really attract me.

MF: Okay. Have you seen that new cartoon book about Jimi Hendrix called Voodoo Child?

EK: Don’t touch it. It’s an Alan Douglas thing. It’s going to be pulled anyway. There’s a big lawsuit about that.

MF: Because of the CD?

EK: It’s illegal. I’ve got to run now. I’m late.

MF: Thank you for your time, it was great.