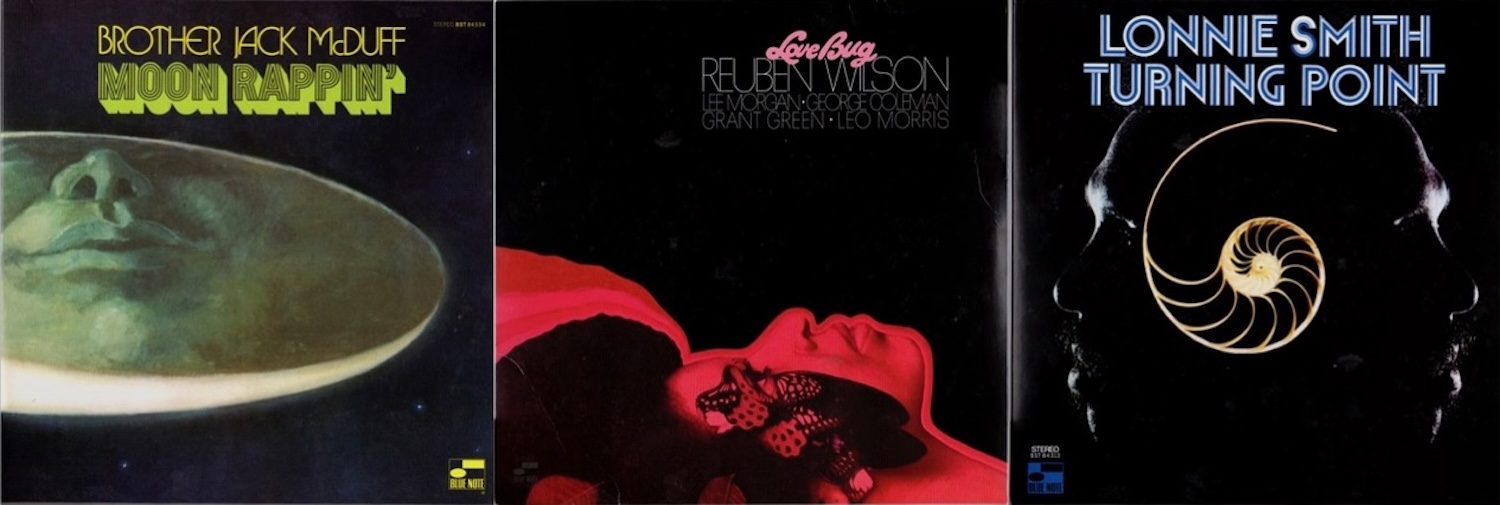

Catching Up With The Blue Note Classic Vinyl Series

Three Funky Jazz/R&B Organ Records from 1969

The Blue Note Classic Vinyl series has issued nearly 100 records since its inception in 2020 and put back in print many of the long acknowledged classic Miles, Monk, Rollins, Mobley, Morgan, Shorter, and Hancock LPs from the label’s incredible bop/hard bop catalog. The series has also released a substantial selection of funky jazz/R&B organ records from Blue Note’s late period, which have been ignored by fans of “Blue Note jazz” but revered and considered equally classic by a younger generation of collectors coming from DJ culture, hip hop, and dance music.

Old school hard bop fans of the RVG and Plastylite “P” in the run-outs variety usually date the beginning of the end of Blue Note to 1965 when Liberty Records bought the label and its final demise to July 1967 when co-founder and main creative director, Alfred Lion retired. Business partner Francis Wolff and A&R man Duke Pearson continued recording established Blue Note artists playing jazz for several more years, but, as Lion had undoubtedly foreseen, no hyphen, no compromise jazz was no longer commercially profitable in the late 1960s, for even a low budget, independent like Blue Note and certainly not for a major label like Liberty Records.

Jazz organ record sales, mainly to Black people, which had kept Blue Note afloat since the emergence of Jimmy Smith and funded the many poor-selling Lion favorites like Herbie Nichols, Tina Brooks, Sonny Clark, Andrew Hill, Sam Rivers, etc., had dropped precipitously. The jazz audience was aging, and a generation of young Black people had grown up listening to R&B and soul, not jazz.

Black culture was changing, and jazz had to change as well. Blue Note, in mid-1968, signed the funky, R&B, pop/rock-influenced, post Jimmy Smith, organists Reuben Wilson and Lonnie Smith, and released albums by them. In 1969, Wolff and Pearson fully committed the label to the new funk/jazz style. Wilson, Smith, the recently signed veteran jazz organ star Jack McDuff, and the alto saxophonist Lou Donaldson, with organist Charles Earland, all recorded two albums in the style. The byword was “funk.” Albums entitled, Everything I Play Is Funky by Donaldson and Electric Funk by organist Jimmy McGriff were recorded within a few weeks of each other in August/September 1969 at the same time Miles Davis was recording Bitches Brew. Miles wasn’t the only one searching for “New Directions in Music.”

The Classic Vinyl Series has reissued three seminal, widely sampled jazz/funk organ records from 1969, which marked the final flowering of Blue Note as a jazz label. In 1971, Wolff died, and Duke Pearson left the company. Blue Note began using outside producers and turned toward a fusion of pop and R&B with jazz flavoring. Donald Byrd’s heavily R&B/funk/disco influenced Black Byrd album was a huge commercial success in 1972 and served to point the direction in which Blue Note, while recording artists like Bobbi Humphries, Ronnie Laws, Marlena Shaw, Noel Pointer, and Earl Klugh, would move in for the rest of the 70s. Blue Note had lost its identity as a “jazz label.”

Organist Lonnie Smith (1942-2021), not to be confused with his contemporary, the keyboardist Lonnie Liston Smith, recorded Turning Point in January 1969. It was his second Blue Note album and featured the all-star horn lineup of Lee Morgan (trumpet,) Julian Priester (trombone), and Bennie Maupin (tenor sax), along with organ group guitar mainstay Melvin Sparks and the legendary jazz/funk drummer Idris Muhammad, then known as Leo Morris.

Smith, a very talented player with serious jazz chops, was an innovator who updated the Jimmy Smith style by using James Brown/funk rhythms and playing a repertoire relying heavily on soul and pop covers. Turning Point features two Smith blues originals, two covers of soul hits, and a version of “Eleanor Rigby.”

The album begins with Idris Muhammad laying down a mile wide, boogaloo beat on Don Covay’s “See Saw”, a recent hit for Aretha Franklin. Muhammad’s playing throughout the album is incredibly innovative. No one before him had played, with such exceptional technique, a style based so heavily on R&B, New Orleans, and African rhythms to create grooves of such power in a jazz context.

Smith’s tune “Slow High” is a medium blues that features a Maupin tenor solo that ventures into Trane/Joe Henderson territory and well beyond the meat and potatoes sax soloing expected on an organ group blues. Smith plays some deep, down home, but hip blues. The great Lee Morgan here, as throughout the album, seems bored or playing down to the music.

“People Sure Act Funny,” a hit in 1968 for soul artist Arthur Conley, has an outrageously fat back beat by Muhammad, which inspires Smith to lay back in the pocket and play some grooving, complex rhythms against it. Melvin Sparks changes the mood by playing a beautiful, melodic guitar solo that shows he has been listening to Grant Green.

“Eleanor Rigby” is not a tune that one would expect to find on a funky jazz organ record, but Smith’s arrangement works surprisingly well. The solos are not on McCartney’s chords but on an E minor scale over a vamp. Maupin’s is abstract and sounds like Wayne Shorter with Miles. Morgan is uninspired, but Smith’s solo is a hard swinging masterpiece that builds to an intense climax over Sparks’ rock-ish rhythm guitar and Muhammad’s tight/loose groove variations over a New Orleans parade bass drum beat.

“Turning Point,” another blues based Smith original starts with him quoting “All Blues.” The chord changes seem to inspire the horns. Julian Priester plays a fine boppish trombone solo. Maupin is creative and a bit “out”. Morgan, sounding far from his best, plays some of his favorite licks. Once again, over amazing drumming, this time jazz drumming, by Muhammad, Smith shows what a talented player he was, burning through some sophisticated variations on the chord changes while swinging as hard as Jimmy Smith.

The music on Turning Point straddles jazz and funk and should appeal to fans of both genres. There are plenty of amazing funk grooves, courtesy of Muhammad, and some superb jazz soloing by Smith. It’s a classic jazz/funk album and is recommended.

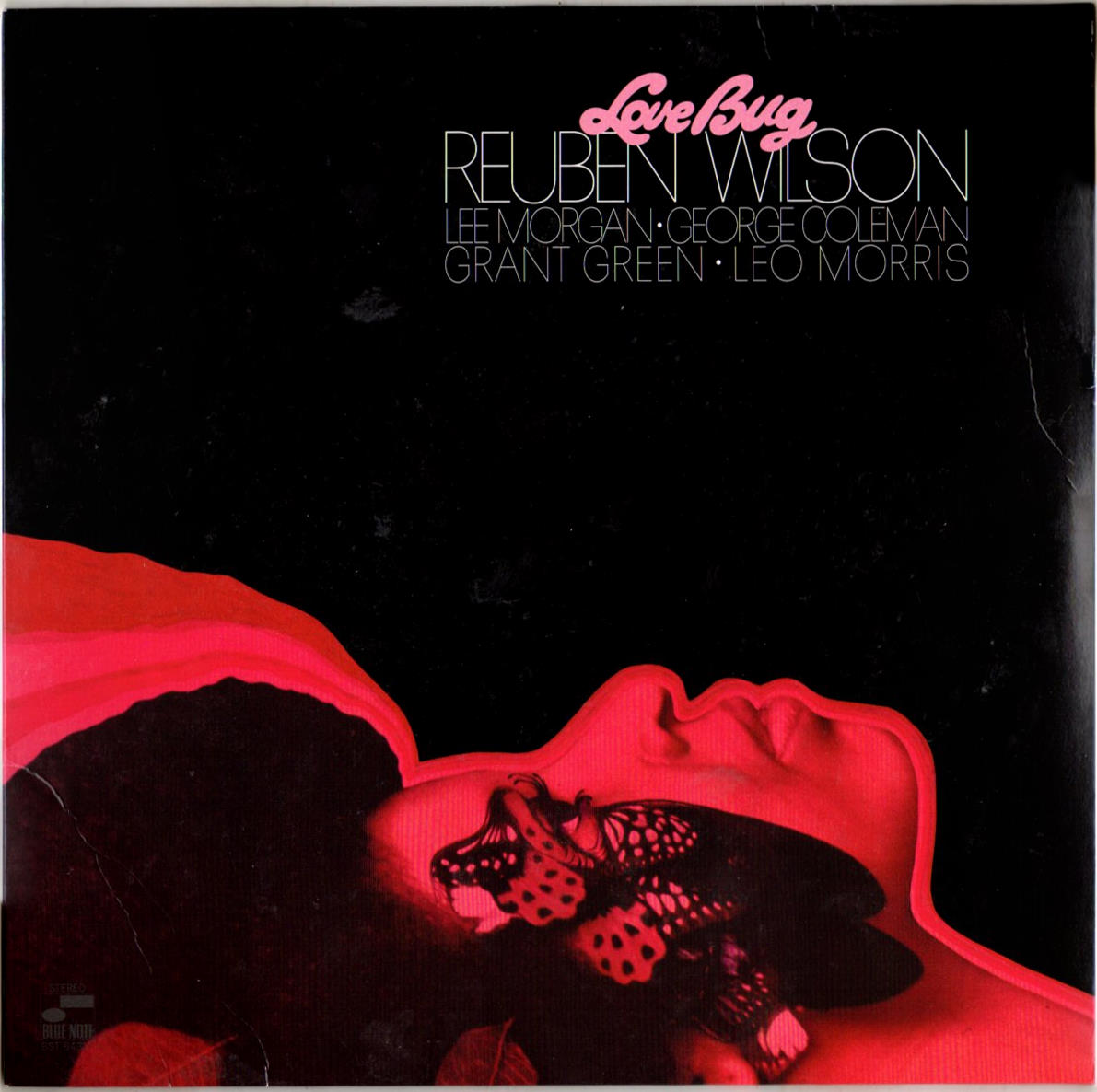

Reuben Wilson’s album, Love Bug, was recorded a little over two months later in March 1969. It’s similar to Turning Point in its instrumental lineup. Lee Morgan and Idris Muhammad are back with George Coleman instead of Maupin on tenor sax. Grant Green, the first call guitarist for bluesy, funky organ sessions, replaces Sparks. The tunes are also a similar mixture of pop and originals. The major difference between the two albums is that Wilson (1935-2023), while a fine player, was not the virtuoso organist and jazz improviser that Smith was.

The album’s first tune, “Hot Rod,” begins with Idris Muhammad’s grooving “your head will shake” bass drum. Like Turning Point, his playing on Love Bug is a creative rhythmic conversation with the soloists while keeping the groove solid and danceable. Wilson takes a long solo that runs through some funky jazz organ rhythm licks, and there are bluesy solos by Green and Coleman, but the show is Muhammad.

“I’m Gonna Make You Love Me,” a hit twice, once for Dionne Warwick and once for the Temptations and the Supremes jointly, is not a tune suited to jazz treatment. Wilson’s arrangement is proto-smooth jazz, probably aimed at radio play. Green plays a typically bluesy solo but can’t seem to do much with the simple melody. Coleman does his best but seems equally stymied. Lee Morgan, like on Turning Point, seems bored or tired, or maybe he just didn’t like organ dates. Wilson doesn’t really try to improvise, and stays close to the melody.

The arrangement of “I Say A Little Prayer” is similarly “smooth,” but the tune is more suited to jazz. George Coleman plays beautifully and wistfully while avoiding sentimentality. Grant Green’s solo is a nice example of his special style of melodic improvisation.

“Love Bug,” a two chord James Brown style funk tune by Wilson, has a very good Coleman solo, but you can sense he’s holding himself back. “It’s an organ date, so don’t play too much.” Green plays his trademark blue and beautiful melodic lines. Wilson’s solo is fine, funky, and very much in the Jimmy Smith mold.

“Stormy,” a pop hit by the Classics IV and far from a songwriting masterpiece, is given another uninspired, easy listening arrangement. The rhythm is so clunky that even Muhammad is at a loss. Everyone seems eager to move on to the next tune.

“Back Out” thankfully returns to soulful groove land. While Muhammad’s irresistible bass drum funk holds it all together, Green and Coleman play blues licks, and Wilson swings hard with some Jimmy Smith boppish runs.

Love Bug is a mediocre jazz album. The soloing is not especially inspired or adventurous. Don’t expect the Lee Morgan of Search For The New Land or the George Coleman of Four And More. But to judge Love Bug as jazz is unfair. It’s really a funky pop/R&B album. The incredible drumming of Idris Muhammad makes it a recommended but not essential purchase for fans of 70s funk/R&B.

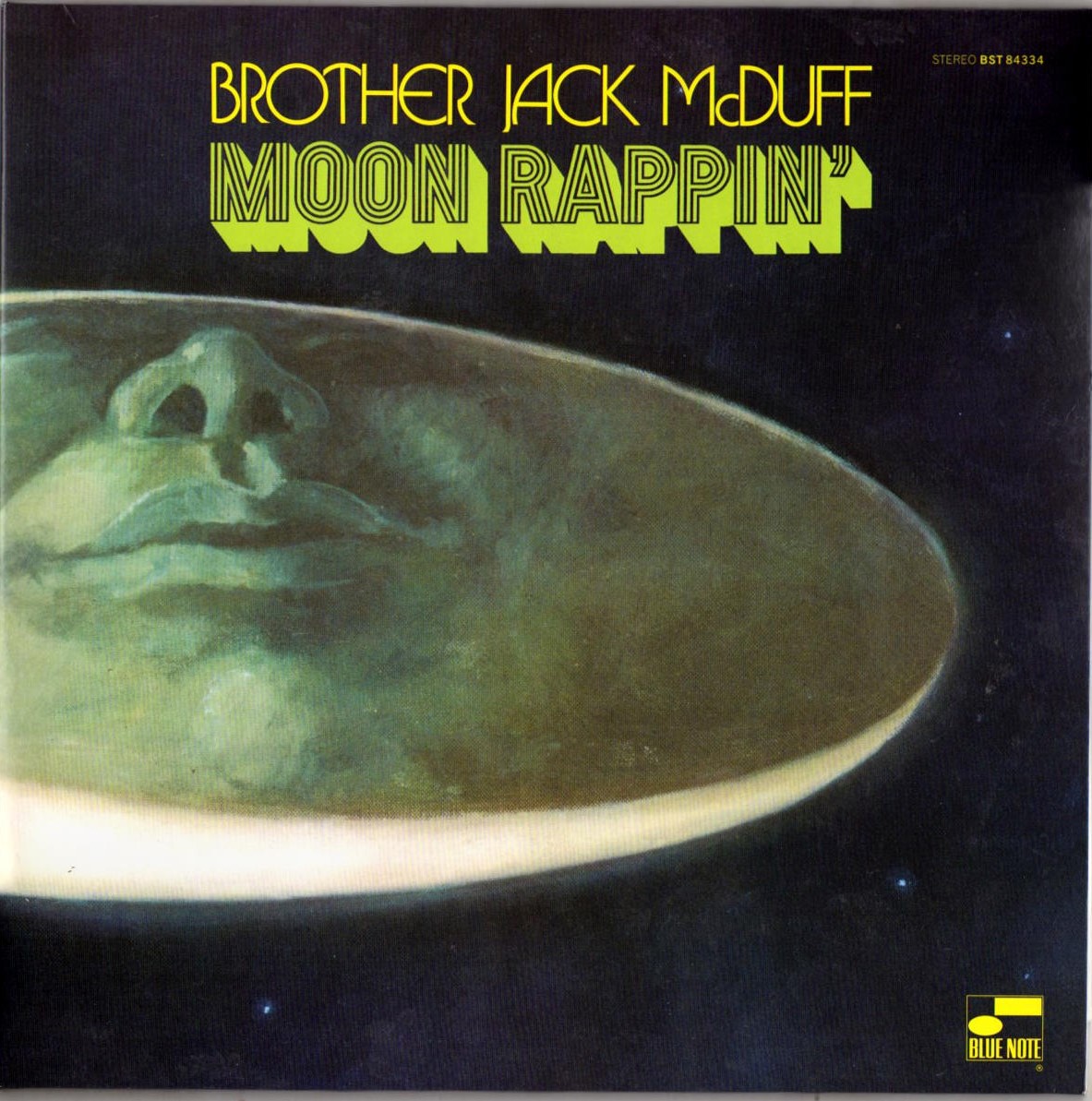

Moon Rappin’ by Brother Jack McDuff was recorded in December 1969 and was a self production. McDuff (1926-2001) was one of the most successful soul/jazz organists following in the footsteps of Jimmy Smith and, in the early to mid-sixties, recorded a long series of albums for Prestige that were very popular with Black record buyers, mixing hard swinging blues with the occasional pretty ballad. The music was jazz, which emphasized the Swing Era virtues of danceability, grooving rhythm, and memorable melody while avoiding any traces of Coleman/Coltrane avant-garde-ism or Miles Davis’ “New Directions.”

McDuff had a keen commercial sense and, in 1968, began incorporating funky guitar and electric bass lines into his music, but it was still music aimed at the older Black audience in jazz clubs, which had been supporting him for nearly a decade. Moon Rappin’ was a “new direction,” an attempt to make a jazz/funk/psychedelic record that would appeal to the hip young Black and white audience that would soon make Bitches Brew a hit. The influence of the R&B chart---The Temptations’ Puzzle People, Isaac Hayes’ Hot Buttered Soul, Sly’s Stand, and James Brown’s Say It Loud-- is obvious.

Equally obvious is that McDuff had spent a lot of time listening to Miles’ In A Silent Way, which had been released a few months prior, and realized that its spacy, open-ended organ/electric guitar, electric bass grooves were not avantgarde weirdness, but a new form of soul/jazz. “Flat Backin’” and “Oblighetto,” the two long tunes that make up the first side of Moon Rappin’, use funkier, tighter versions of those grooves with less harmonically abstract and bluesier soloing over the top. Like In A Silent Way, there are abrupt changes of tempo and theme, and frequently, the only harmonic underpinning is the electric bass, played by the great jazz player Richard Davis. McDuff’s organ solos sometimes venture far beyond his usual soul/jazz style but never lose the groove. There’s a Trane-ish tenor sax solo and even a wordless vocal by Jean DuShon. It’s all held together by Davis’ endlessly inventive, melodic bass and the tighter than tight, righter than right, drumming of the great and underappreciated, Joe Dukes.

Side 2 begins with the title track, a pop style tune reminiscent of those on Donald Byrd’s Fancy Free album, which features a rare McDuff piano solo played over in the pocket guitar, bass, and drums. “Made In Sweden” sounds like a track stitched together in the Miles Davis/Teo Macero manner by tacking the band playing a melody onto the beginning and end of near seven minutes of funky drum soloing and Dukes/McDuff jamming. McDuff’s playing here as far out and wild as Larry Young with the Tony Williams Lifetime. The last track, “Loose Foot,” is a bluesy tune in the jazzy Prestige McDuff style with a swinging tenor sax and organ solos.

Moon Rappin’ is one of the most interesting and adventurous albums in McDuff’s extensive discography and displays an innovative and daring musical intelligence not in evidence on any of his prior albums. The free jazz/funk/psychedelia mixture of Moon Rappin’ is similar to Bitches Brew, but tighter, more focused and lacks Miles’ mysterioso vibe and the amazingly creative soloing. It’s unfortunate that McDuff didn’t explore this style further. Moon Rappin’ is a minor classic that pushes the boundaries of soul/funk/jazz and is recommended to both jazz and funk fans.

Both Turning Point and Love Bug were recorded by Rudy Van Gelder and sound typically excellent. Moon Rappin’ was recorded by Bob Gallo at Soundview Recording. Sound quality is very good with a wide, deep soundstage and lots of dynamic range.

Mastering on all three LPs is by Kevin Gray. Vinyl quality was not up to the level of the more expensive Tone Poet series but quite good.