Britten’s WAR REQUIEM Revisited - A Masterpiece Newly Relevant - PART 1: Genesis and Composition

Decca's 60th Anniversary Restoration and Remastering of one of the catalogue's greatest achievements prompts a re-examination of this profound anti-War statement

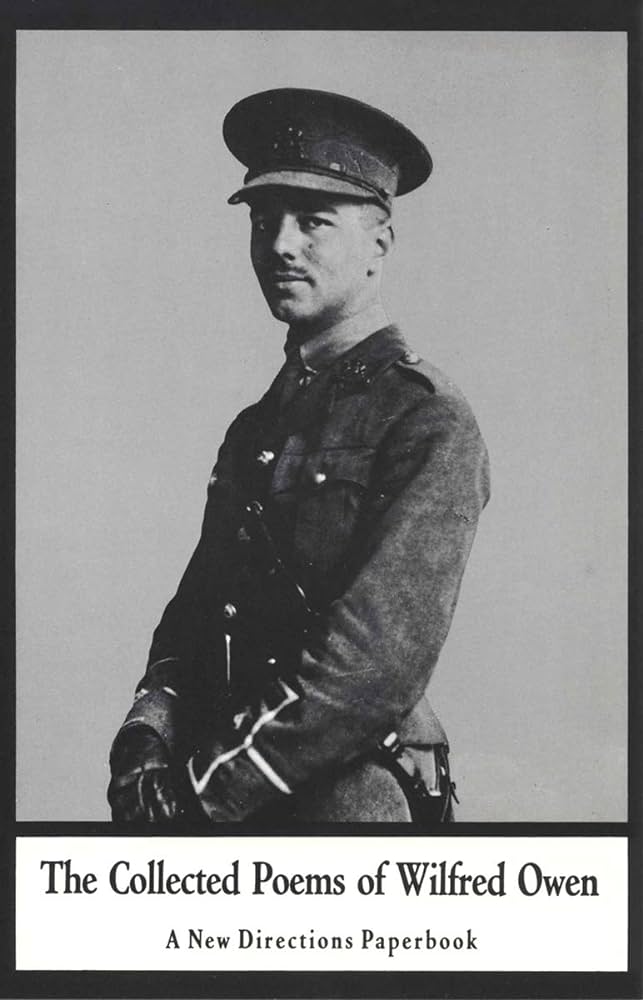

My subject is War, and the pity of War.

The poetry is in the pity.

All a poet can do today is warn.

Wilfred Owen

14th November, 1940.

It was a cloudless moonlit night in the city of Coventry, nestled in the industrial heart of England’s Midlands. The first warning of the attack would have been the sound of the slow approaching thunder of the planes’ engines. The first wave of flare markers lit up the targets for wave upon wave of the bombs that followed. Flames from the fires that consumed the city were visible from hundreds of miles away

The attack, codenamed “Moonlight Sonata”, lasted for 11 hours.

“The dawn was unusual because it came up with a tremendous rose colored light which flooded all over the city for quite a period of time and then disappeared,” recalled one of the raid’s survivors. “I ‘spose the general attitude was the surprise that you were still there when the last bomber went.”

By the time of that bloody dawn over 550 people were dead, over a thousand more injured, and 40,000 homes were damaged or destroyed.

But maybe the most vivid visual testimony to the decimation of the city that night was the crumbled, smoking ruin that had once been St. Michael’s Cathedral, an imposing Gothic edifice dating back to the 14th century.

While the spire and some walls remained standing, most of it lay on the ground in piles of smoking rubble.

There was never any question that the Cathedral would be rebuilt, but in what form. The building was too decimated to be reconstructed to its earlier design (as is being done with Notre-Dame in Paris). In the end, the new Cathedral that emerged over twenty years after that bombing raid found a novel solution to the problem, retaining the old ruins as a garden of remembrance adjoining a new, unabashedly modern building. Designed by Basil Spence, it is considered a masterpiece of mid-20th century British architecture.

But, in addition, the consecration of the new cathedral on 25th May, 1962 was notable for the premiere of a new work specially commissioned for the occasion, by the leading British composer of the time, Benjamin Britten. His War Requiem was immediately hailed as a masterpiece, and its stature has only grown since that time. The subsequent recording by Decca under the composer’s baton is - like the Solti/Wagner Ring cycle - considered a classic of the gramophone, and was also an unlikely bestseller, selling over 200,000 copies within the first five months of release.

For this writer, the War Requiem remains the supreme work of art addressing the folly and calamity of war, unmatched by any similar work in music, art, literature, theatre or film. The resulting recording is therefore significant on so many levels, and, as Europe and beyond once more descend into unspeakable open conflict, listening to these records almost takes on the urgency of a moral obligation.

This is the story of how the War Requiem came into being, its cultural context, how the recording was made, and how these new 60th anniversary vinyl and CD/SACD editions were put together, with a detailed assessment of the sound in relation to the original vinyl release.

Genesis

To understand the significance and impact of the War Requiem you have to understand something of how the British (and other Europeans) related to the wars of the 20th century in the decades that followed, how the experiences and memories of two world wars remained (and remain) in the psyche of the generations that lived through them and came after. It’s a very different relationship to war than that of most Americans, simply by virtue of the proximity of the conflicts. In WWI, a whole generation was more or less wiped out: boys as young as 16 willingly marched to the trenches, where life expectancy could often be a mere few days. During WWII Britain itself was bombed regularly with huge losses of civilian life, and the sheer number of young men and women who lost their lives in combat was considerable. Britain may not have been invaded, but it almost was, and it was always on the front lines. Everyone living in England at the time had some direct experience of the war, and everyone who was too young to fight, or was born in the decades immediately following WWII, met people who had direct experience of both conflicts.

Numbers and names. That was how the two world wars first entered my own consciousness as a young English boy.

I must have been around six, and we were driving across northern France on the way to Switzerland for a family vacation. We were driving across vast, gently rolling farmland. Suddenly I saw them: rows and rows and rows of white rectangular headstones and crosses, as far as the eye could see. My parents explained these were the graves of soldiers who died in WWI and II. Many of the graves were unmarked - tombs for unknown soldiers. No names.

But numbers. Overwhelming numbers of headstones.

Later, aged 13, when I first entered the main quad of my new school, and walked along the corridor into the chapel for my first choir practice, what did I see? Names. Names everywhere. Names on large bronze plaques, names carved into mounted stones - some ornate, some simple. The names of boys from my school who had died, often in their teens, in those same two world wars. It was overwhelming. Endless lists of names. Endless numbers of names.

By then, of course, I was somewhat familiar with the history of those conflicts. I had played with my friends in old bomb shelters scattered around London. In the 1960s there were still some bombed out buildings from the Blitz that had not been reconstructed.

But seeing all those names every day at school, walking by them, sometimes pausing to read them, had an enormous impact. It felt like all that past, all that futile death, was gently nudging at the present, pleading not to be forgotten.

Note the Poppy Wreaths for Remembrance Day

Note the Poppy Wreaths for Remembrance Day

(Years later, when I first visited the Vietnam Memorial in Washington D.C., and descended the ramp to its lowest point, my field of vision filled with the names of those who died, I could not help but be vividly reminded of the hundreds of times I had walked by those walls of names at school. Except that here family members and friends would be touching the names, placing flowers - some weeping, others praying. Children who never could have known their ancestors stood before the wall in silence).

The two World Wars (and the wars since) are remembered in a very tangible way in Britain. Every year there is the Remembrance Day Service, held on the second Sunday of November. In the weeks leading up to the service you will begin seeing little red poppies adorning people’s clothing, bought in support of veterans’ charities. During World War I, when much of France’s countryside became scarred-out battlefields of mud and ruin, the distinctive red poppy was the only flower that would bloom. Thus it became the symbol of remembrance.

During that November Service of Remembrance, and around the country as a whole, there is a two minute silence observed in churches and at the ceremony at the Cenotaph in Whitehall, marking the grave of the unknown soldier, which is attended by the Prime Minister and the Monarch. The silence is followed by a trumpeter playing The Last Post, in memory of all who have fallen.

The Cenotaph in 1920

The Cenotaph in 1920

Singing at many Remembrance Day services growing up remains an indelible, powerful memory. We would often perform the Fauré Requiem, a gentle work of comfort, far removed from the End of Days operatic histrionics of Verdi’s or Berlioz’s quasi-operatic settings of the Mass for the Dead in each of their own Requiem Masses.

Decades later I took my own daughter, aged around 8, to my old school and we attended that same Remembrance Day service. At that time the Iraq conflict was waging, and the sermon was given by an army officer, and many of the older pupils were wearing their cadet uniforms. Sitting in the chapel near to the choir stalls where I had sung my heart out for years, my daughter heard the choir sing that same Fauré Requiem, she heard the same talk of duty and sacrifice, she saw those same names on the walls, and was very still. This was a world apart from her normal everyday life in Los Angeles, where Memorial Day and Veterans Day often pass with barely a mention, let alone much ceremony.

You have to think that back in the 1950s and early 60s, the time of the reconstruction of Coventry Cathedral and the premiere of the War Requiem, the memory of those two world wars was even more vividly present in the minds of the British public, many of whom had been alive for both conflicts. So when it was decided to commission a major choral work from the country’s leading composer to mark the consecration of a new Cathedral standing on the site of the old St. Michael’s, it was of some considerable interest to the public at large.

At that time classical music still occupied a fairly central place in the culture. It was taught in schools, most kids at least sang in a choir, many learned an instrument - or at least dabbled on the recorder! Radio 3 was the BBC’s dedicated classical music channel, every major city had a symphony orchestra (London had, and still has, five), there were numerous music festivals, capped by the BBC Proms, a two-month festival of daily concerts in the Summer, broadcast on the radio, with some being televised.

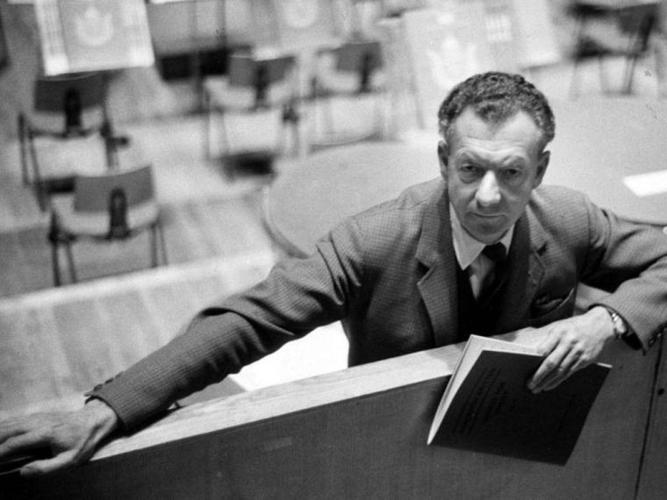

Benjamin Britten

Benjamin Britten

The general public knew who Benjamin Britten was. He had rocketed to national and international fame with his opera Peter Grimes in 1945, and works like A Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra and Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge were performed all the time. Choirs both amateur and professional sang his distinctive choral works. His music was known and loved. It was melodic, tonal, although still modern, but it was accessible. It wasn’t “difficult”, like music of the avant-garde serialists. Britten was a communicator. He famously would opine that he wanted to write music that was useful:

“I believe that the artist... is part of society and he should not lock himself up in an ivory tower. I think he has a duty to play towards his fellow creatures… I want to have my music used. I would rather have my music used than write masterpieces which were not used… I honestly think I can't write in a vacuum. I have to write for people or for occasions”.

So the opportunity to write a work on the largest possible scale at an occasion of national solemnity and remembrance which communicated his profound pacifism was not one that came along every day. He more than rose to the occasion.

Leonard Bernstein once said of Britten’s music that it was seemingly “decorative, positive and charming, and it’s so much more than that. You become aware of something very dark. He was a man at odds with the world in many ways. And he didn’t show it.”

Britten’s discomfort with and within the world was hardly surprising. Ill at ease with his own homosexuality, never a conformer, musically out of step with the avant garde modernists dominating classical composition during his lifetime, he followed his own North Star. This became especially difficult to do early in his life when his deeply felt pacifist convictions found themselves at variance with the mood of Britain as it entered yet another global war in 1939. Already in America as conflict began, Britten and his partner, the tenor Peter Pears, were advised by the British Embassy to remain in the States as Artistic Ambassadors, which they did until 1942, when Britten’s work on Peter Grimes, set in the East Anglian seaside communities near where he had grown up, exerted too strong a pull to resist. Registered as conscientious objectors, fortunately neither had to suffer the indignities of imprisonment like Britten’s slightly older contemporary, Michael Tippett. Soon after the successful premiere of Peter Grimes in 1945, Britten visited Germany with violinist Yehudi Menuhin, performing for concentration camp survivors. The experience further deepened Britten’s pacifism.

Yehudi Menuhin and Benjamin Britten

Yehudi Menuhin and Benjamin Britten

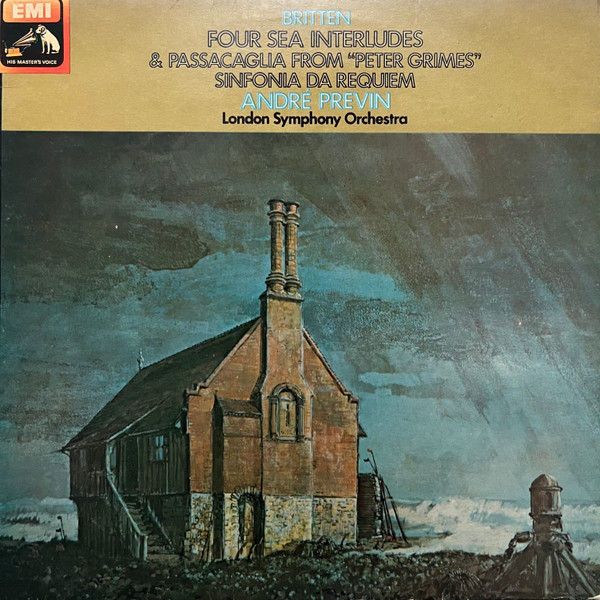

That pacifism had found major expression in an early orchestral work, the Sinfonia da Requiem, composed in 1940 to a most unlikely commission by the Japanese government in celebration of the 2600th Anniversary of the founding of the Japanese Empire. Britten had embarked on the work not fully knowing from whom the commission came. The tangled story as to how the commission unravelled is irrelevant to the work’s formidable power and its pre-echoes of the War Requiem. Given its eventual first performances in America under the batons of John Barbirolli and Serge Koussevitztky, the work not only reveals Britten’s mastery of large orchestral forces, but also his unerring instinct and ability to marry a very personal expressive statement with a public “event” work. As such it is a highly relevant precursor to the War Requiem. (It was the success of this work that led Koussevitzky to offer the opera commission to Britten that led to Peter Grimes).

In the video below from my YouTube channel, you can listen to an extract from the Sinfonia da Requiem as performed on an outstanding EMI record from the 1970s by André Previn and the London Symphony Orchestra (an audiophile classic that should be in every classical music lovers’ library).

The music starts at: 30:02. I make no apology for including one of the most sobering images from the start of the Ukraine War to amplify the agony of Britten’s heart-rending score.

The commission for the War Requiem was one of several for a number of works which would form part of an arts festival celebrating the consecration of the new Coventry Cathedral. Britten’s contemporary Michael Tippett wrote his opera King Priam for the same occasion. But, by virtue of its first performance that was going to take place within the new cathedral itself, all eyes and ears were primarily trained on Britten’s new work.

The Work

Benjamin Britten in Coventry Cathedral during Rehearsals for the War Requiem

Benjamin Britten in Coventry Cathedral during Rehearsals for the War Requiem

One of the immediate attractions for Britten in accepting the commission was the fact that this would allow him to personally commemorate a group of his and Pears’s friends - Roger Burney, Piers Dunkerley, David Gill, and Michael Halliday. Burney and Halliday had perished during WWII; Dunkerley took part in the Normandie landings, and had committed suicide in June 1959, two months before his wedding.

Beyond its significance as a highly personal and also public statement about war itself, every note of the score speaks to Britten’s own strong sentiments of grief at the loss of his friends. An aching awareness of the overarching futility of life - a current that runs through much of Britten’s music - lies at the heart of the War Requiem.

The genius of War Requiem lies in the complete fusion of the personal and the public artistic statement that is the engine driving the score. This is a marriage attempted by composers in numerous musical works, but rarely achieved successfully. (A notable example of such a failure would be Britten’s own opera Gloriana, commissioned to celebrate the ascension to the throne of Queen Elizabeth in 1953, a rare misfire in his oeuvre.)

How does Britten achieve this fusion of the personal and the public statement?

The first stroke of genius was Britten’s decision to construct the work from two distinct threads. On the one hand you have the setting of the traditional Latin Mass for the Dead, which had provided the text for most of the great Requiems composed by Britten’s predecessors (the notable exception being Brahms in his German Requiem, which used for its text passages from the German Lutheran Bible chosen by the composer). The Latin sequences in the War Requiem are set for the main large orchestra and choir, with soprano soloist, and an ancillary boys’ choir accompanied by organ.

The sequences from the Requiem Mass are interspersed with settings of poems by the great WWI poet Wilfred Owen, scored for tenor and baritone soloists and a small chamber orchestra, separate and distinct from the main orchestra. It is the contrast between the incredibly vivid settings of these poems, inspired by Owen’s own battlefield experiences, which are graphic, harrowing but also profoundly contemplative and philosophical in nature, with the supposedly “consoling” text and music of the Latin Mass for the Dead, that gives the work its incredible tension. There is no easy acceptance or consolation in the War Requiem. At every turn one finds oneself questioning the sentiments of the religious texts even as one wants to draw comfort from them.

The poetry of Wilfred Owen, foremost amongst the group of what came to be known as the War Poets, is unflinching in its depiction of both the physical reality of trench warfare, and its emotional and psychological cost. Owen himself died on the battlefield a week before the Armistice was signed.

His poems, inspired by his mentor Siegfried Sassoon, another war poet (and author of the post-War, delightful novel - utterly different in tone - Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man), eschew standard rhyming and structural forms, instead adopting the modernist blank verse idiom. The unflinching examination of the horrors of war in Owen’s poems was in complete contrast to what had hitherto been the dominant, nationalist, jingoistic tone of poets like Rupert Brooke. Brooke’s poem The Soldier epitomized the predominant view of the young men who in 1914 blithely marched off to slaughter:

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there's some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam,

A body of England's, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

etcetera, etcetera…..

Naturally this view was encouraged by the old men and their institutions sending a whole generation of teenagers to their deaths.

Contrast this with one of Owen’s most famous poems, Dulce et Decorum Est (not used in War Requiem) - a poem I had to learn by heart at school (along with the Brooke).

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame, all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin,

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer,

Bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,–

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

(Translation: “Sweet and just it is to die for one’s country”)

Gassed (1919) by John Singer Sargent

Gassed (1919) by John Singer Sargent

The so-called War Poets changed the course of literature. The combination of stark realism, bitter irony, and tragic futility in the face of utter dehumanization and the mechanization of butchery and slaughter was at complete odds with the hitherto prevalent “heroic” strain in war literature. From Owen’s nihilist vision it is but a few short steps to T.S. Eliot’s deconstruction of modern life in The Waste Land (1922). “I will show you fear in a handful of dust” could just have easily been been written by Owen as Eliot.

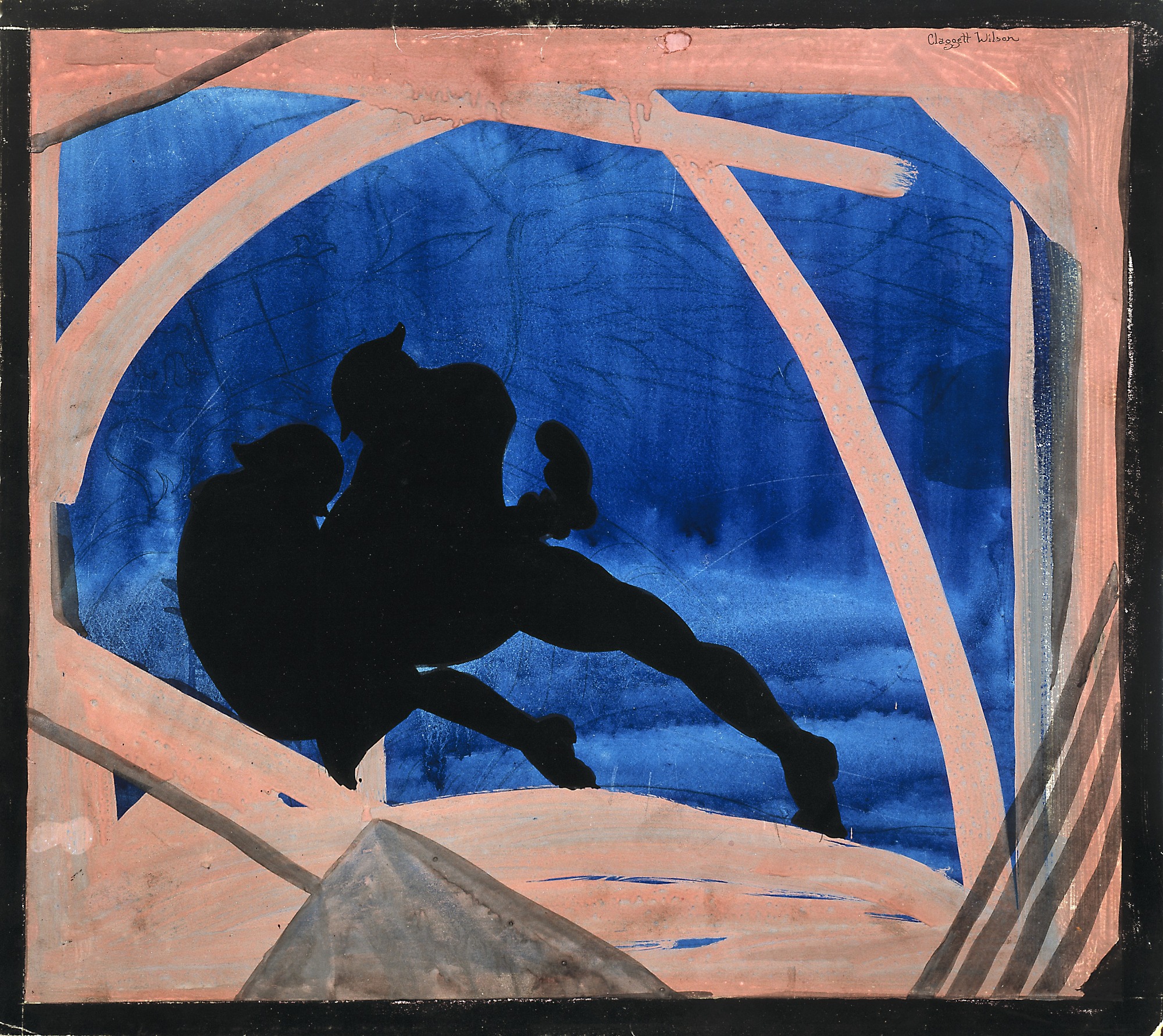

Britten - one of the supreme word-setters in the entire history of music - amplifies Owen’s poems with a vividness and urgency that can make your stomach churn. The tenor and baritone soloists in the War Requiem are the soldiers, living through every ghastly moment of their battlefield lives with a rawness that feels like reportage, not poetry. Yet this is great poetry, and it is great music. The chamber orchestra underlines every nuance, every physical and emotional jolt, binding it to the musical whole. At the very end of the work, after the massive convulsions of Judgment Day in the Libera Me (rendered by Britten in truly apocalyptic fashion), the main orchestra and chorus give way to a setting of Owen’s masterpiece, Strange Meeting. A soldier flees from the battlefield only to meet the enemy soldier he just killed.

Encounter in the Darkness (1919) by Claggett Wilson

Encounter in the Darkness (1919) by Claggett Wilson

Britten’s setting is eerie, terrifying and ultimately welcoming of death as the only rest possible from the battlefield.

It seemed that out of battle I escaped

Down some profound dull tunnel, long since scooped

Through granites which titanic wars had groined.

Yet also there encumbered sleepers groaned,

Too fast in thought or death to be bestirred.

Then, as I probed them, one sprang up, and stared

With piteous recognition in fixed eyes,

Lifting distressful hands, as if to bless.

And by his smile, I knew that sullen hall,—

By his dead smile I knew we stood in Hell……

….“I am the enemy you killed, my friend.

I knew you in this dark: for so you frowned

Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed.

I parried; but my hands were loath and cold.

Let us sleep now. . . .”

At which point the main orchestra, choir, soprano soloist and boys’ choir enter for a vision of the Paradise to come and a final benediction. Or is it?

Even in the final moments of this work, as - for the first time - the tenor and baritone soloists and their chamber orchestra join with the main orchestra, choir, soprano soloist, and the boys’ choir, singing of eternal rest and sleep, a profound ambiguity remains. The music may, on one level, soothe, but does it really resolve the conflict in the human heart - the lust for destruction that so often betrays our better natures and selves, and thwarts our yearnings for concord over discord?

The entire work is built upon, and permeated by, the interval of a tritone - an augmented 4th - labelled as “the devil in music” by the Church during the Middle Ages for its dissonance, and forbidden in compositional practice. This interval opens the work and is sounded again at the very end, before a token final major chord. For Britten, rest and benediction are illusory for humanity - and certainly unattainable for him personally.

(In a sidebar I never thought I would be writing in any context, the tritone is the principal plot point in one of the most recent episodes of the new “Doctor Who” series that just aired: “The Devil's Chord”).

The juxtaposition of Owen’s poetry with the Latin Mass - long the Establishment’s expression of official solace in the face of tragedy and grief - expresses Britten’s profound discomfort with orthodoxy - be it personal or institutional.

The result of this juxtaposition is a questioning of every platitude ever uttered about war. The War Requiem is a sharp, unflinching evocation of the battlefield experience and what it does to the human psyche. It is also a profound meditation on human nature and society’s acceptance of war as a viable means to a questionable aim: victory. Where lies the victory, asks Owen (and Britten), when - in the brilliant rewriting of the parable of Abraham and Isaac featured in the Offertorium - the old man, given the choice by the Angel of God between sacrificing his son to the Glory of the Deity, or sacrificing the ram instead, chooses thus:

“But the old man would not so, but slew his son…

And half the seed of Europe, one by one.”

Parade to War, Allegory (1938) by John Steuart Curry

Parade to War, Allegory (1938) by John Steuart Curry

This work digs deep, questions every moral and societal norm in relation to war, finds few answers, less comfort - and ends up as a profound statement on the human condition in all its messiest aspects. It may be uncomfortable but it is also truthful, and in that truth Britten finds some sense of repose. The work is also an urgent warning, a call to end the cycle of nation state aggression and retribution. As we watch what is happening right now in the Middle East and Ukraine, the truth at the heart of the War Requiem burns like a hot poker pressed into one’s eyes.

The work has never felt more relevant than now.

Symphony of Terror (1919) by Claggett Wilson

Symphony of Terror (1919) by Claggett Wilson

In the video below, from my YouTube channel, you can listen to one of the most powerful passages in the work, where the culminating Libera Me climaxes into the beginning of Strange Meeting. The passage begins at 24:30, and the accompanying visuals are drawn from paintings by WWI and WWII artists.

Coming up in Part 2, the story of how the War Requiem was recorded by Decca’s crack team of producer John Culshaw and engineer Kenneth Wilkinson, and became a major event in the history of the gramophone.